Exonemo

The collectability of NFTs is a new conceptual playground for an artist duo that for two decades has explored emotional connections to digital media.

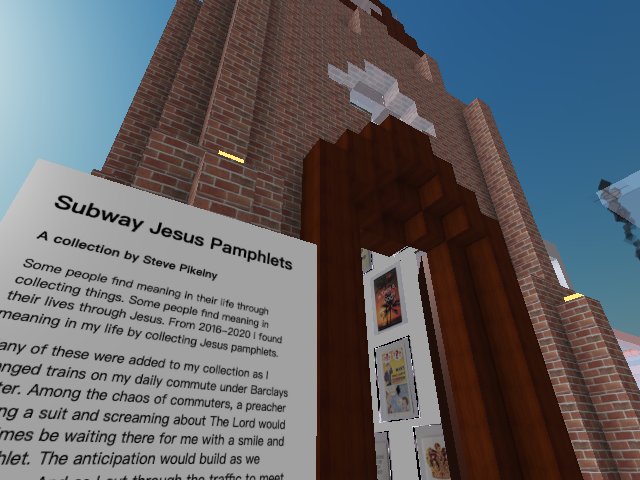

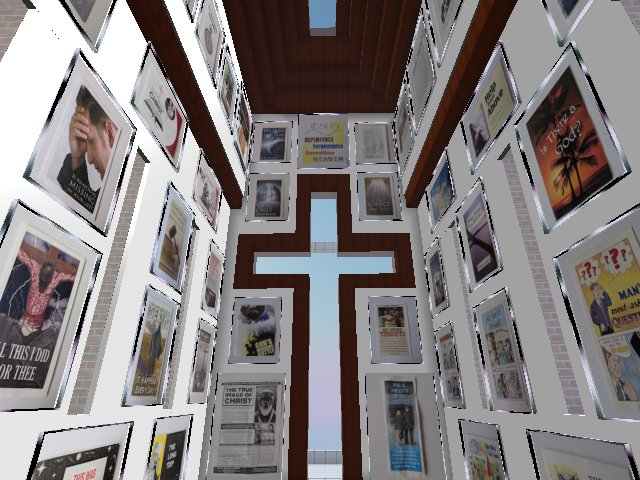

What does an art collection in the metaverse look like? Wander through a virtual world, and you’ll probably encounter some white cube space with jpegs decorating the walls, or maybe a garden of 3D sculptures and floating videos. Artist Steve Pikelny took an unconventional route to creating a metaverse gallery. He built a virtual church to showcase NFTs minted from the religious pamphlets he’d collected on his IRL commute: the Church of Subway Jesus Pamphlets, in the San Francisco district of the Voxels metaverse. Pikelny’s work deals with systems of belief, including art, religion, and finance, and shows how the faithful are vulnerable to scams. His pamphlet collection is one avenue through which he explores those ideas, and the Church in Voxels is a way to share it. Pikelny spoke to Outland about how the collection came about, what it means to transpose relics of everyday life into a virtual environment, and what that implies about similarities between Christianity and crypto.

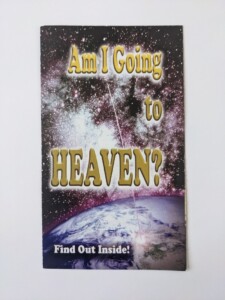

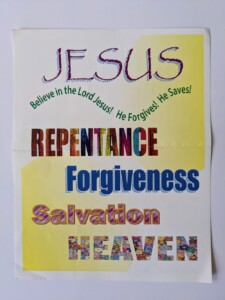

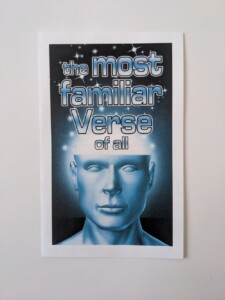

In high school I was handed a Jesus pamphlet on the subway and, being an angsty atheist teenager, I thought it was funny. When I moved back to New York in 2016, I continued collecting these pamphlets during my daily commute. My co-workers joined in and gave me the ones they picked up on their commutes. They called me the “Jesus Pamphlet Guy.” Before I knew it, I had amassed a collection of fifty Jesus pamphlets.

In 2021 I got into the idea of digital collectibles, and I had a lot of ideas for NFT projects. I started thinking about weird things I’d collected in real life, like the Jesus pamphlets. I thought it would be cool to translate this collection into the digital world. So I photographed each pamphlet in my collection to show that they are physical objects. It was important to me that these were photographs and not scans, as I wanted to emphasize that I own physical copies, not just the PDF versions that the publishers of these pamphlets often put online. The act of taking a picture gave it a different feel: I was documenting a physical thing.

Initially, I thought of it as a big project. I bought a plot in Voxels and spent a lot of time building a church in the San Francisco District to use as a gallery space. I created metadata for the pamphlet photos and listed them all on OpenSea at 0.05 ETH. People complimented me on the collection, but no one bought anything. After I released CryptoGodKing (2021),my first project on Art Blocks, I made the Jesus pamphlets into reward tokens—I’d give one to anyone who bought a CryptoGodKing. I gave maybe fifteen or twenty of them out that way. A few months later the market started heating up and I was shitposting about the CryptoGodKing collectionon Twitter. A few influencers who caught wind immediately started shilling it, and all the remaining tokens for that project sold out in a few hours, without the incentive of a free gift. Since then, I’ve been giving the Subway Jesus pamphlets away as Christmas presents, even though I’m Jewish and don’t celebrate the holiday.

Before I focused on the Church of Subway Jesus Pamphlets, I used my Voxels plot to mess around. I made the Stevie P Gallery, doing what a lot of people do in Voxels: I showcased my art collection with multiple levels and a nice view of the ocean. I also created an I Saw It in a Dream (2021)installation with a bunch of test mints displayed in an interesting way. In general, I’m a fan of Voxels and enjoy bumming around and seeing what others are doing.

A lot of people view crypto assets as similar to real estate because they promote speculative behavior, where you buy and hold onto an asset with the hope of its value increasing. Metaverses like Voxels highlight this behavior even more, as they create a digital space that resembles physical real estate. People buy plots of land in Voxels and don’t do anything with it besides speculate on its value, similar to what happened when cities were growing very quickly in the early twentieth century: people bought plots of land and held onto it in hopes of the price going up. The creators of Voxels structured the land so that the value of plots depends on their location in relation to each other. They’ve simulated space and traveling and the time it takes to move through the space.

I also collect pamphlets from New Age and other spiritual movements. They remind me of my interest in pyramid schemes and how people delude themselves. The art on them often tells stories about protecting yourself against electromagnetic frequencies or engaging in past life therapies. Some pamphlets are not interesting, but many of them are fascinating and transport you to a different world. Still, when you go through the pamphlet you realize it’s just someone trying to sell a weird product and shake you down for money.

One of the things that influenced my creation of CryptoGodKing was reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011). It’s one of my all-time favorite books. Graeber was an economic anthropologist who studied how pre-industrial societies organized themselves politically and economically. In Debt he discusses things that seem like NFTs but are physical. They’re objects treated as valuable and sacred, even though they may not have much material value. This resonated with me when thinking about NFTs and the social construction of value around them.

I was already in a headspace where I was considering the creation of immaterial value through faith and religion. With CryptoGodKing, I wanted to explore the idea of collectibles and how to create value for something that normally wouldn’t be thought of as a collectible. With the pamphlets, the connection to Jesus and religion added another layer of interest, as it presents the idea of the artifact having spiritual significance. Someone handing you this object in the subway almost feels like it has the power to save you, even though it’s a financial artifact.

—As told to Brian Droitcour