Manual Override

In the work of Tyler Hobbs, the relationship between humans and machines is filled with productive tensions.

The 180 iterations of CryptoGodKing (2021), Steve Pikelny’s first project on Art Blocks, stylize the omniscient pyramid seen on the dollar bill and combine it with hypnotic patterns of concentric circles and triangles. It’s a blunt, psychedelic riff on the cultish aspects of money. In an interview on CryptoGateway, Pikelny points out that religion and currency alike depend on faith, whether in the existence of God or in the acceptance of money as payment. “People form all sorts of emotional connections to these things, and even build their lives around them,” he says. CryptoGodKing connects this phenomenon to NFTs: “even though we’re essentially just flipping bits, people build these elaborate social and personal narratives around what it means to ‘own’ a token, and they derive real-world, non-digital joy from that.”

Pikelny gave CryptoGateway two more interviews about his subsequent Art Blocks releases, Fake Internet Money (2021)and Maps of Nothing (2022), which, as the unnamed reporter points out, both deal in abstractions without referents—images of money and maps that don’t stand for real systems of value or real places. “You took the words right out of my mouth,” Pikelny replies. They have a great rapport. I came across these interviews last summer, when I wanted to learn about how Pikelny took up the speculative dynamics of NFTs to explore questions of value and desire. As I read, my interest in Pikelny got eclipsed by my curiosity about CryptoGateway. Such good content on NFT art—why hadn’t I heard of it before? I clicked around the header menu—ART, INTERVIEWS, DEFI—but the links didn’t take me anywhere. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realize that the site was a fake, something Pikelny had thrown together to release information about his work in a way that conferred the sense of importance that comes with interest from the press. From this false publicity to the work itself, where connections between meanings and appearances are severed, and even to the faith-based assertion that owning an NFT means owning an artwork, Pikelny’s work juggles interlocking systems of lies and beliefs. He operates in the social spaces of art and crypto where people conspire to make meaning from nothing. He traces the scams that take place in those spaces, and launches “scams” of his own.

It wouldn’t be fair to call Pikelny a scammer—he winks hard enough about his tricks to give them away to anyone paying more than glancing attention, and often he says what’s going on outright. (I initially missed the line on his web page that says CryptoGateway is a fake site he made, and the line at the end of the CryptoGodKings interview about how he “built this entirely fake crypto art website just so I could publish a fake interview with myself to make it seem as if I had more artistic credibility.”) By flirting with hoaxes, Pikelny is larping as a run-of-the-mill NFT huckster. He’s also continuing a venerable tradition of conceptual art. Joseph Kosuth generated interest in his early work by publishing reviews of it that he wrote himself, under the name Arthur H. Rose. “Modern and contemporary art rely as much on hype and celebrity as they do on creativity and innovation,” writes art historian Christopher Howard in The Jean Freeman Gallery Does Not Exist, a 2018 book about an artist who placed real ads for shows at a fictional gallery in art magazines in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Now that conceptual art holds a stable position in art history, it’s easy to overlook the promotional efforts artists undertook to cultivate faith in the value of their slight, cerebral gestures. I cite these precedents not to confer some sort of art historical legitimacy on Pikelny’s work, but rather to demonstrate what they have in common: artists fascinated by the possibilities of what can happen within the magic circle of art, and by the work of persuasion it takes to establish that circle.

Religion and currency alike depend on faith, whether in the existence of God or in the acceptance of money as payment.

Before he got into crypto, Pikelny made art about the proliferation of conspiratorial narratives that prey on the lonely and gullible. His 2016 website Fake Bullshit News uses the flashing, boldface urgency of the right-wing aggregators to present texts pulled from real and fake news sites and garbled by an algorithm he wrote himself. Seven years after the project’s launch, its automated reporters continue to work, pumping out articles on CIA investigations, gun control legislation, and Trump’s tussles with the press. Pikelny is still exploring the aesthetics of online scams; his net art piece Terminally Online (2022) renders slogans from clickbait ads as full webpages, using primitive html tags like marquee and blink to animate the text in bland voids.

