The Emperor’s New Clothes

Digital garments have been heralded as a revolution for sustainability in the fashion industry. But are they mainly just a cash grab for big-name brands?

Decentralization is a fundamental principle of web3. Blockchains were invented so that currencies could circulate outside state or corporate control. What does this mean for the art world? How are decentralized systems changing the way art is funded, produced, collected, and displayed? Which of these changes have been made practically possible by new technologies versus those which are more theoretically influenced by the ethos of decentralization? And what are the real benefits and potential roadblocks of operating in this way? As part of Outland’s collaboration with guest editor Refraction DAO, we spoke with six artists and art professionals about their perspectives on decentralized curation. Each brought their own specific experiences to bear—as founders and members of DAOs, as artists, as curators, and as entrepreneurs. Running throughout their contributions was a heartening conviction in the potential for decentralization, despite its challenges, to help create a better and fairer art world for everyone involved.

Decentralization is a state of being in which action requires multiple independent actors to reach consensus on said action. A DAO is simply an organization that requires its members to reach that consensus. Often we think of “real DAOs” as having that mandate embedded in code, but I think the actual hard part of having an organization is getting members to care enough to participate in consensus-building, whether on-chain or off.

I don’t think it’s important for everyone to take a decentralized approach to curatorial projects—if that was the case, I’m not sure any actual curating would ever get done. But I do think it’s extremely important for decentralized approaches and projects to exist. Practically speaking, the space is so new, so distributed, and has so few barriers to entry that an incredible amount of work has been produced, and it’s impossible for any one person to have a deep understanding of it all at this point. Leveraging the hivemind can be beneficial in this regard. Ideologically speaking, I think it’s important to continue imagining and experimenting with the new structures that verifiable decentralization can provide, rather than simply utilizing existing technological and social patterns.

