The Map Is the Territory

A project by Mathcastles foregrounds not only the code behind virtual worlds but also the collective imagination and effort that are required to flesh them out.

At Nagel Draxler’s Crypto Kiosk in Berlin, a new exhibition by Sarah Friend titled “Terraforming” brings together recent works addressing the aesthetics and practices of mining, as well as the physical presence of blockchain technology and the behaviors of its users. (After several pop-up appearances, the Crypto Kiosk opened earlier this year as the blue-chip gallery’s dedicated space for NFT-related exhibitions.) Friend is already well-established for her thought-provoking work with blockchains and NFTs. Her Lifeforms (2021) is one of the most conceptually sophisticated NFT projects to date. Its titular formations develop over time but “die” if they are not transferred. Through the medium of the smart contract, Friend deploys the culture of infinite exchange licensed by the blockchain while also lampooning its “grindset” excesses. “Terraforming,” on view through December 17, sees Friend working in a somewhat different way, treating blockchains as a subject matter rather than a medium.

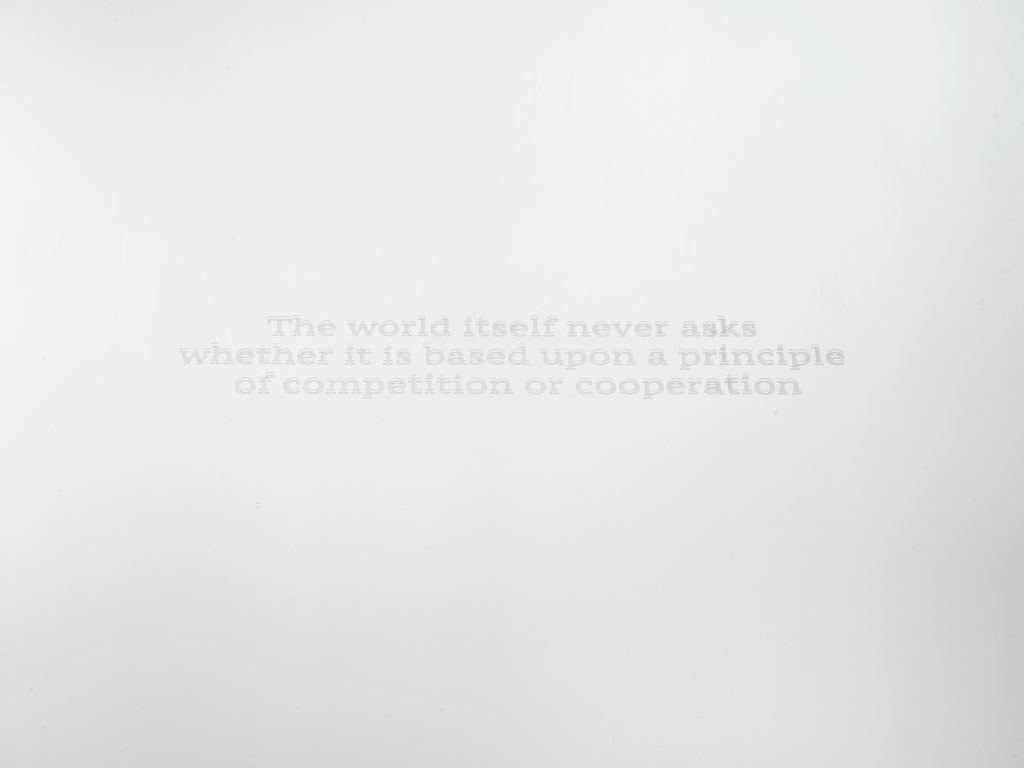

Entering the Crypto Kiosk, the viewer is greeted by Threshold (all works 2022), a mirrored floor piece inscribed with a koan-like phrase from Masanobu Fukuoka’s 1975 natural farming polemic The One-Straw Revolution: “The world itself never asks whether it is based upon a principle of competition or cooperation.” It is an intriguing introduction to an exhibition that takes the relationship between these two apparently opposing principles as its central theme. Friend was inspired by the political scientist Robert Axelrod, whose 1984 book The Evolution of Cooperation sets out the argument that cooperative behaviors can in fact emerge in competitive environments. For the artist, the mechanisms of blockchain mining are a useful example of this thesis. But with Threshold Friend also seems to be making an epistemic point, asking the visitor to recognize the futility of attempting to bend the world to fit into frameworks with which the human mind is comfortable. While the “world itself” may be indifferent to our efforts to understand it, it has responded to our efforts to dominate it, as the blockchain community is all too aware. The recent Merge, Ethereum’s change of protocol that dramatically reduced its energy consumption, took place two days before the opening of Friend’s exhibition.