Pikelny took an interest in crypto during the ICO boom of 2017, and released his own coin via the website FastCashMoneyPlus.Biz early in 2018, where it’s hawked with clashing neon colors, egregious pop-ups, and the requisite legal disclaimers. A follow-up project, Not a Security (2018), is “a wealth-redistribution utility token”: proceeds from new sales are divvied up among early holders. This is Pikelny’s stab at coding a pyramid scheme on the blockchain, and it’s presented without the flash of Fake Bullshit News and FastCashMoneyPlus.biz, perhaps out of discretion (advertising pyramid schemes is against the law). But like those earlier projects, the presentation of Not a Security explores vernacular design—the way things look when put together by people who have something to say but not the patience or funds to hire a professional. Here, Pikelny imitates the crypto whitepaper, with columns of plain text and a few graphs drily explaining the token’s mechanics. Not a Security is abbreviated as NOT, and the capitals of this false acronym pepper the whitepaper with phantom double negatives, making it hard to parse assertions and denials amid all the equivocation about NOT’s legality.

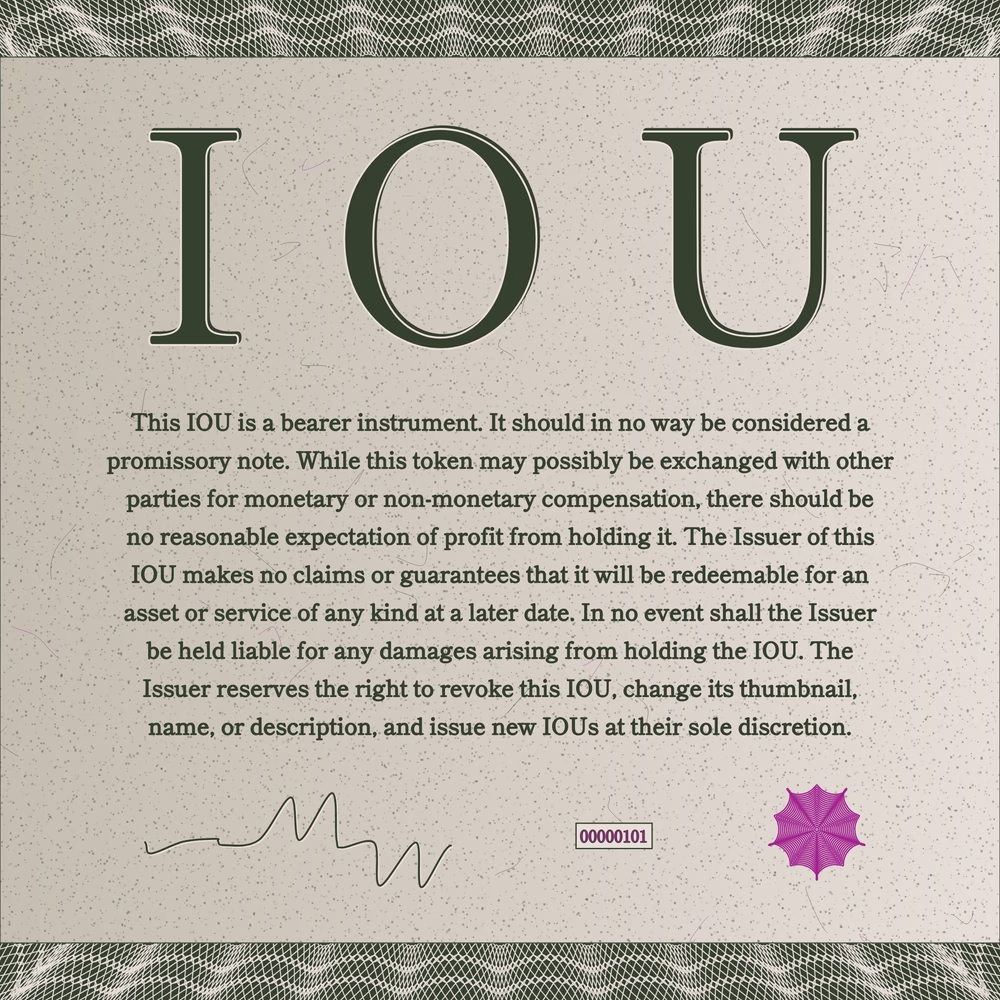

Pikelny relishes the comedy of this deadpan confrontation between crypto’s promise to create value from the mysterious workings of the blockchain and the conscientious attempts not to promise too much. IOU token (2021) “may possibly be exchanged with other parties for monetary or non-monetary compensation, [but] there should be no reasonable expectation of profit from holding it.” Imagine Coin (2021) “can be whatever you want it to be. It can be a conceptual art piece, a meme coin, a radical anarchist social experiment. And while it might be difficult to exchange Imagine Coin for reality-based coins, you are free to imagine a wild profit-making future for yourself.” Pikelny’s dance of disavowal reached an apogee with Instructions for Defacement (2022), which debuted during the Art Blocks Open House in Marfa last November. Collectors (myself included) lined up to purchase an NFT that came with a set of instructions for a plotter to produce a random selection of designs and shapes on an area equal to that of a dollar bill. But since defacing currency is a federal crime, Pikelny and Plottables (his partner, a platform which uses the minting mechanics of Art Blocks to generate instructions for plotter drawings) distanced themselves from straightforwardly encouraging collectors to use their NFTs to mark up money. Prospective collectors had to sign a thick legal document before purchasing the NFT and receiving a one dollar rebate, in cash—which, for the most part, they eagerly took to a table nearby where plotter pens and computers stood ready to do crime. The instructions produce arrows, moustaches and penises on George Washington’s face, lacy figures illuminating the guilloche pattern on the bill’s background, and other designs inspired by the doodles most commonly found on circulating bills. Like Fake Internet Money—a collection that reconfigured the aspects of banknotes that make them collectible, from serial numbers to misprints—Instructions for Defacement alludes to the idiosyncratic ways in which people find meaning in money beyond the value guaranteed by fiat, and standardizes them with an absurd algorithmic logic.