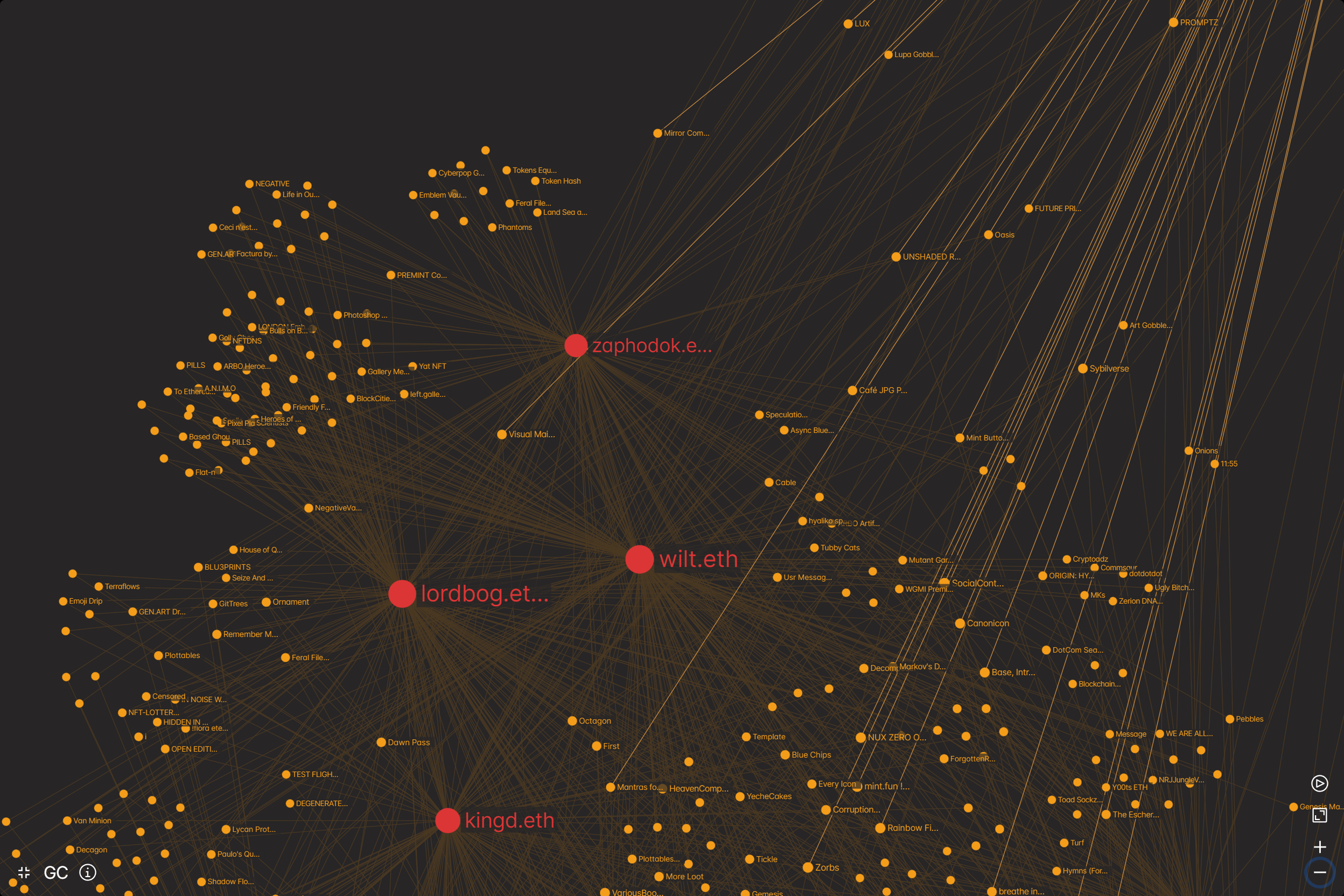

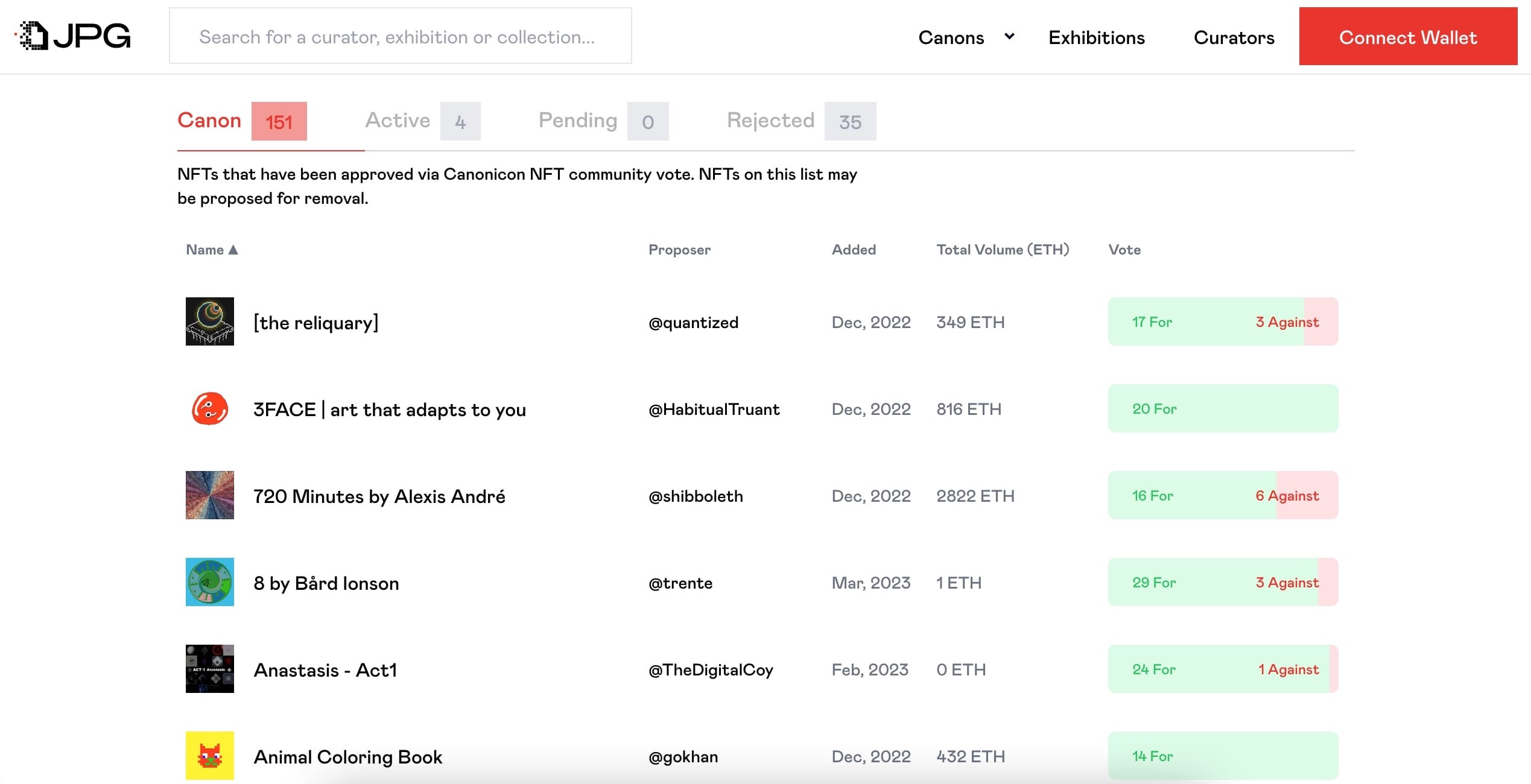

JPG is a great example of the hivemind approach, as the community proposes and votes on NFT collections to be added to various Canons—a mostly tongue-in-cheek name for categorical lists of NFTs. So far we have seven canons—these include Dynamic, Conceptual, Cryptosocial, and Derivative—each of which highlights an interesting area of the NFT space. These feel like the first of many verticals within NFTs that need to be indexed, and there is currently no other source for such information. It’s been an extremely productive process so far, and we have fifty or so committed members of the community consistently researching, discussing, and voting on proposals.

I view our approach so far as more of a curatorial starting point than an end result. It’s the first step of mapping the landscape. We’re able to create these new sources of data and research because we’re sourcing information from a wide swath of people, including artists, collectors, and curators. Proposers get to show off their knowledge and expertise while voters get to learn and discover new things. Compared to the algorithmic indexing that will probably eventually come to the space, our approach may seem a little messy and unsophisticated. But so much of the excitement of what we’re doing is in the conversations sparked by the Canons. It’s definitely produced some of the most stimulating discussions about NFTs I’ve experienced in the past three years.

In 2018, Penny Rafferty collaborated on research into the Berlin art scene which showed that the elevating of a select few artists by museums, venues, funders and patrons often left art-worker communities in a poor condition. This work led to the Black Swan whitepaper, which proposed a new arrangement in which established art-world players, such as venues, galleries and collectors, become “silent stakeholders” in a city’s art ecosystem. They pledge resources—funds, exhibition space, commissions, materials and mentorship—to the DAO, whose member community of artists, curators and researchers then decide, in a system of proposals and voting, how they will use the resources.

