The Hirsch Truth: Episode 3

Why are digital artists afraid of raunch? Ann looks at CryptoDickbutts and listens to fart NFTs.

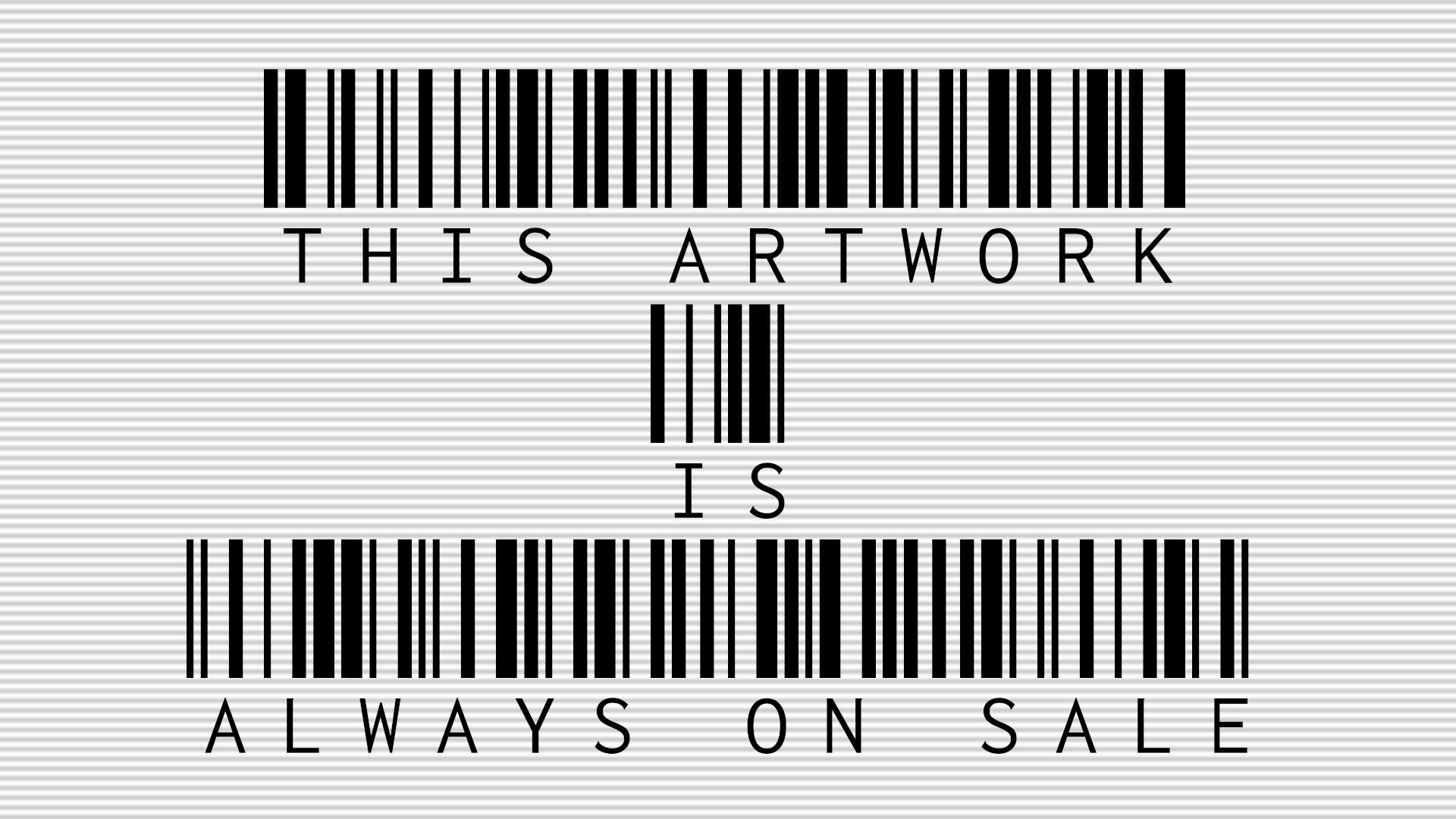

Simon de la Rouviere is many things, including a full stack developer, a metaverse content creator, the author of a cyberpunk novel, an avid blogger, and a researcher whose work has been influential for crypto commons discourse. He is also an artist, and his NFT project This Artwork Is Always On Sale (2019) was longlisted for the 2022 Lumen Prize NFT award. As one might hope, This Artwork Is Always On Sale does exactly what it says. The NFT, which points to a black-and-white digital image showing a barcode graphic and an all-caps inscription of the work’s title, features a simple smart contract functionality with complex implications: the project creates perpetual royalty income for the artist while also keeping the artwork in circulation at a reasonable price. When you buy the piece, you must set a non-negotiable price at which you are willing to resell, and on the basis of which you will transfer an annual five percent royalty fee to the artist for as long as This Artwork Is Always On Sale remains in your possession. If you desperately want to keep this work forever, you could choose to assess it at an extremely high value—let’s say 1,000,000 ETH. Nobody would then be likely to buy it off you, but of course this would also result in a staggering 50,000 ETH annual royalty fee. Failure to transfer the fee would trigger a self-enforcing “foreclosure” protocol that returns the work to the artist. If, by contrast, you don’t want to pay much in royalties, you could set the work’s value near nil, say 0.01 ETH. This would make it extremely cheap to own, but also extremely likely that someone will come along and snatch it away.

With its combined royalty and forced-sale functionality, This Artwork Is Always on Sale is a fascinating experiment in recalibrating artists’ control over how they solicit support for their practice. In making this work, de la Rouviere adapted an unorthodox property tax model known as Harberger Tax, or Common Ownership Self-assessed Tax (COST). The model compels the owner of a property to set the price at which they are willing to sell it, and to pay an annual property tax on the basis of this self-assessed value. For de la Rouviere, the Harberger Tax model has worked out well. At the time of writing, This Artwork Is Always On Sale exists in two versions. The first is valued at 5 ETH, and has earned its creator roughly 31.35 ETH in royalty fees; the second, which was created in 2020 and stipulates a 100 percent annual royalty fee, is currently valued at 1 ETH, and has earned the artist some 12 ETH in royalties. So far so good! In adapting the Harberger Tax, however, de la Rouviere glosses over some inherent contradictions of benevolent market capitalism, ignoring key differences between social welfare and benefits to individual artists, as well as between competitive markets and the commons.