The video As Above So Below catalogues the major data centers of Berlin, drawing the viewer into the weird ecology of data brokers, server farmers, shell companies, and investment funds that make it up the infrastructure of the internet. The data centers are where the ostensibly dematerialized and distributed blockchain lives. In materializing these spaces, Friend’s video, ironically, is “powered”—a term used to mean “underwritten” or “supported”—by Google Earth. The company permitted Friend to use imagery created with the platform in exchange for the waiver of certain prerogatives, including the right to commercial gain. This dynamic of accessibility and control is a key theme of the video. Friend’s narration traverses Berlin and Marburg, moving from one nondescript-looking office complex to another as she traces the intermingling of German state power and data sequestration. Here was a forced labor camp. Here was a secret police headquarters.

Are the internet’s infrastructures of secrecy and enclosure also digging the grave of human freedom, one search term at a time?

Today, of course, nobody here is (directly) forcing their employees to work, but a free democracy is far from the top priority of companies seeking to enclose as much data as possible for commercial purposes. In her narration, Friend poses the question of how the internet can transcend the “ruins”—forced labor, displacement, all-encompassing surveillance—on which it is built. That is a profound, if perhaps unanswerable, question. Another one: What can be done about the ruins the internet is building? Are these infrastructures of secrecy and enclosure also digging the grave of human freedom, one search term at a time?

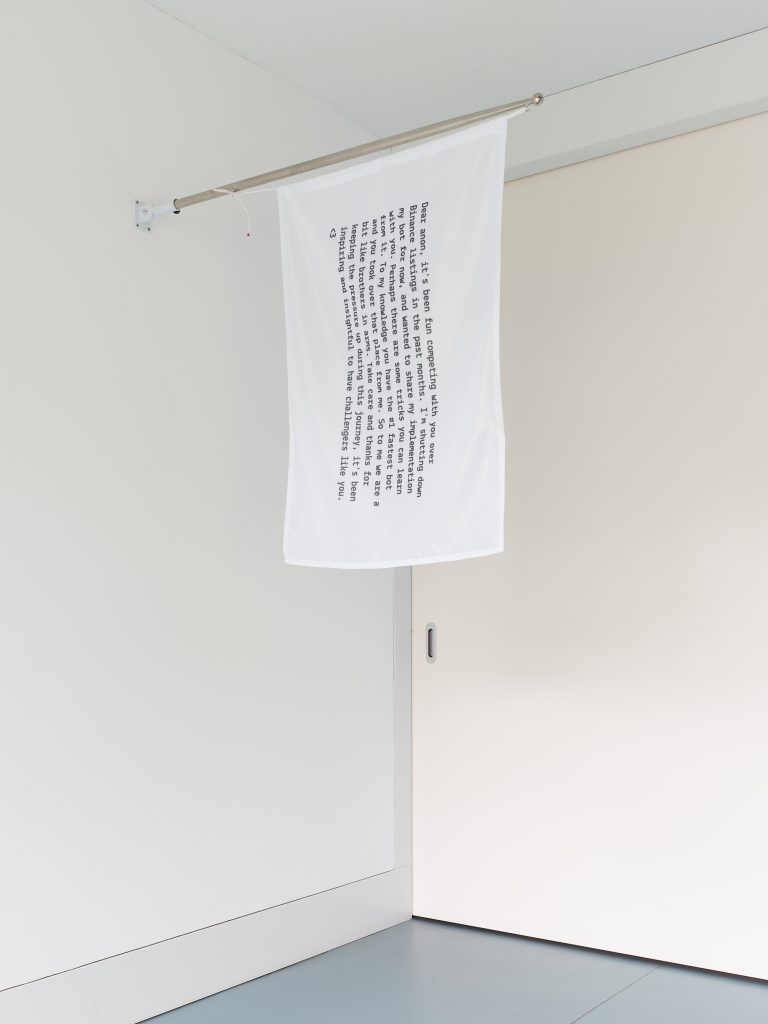

The video is displayed on the floor of the Crypto Kiosk, facing the ceiling. Above the screen from poles mounted on the gallery’s south wall hang two banners printed with text. Returning to the idea of competition and cooperation, White Flags commemorates a kind of digital Fashoda Incident between two blockchain miners seeking to outrun their competitors by exploiting the infrastructure of the system, in a process known as “maximum value extraction” (it’s been described as an invisible tax, and also compared to insider trading). The flags are printed with the final messages of the miners to each other. One reads as a kind of concession to a rival whose bot proved superior: “Take care and thanks for keeping the pressure up during this journey.” The other is a challenge, concluding: “No matter how long it takes I will wait for you in my strongest form. Until that day you must hone your abilities. Then seek me out and surpass me.” An exhibition essay from Nagel Draxler describes this exchange as “collegial” and “almost poetic” but for this non-miner the lines had more of the ring of Dragon Ball Z, or some kind of battle of anime adversaries—even the ravings of a supervillain: Meet me in the blockchain, Mr. Bond!