At Furtherfield, we’ve also been working since 2018 on a project called CultureStake, a collective cultural decision-making app. This was our first attempt to make a technical build that made sense for the community based around our gallery in Finsbury Park in north London. It uses quadratic voting on the blockchain, which allows people to express not only their preferences but the intensity of their preferences. That helps us explore the feelings attached to the choices that people make about what they want in places that they value. Although not strictly a DAO, CultureStake does work around the decision-making element of a DAO. It has a strong focus on location, which has always felt very important to us. So many art DAOs take the internet as their world. Furtherfield is in a public park and we feel a responsibility to the place.

Black Swan DAO was prototyped as part of five years of art-world DAO labs, think tanks, prototyping events and summits that Furtherfield and I led with Penny with Goethe Institut-London and the Serpentine R&D Platform. This built a network of thinkers and practitioners with a critical perspective, and culminated in our book Radical Friends: Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Arts (2022).

We’re now using the Black Swan DAO model as the basis for the Translocal Artworld DAO, to distribute the model developed in Berlin to five cities around the world. For two years we’ll have an umbrella organization, where the stewards of each of the city DAOs can share knowledge and shape peer-built cultural infrastructure. Together we’ll work out what is good for us all and what is good for particular ecosystems. The project is as much about creating communities that suit local needs and ensuring that art workers make decisions about what those needs are as it is about sharing knowledge across different cultures.

For me the word “decentralization” means the decentralization of power. In traditional artistic structures, this power is held by those who continue to produce and reproduce hegemonic thought. As a nonbinary person and a Brazilian artist, I think it is important to question and rethink these structures so that we can include a larger and more diverse number of voices in our space.

Before getting involved web3 I was already undertaking curatorial and research projects, with the intention of promoting access for artists in my home country—always focused on the party scene and transdisciplinary artists. Then I came across the Mint Fund, a community-run initiative which onboards BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists from all over the world by helping them mint NFTs. Since then I’ve been involved with Magma DAO, a collective of Brazilian artists, and we’ve also collaborated with Refraction DAO.