De la Rouviere’s system takes a model intended to support the public and turns it into a model that creates a private revenue stream.

Eric A. Posner and E. Glen Weyl proposed the Harberger Tax in their 2017 article “Property Is Only Another Name for Monopoly.” They developed their model with three specific types of property in mind: real estate, corporate shares, and the radio spectrum. In their view, it is in the public’s interest for these types of property to remain available for purchase at any time. This, they argue, will foster competition and enable the kind of productivity that economists like to describe as societal welfare gains. Withholding such properties from circulation, for example for speculative investment purposes, can create monopolies that impede the productive use of resources. The Harberger Tax model penalizes this by making monopolization prohibitively expensive.

In a Medium post, de la Rouviere praises the system’s ability to calibrate a balance between “pure private ownership and total commons ownership in order to increase general welfare to society.” It’s not difficult to see why such a balance might inspire an artist to design a new pricing mechanism and royalty scheme. What argument could possibly be made against a reliable revenue stream for artists? To highlight these benefits, de la Rouviere positions his mechanism as a radically new type of patronage. In an artist statement for This Artwork Is Always On Sale, he notes that the system serves several important goals: artists receive royalties in perpetuity, speculation is disincentivized, artworks don’t disappear in vaults, and digital art ownership becomes more accessible.

But de la Rouviere’s vision relies on some semantic slippage. To begin with, patronage is not comparable to taxation. Taxes are levied by government, and represent a compulsory contribution to state revenue, intended to support things like housing, education, and healthcare. Patronage, by contrast, is given by choice, usually to support individual artists or collectives. So, by definition, patronage is not a tax, even when a particular patronage model adopts mechanisms of taxation. We may agree that a strong royalty system can benefit society at large because it engenders a healthy and vibrant art scene. But strictly speaking de la Rouviere’s system does not operate to the benefit of a larger art community. Instead, it takes a model intended to support the public and turns it into a model that creates a private revenue stream (in perpetuity, no less). Here, an additional problem appears: if there is one thing that most crypto pundits can agree on, it’s probably that they just don’t like compulsory regulatory fees collected on behalf of states or state-like institutions—i.e., taxes. In more ways than one, blockchain technology was invented precisely on the basis of this dislike. This sentiment will not change if the label patronage is applied to the concept of taxation.