Will the movement toward dencentralized autonomy transcend the ruins upon which it is built?

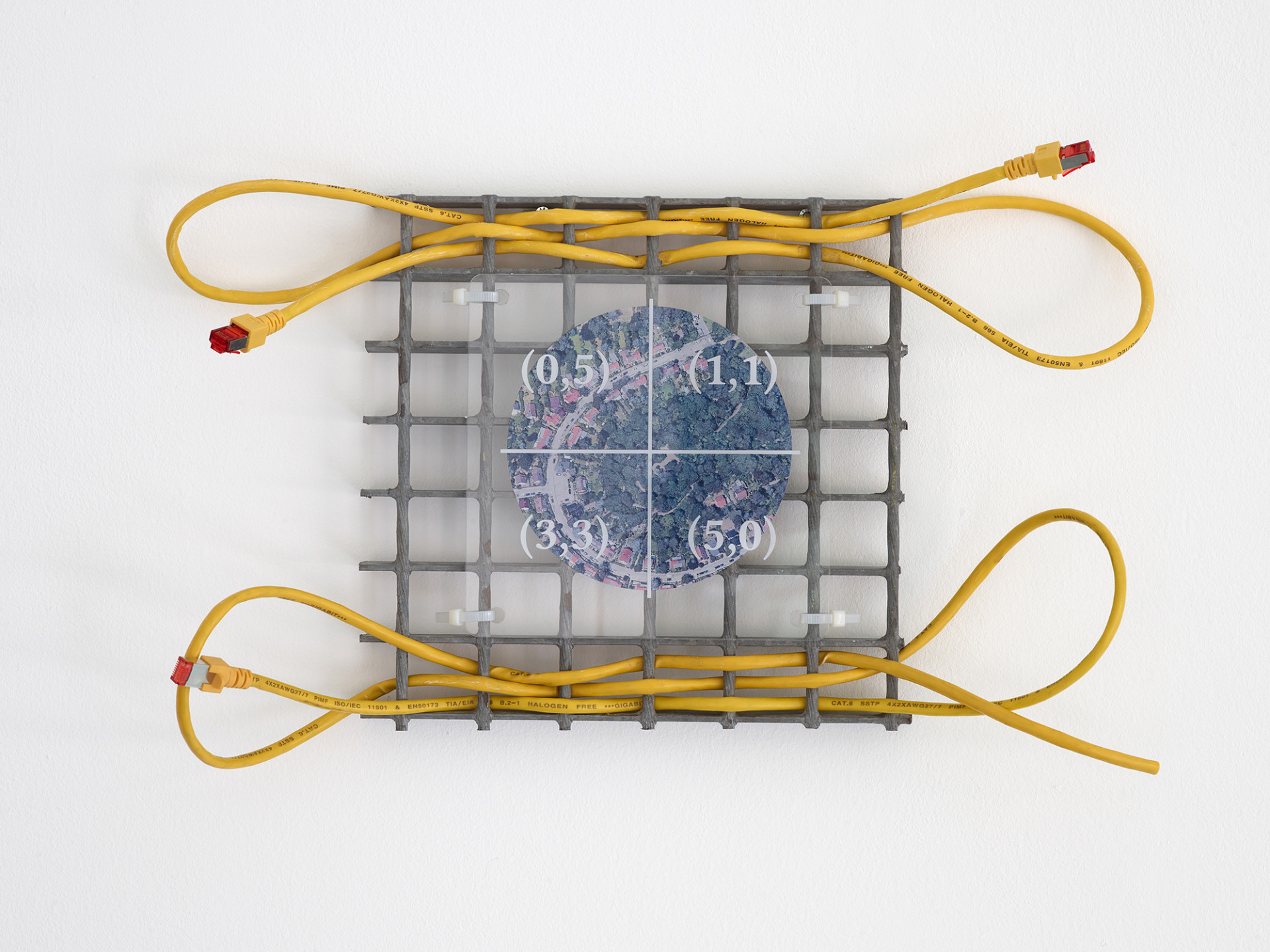

Throughout the exhibition, Friend makes the most of the physical space of the Crypto Kiosk to explore the material realities that lie behind blockchain technology. In works such as Shadow of the Future, a schematic of the time-spaced continuum printed on glass and set over an air filter, she repurposes discarded materials found in data centers. Perhaps the most impactful installation is a small dispenser of earplugs at the right-hand entrance to the space. Workers at data centers use them to protect their hearing from whirring servers. Here, though, they seem to have a dual meaning; the dampening of sensory input evokes the wilful ignorance of many a pre-crash crypto bull. Friend’s processes of selection and re-presentation function like an archaeology of the present. There is something ominous to this premature museification. Will the movement toward decentralized autonomy transcend the ruins upon which it is built? Or will it only create more ruins?

William Kherbek is a writer living in Berlin. Entropia, a volume of his collected art writing, was published this year by Abstract Supply.