Both Magma and Refraction have their roots in nightlife and electronic music. This world has shaped the way I see life and produce my art, so when I and my friends in Magma saw what Refraction was doing, it made immediate sense. I believe that nightlife provides a safe bubble for artists around the world. Parties and sites of celebration offer an effervescent space of creativity.

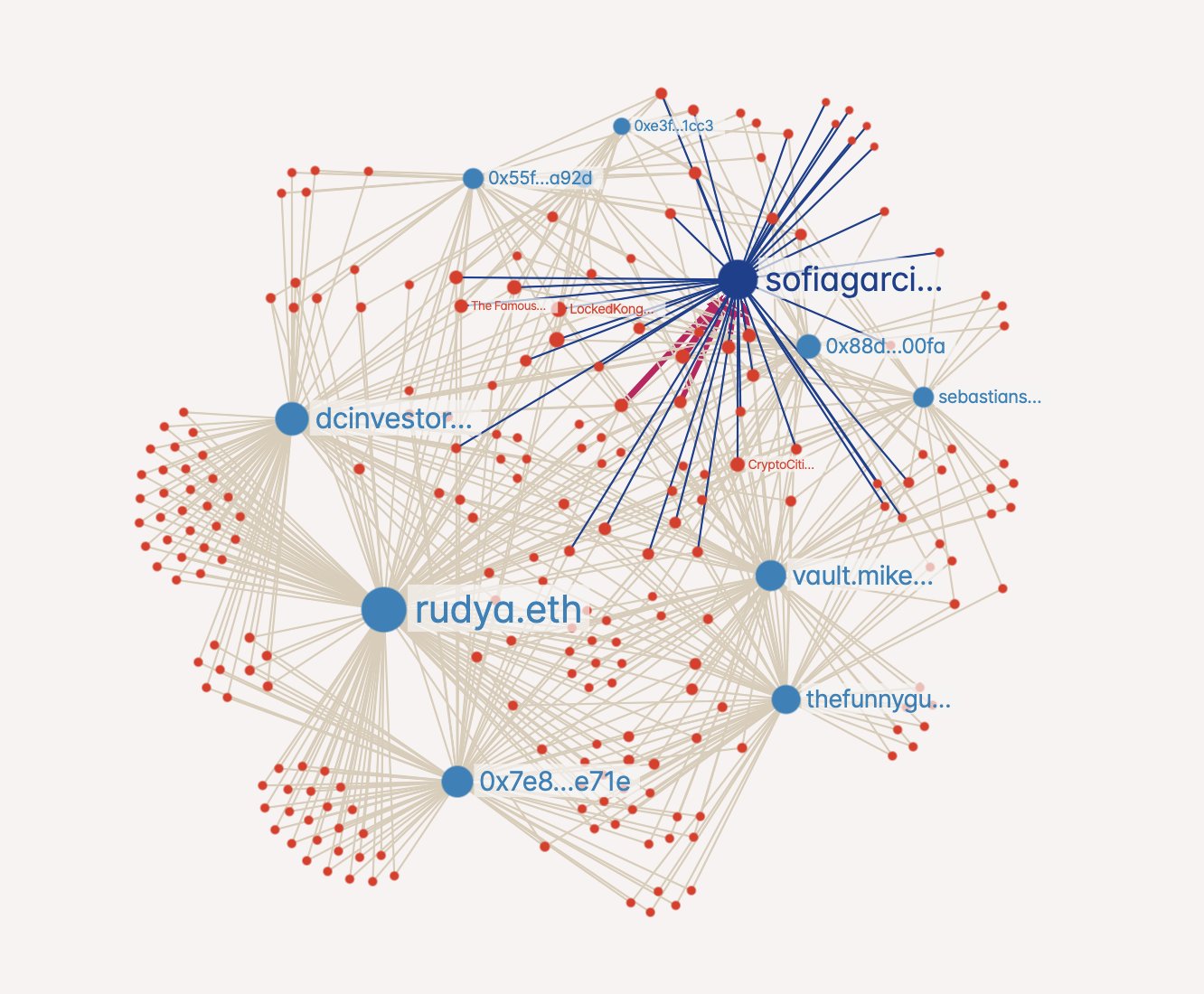

An artist familiar with both the traditional art world and the NFT space might describe them as parallel universes because of their unique coordination infrastructure, i.e., how value is transferred and records are maintained. Yet the role of networks in both is strikingly similar. My experience with galleries, museums, and biennials led me to question the forces underpinning art institutions. In 2011, I began mapping networks of artists, curators, and (starting in 2013) collectors, uncovering hidden cliques, central and peripheral players, and bridges between clusters. These maps exposed invisible institutional frameworks.