Pikelny’s work alludes to the idiosyncratic ways in which people find meaning in money beyond the value guaranteed by fiat, and standardizes them with an absurd algorithmic logic.

While Pikelny has issued prints of some of his digital artworks, Instructions for Defacement is the only one to date that involves a physical manifestation from the outset. And yet the project hinges on Pikelny distancing himself from the authorship of those objects. For Sol LeWitt, the work was the instructions, not the drawing. This is true of Instructions for Defacement as well. But in this case it’s not just an assertion of the centrality of the concept—it’s also a legal necessity. The work twists together the technical languages of code, law, and conceptual art in a simple, funny gesture.

Pikelny has leaned into the metaphysical aspect of generative art elsewhere. The description of CryptoGodKing on Art Blocks says the work “cannot be owned, but each unique incarnation may belong to a cryptographic soul of the Ethereal realm.” Kosuth reviewed his work under a fake name, but in 1969 under his real name he published an influential essay titled “Art after Philosophy,” where he argued that in the twentieth century religion and philosophy lost their power, and art fulfills the spiritual need left in their wake beyond by making assertions beyond that which can be scientifically measured. The work of Kosuth and his peers exuded a kind of Protestant austerity, inviting solemn meditation on the philosophical conundrums they presented. Pikelny’s work addresses a need for fulfillment, too, but he recognizes how spiritual yearning can commingle with the base, desperate hunger to get rich quick.

While Kosuth often included dictionary definitions in his work to set a tone of disinterested authority, Pikelny likes to speak in voices that are interested and biased, even when they wade into the neutral register of the whitepaper or legal disclaimer. He highlights this tension to give his audience permission to laugh. Being in on the joke is another feeling of belonging: Pikelny’s work actively addresses us, urging people to buy in. The old conceptual art could be aloof because it operated in the dignified realm of exhibitions and magazines, but Pikelny’s work exists in online networks, Discord and Twitter, where the connection to the audience is immediate, and it manifests as tokens, ERC-20 or ERC-721, to be collected by many. The social shapes and effects of the scam were a means to an end for the old conceptual art, ways of generating hype and awareness. But for Pikelny these are mediums to be explored; they’re where the art happens.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.