We also have to consider whether an art object such as a digital image can be treated as analogous to the property types to which Harberger Tax was originally applied. Is a work of NFT art “like” a piece of real estate? If economic productivity is the goal, it certainly makes sense to incentivize public access to real estate or to the radio spectrum. I’m not convinced that the same is true for NFTs, or for artworks more generally. Yes, the public benefits when art is made accessible for all—for instance, in public institutions such as museums. But de la Rouviere’s patronage system does not reimagine art as a public good, which would make it non-rivalrous and non-excludable—free to access, use, and share. What it proposes is that the artwork should always remain accessible on the art market as a commodity (though not as a speculative asset), and that owners should be taxed in order to create a private revenue stream for artists. As Posner and Weyl say of the Harberger Tax, this “amplifies the operation of the market economy rather than curtailing it.” In other words, de la Rouviere’s patronage model has nothing to do with creating an art commons. Rather, it’s about designing a specific type of market regulation that incentivizes engagement. In this sense, the Harberger Tax model will appeal to web3 proponents and their ideals of empowering users by monetizing participation.

If there is one thing that most crypto pundits can agree on, it’s probably that they just don’t like compulsory regulatory fees collected on behalf of states or state-like institutions.

The tokenized digital art milieu is still heavily characterized by a taste for financialized transaction. I think it’s no exaggeration to say that for many web3 evangelists, NFTs wouldn’t be worth owning if not for their speculative qualities as financialized assets—but that is precisely what Harberger Tax penalizes. Sure, it’s nice when a profitable trade also supports an artist, but the cynic in me doubts that this is widely seen as a main reason for buying, owning, and selling NFT art. Despite all the hyped rhetoric around blockchain art OGs and their artistic genius, the way in which NFT art circulates online suggests, sadly, that it’s mostly about the assets. We can see this attitude reflected in the recent trend for some NFT marketplaces to abandon equitable royalty schemes in order to make trading more attractive (read: profitable) for users. Certainly, such a trend amplifies the need for a functioning patronage system. It does not suggest, however, that the art market will readily embrace it.

Nevertheless, the proposition at the heart of de la Rouviere’s This Artwork Is Always On Sale is very worthwhile: let’s curtail the speculative element of digital artworks, let’s make artworks more accessible, and let’s enforce a sustainable royalties system for artists. Yes, let’s! But how?

Implemented on-chain, the Harberger Tax model can easily lend itself to additional fine-tuning. At the very least, the model could therefore be used as a tool to collect information about the “background noise” of art-market dynamics and collector preferences. If the Harberger Tax is set to almost nothing, it will favor collectors who want to pump the value of their portfolio; if it is cranked all the way up, it will attract those who mainly want to support artists. But is there a sweet spot, a percentage that stimulates communities of artists and collectors to self-organize in the most productive way? With some experimentation, it should be possible to identify the most widely accepted percentage fee that collectors will be happy to accept, and thereby define a best-practice royalty scheme.

Is there a sweet spot, a percentage that stimulates communities of artists and collectors to self-organize in the most productive way?

Just as intended, de la Rouviere’s project points directly at a fine line between what the artist calls “pure private ownership” and “total commons ownership.” In my view, a solid royalty system and the disincentivization of speculation are precisely what the digital art world needs. But some key questions remain to be answered. What exactly is the general welfare to society that de la Rouviere’s adapted model is meant to create? There must be more, surely, than repackaging taxation as patronage. What if, for example, in a new version of The Artwork Is Always On Sale, the project’s smart contract functionality were to be recalibrated so that the royalty fee is allocated to causes that really do benefit the public? Or what if a distributed consensus element was added, to involve a larger group of fractional co-owners in deciding how patronage fees should be allocated and used?

For now, perhaps we have to imagine a different context for implementing such a model. If the competitive art market resists anything akin to tax regulation, then maybe the domain of DAOs will be more amenable to it. After all, it is here that the affordances of blockchain technologies are frequently used to explore new forms of co-ownership, collective stewardship, and commitment to commonly agreed rules. In the closed-loop patronage relationship between artist and collectors proposed by de la Rouviere, there is not yet a “society” that could benefit from a property tax model. DAOs, by contrast, are built around communities with shared interests and goals, and it is to such communities that self-assessed taxation and forced sale functionality of the Harberger Tax model might ultimately appeal.

Martin Zeilinger is senior lecturer in computational arts and technology at Abertay University in Dundee, Scotland.