In the NFT space, the artist controls the value transfer, and parties are coordinated around common protocols, with verifiable public records. But similar social dynamics are present. The information about who collects from whom remains as influential as it was in the 1990s when Saatchi “discovered” the YBAs. Social Contracts, created for a project commissioned by JPG, map connections among NFT collections. They highlight the interpersonal dynamics of the NFT market, and predict collectors’ future acquisitions. The project is based on McKenzie Wark’s theory of art as a derivative that functions as a “portfolio of simulation values,” meaning representations and reputations matter more than the work itself. Minting a Social Contract generates a personalized graph that evolves over time, reflecting the collector’s interactions and acquisitions within the NFT ecosystem. Each piece is a derivative of its owner’s collection graph. When a Social Contracts NFT is transferred or sold, the artwork is recomposed, blending the new owner’s data and its provenance. The work therefore presents new economic and aesthetic feedback loops, challenging the conventional patterns of art collecting. To me, decentralized curation means communities making decisions about art in coordination with a protocol. I created Social Contracts as an artwork, and like my other works, it is not an object, but a system. However, network maps in general are indeed valuable tools for curating knowledge and art.

When we first conceived of Gemma, we were both reading The Hour of the Star, a 1977 book by Clarice Lispector that opens: “All the world began with a yes.” This phrase kept coming up in our discussions, as a reminder that all creative acts—from making a painting to coding an algorithm—begin with a commitment from a creator to take the first step. How do we help creators advance beyond that blank page to create something meaningful? We believe the answer lies in making that experience more connective, supportive, and collaborative.

Gemma is a new culture fund that operates collectively, with decision-making power spread across the organization. Feminist principles have inspired our approach to organizational and governance design, which means prioritizing intersectionality over either/or thinking, and collective decision-making over individualism. Our first release is Mantras for Artists, which takes the approach of Oblique Strategies (the 1975 card deck devised by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt) for inspiring creativity with a randomized selection of prompts. It incorporates our core symbol, the upside-down triangle. To us, this shape represents the inversion of top-down power structures, as well the crucial role that supporting structures and networks play in culture and society.

We believe that arts funding organizations need to evolve in order to reflect the values of our generation. We want to see more opportunities for community participation and influence, both in terms of who’s invited to apply for funding, and who makes decisions about how funds are allocated. We also want to see into the guts of how an organization functions, so that decision-making is more transparent and equitable. Overall, we want to see artists involved in this process because our ultimate goal is to attribute value back to those who create it.

As we grow, Gemma will be a group of tastemakers and visionaries who are invested in funding, supporting, and providing context around the most important artists and artworks of our time. If the web3 era is about decentralization and financialization, then our collective task is to critique, challenge, and expand upon what that means.

At the end of last year I curated “DYOR,” an exhibition of crypto art, at Kunsthalle Zürich. To curate in a world whose principal ideal is decentralization involves a certain contradiction because curation demands selection, exclusion, and gatekeeping. Most people would, I think, accept that we need filter systems or curators who have done their research, and who can identify works and contextualize them thoughtfully. The question is “how?”

For “DYOR” the solution was to involve as many artists, curators, collectors, visitors, and even traditional galleries as possible to ensure diversification, decentralization, and inclusion. The exhibition was therefore structured according to several subsections managed by different creators. There was also a strong emphasis on projects that invite participation. For instance, with Silvio Lorusso and Sebastian Schmieg’s project A Slice of the Pie we were able to create an ongoing and ever-expanding exhibition. For the duration of the exhibition, an LED wall displayed a circular pie-like shape divided into six slices. A dedicated website livestreamed the pie 24/7. Via the website, artists were able to purchase one or more slices and fill them with their own artworks, thus becoming full participants in the exhibition. During the exhibition, more than 120 named artists (and many others who remain anonymous) joined the initial list of some 150 participants.

I see the biggest challenge facing DAO-like structures as finding a balance between the need for defined roles and responsibilities in terms of effectiveness, and the advantages of network-like systems. On the plus side, you get community involvement and support, participation, inclusion, diversity, access to a broad pool of creative talents, workload sharing, and speed— “DYOR” was built within a couple of months.