Gaming the System

Mitchell F. Chan’s digital works combine conceptual art strategies and computer games to show that play can be serious business—and vice versa.

In 2006, Ariel Pink released an album, Thrash and Burn, with a photo of the artist Jill Miller on the cover. Miller had never met the musician or consented to the use of the image. This past January, she released her response, Ariel Stinks (50 Alternative Album Covers to Thrash and Burn), on the NFT platform Taex. Feeding prompts into an AI image generator, and then digitally editing the outputs, she crafted fifty album cover replacements. Now Pink appears stinkily—on the toilet, as a used car salesman, in the guise of a skunk. Miller offers a free downloadable paper album cover, a book of all fifty images, and a series of NFTs each priced at 500 USD. One stated aim is for Pink to buy them all: to compensate Miller for using the photo of her, but also so that he will never again have to waste his time on another album cover. At the AMP San Francisco art fair last month, she set up a “Record Cover Swap,” inviting owners of Pink’s records to swap the original covers for signed copies of Miller’s versions.

While much discourse surrounding NFTs focuses on economic value and legal rights such as ownership and copyright, Miller has explained that her project “intentionally sidesteps litigation”—she is not interested in confrontation. “[Pink is] a self-proclaimed contrarian. He’s starting from a place of agitation and disagreement,” she said. And his malfeasance only bloated under Trump. He attended the “Stop the Steal” rally on January 6, 2021, and made an appearance on Tucker Carlson to whine about how this had cost him a record label and tour. (Around the same time, a former partner’s allegations that he had abused her were also made public.) Miller, a socially engaged feminist artist, wanted to respond to him in a way that reflected her own ideas about justice: reparations rather than revenge.

Ever to be associated with Pink through his illicit face-grab, Miller’s project reactivates but also perhaps begins to repair their disharmonious relations. “Making all those album covers, I would just die of laughter,” she said. With levity and joy, Ariel Stinks engages Pink directly—but on Miller’s terms as an artist.

Alexandra Juhasz is distinguished professor of film at Brooklyn College.

Julian Opie’s early digital drawings “Imagine you are walking” (1993)—blank streetscapes seen from eye level, blocks of color forming the walls, ground, and sky—encourage viewers to place themselves in a digitally constructed wasteland and populate it with their imagination. This project later became a series of computer-generated walkthrough videos that resemble a spartan version of the Windows 98 3D Maze screensaver. OP.VR.01 (2022), an immersive VR installation on view last month at Lisson Gallery in London, seeks to realize this techno-utopian promise of endless possibility in the virtual world by placing the viewer in a simulacrum of a gallery. Wearing a Meta Quest headset, we saw versions of Opie’s signature depictions of urban life—its people, animals, and architecture—rendered in pared-back outlines that resemble street signs or wayfinding. We needed not imagine we were walking because Opie placed us in a navigable space where the work unfolded as we marched through its seemingly unending cycle of rooms.

When Opie first created “Imagine you are walking,” he offered an optimistic outlook on the ways in which urban life would be shaped by the burgeoning field of computer-generated design, endless wandering enabled by technological innovation. The drawings and the walkthrough were openings for explorations into the nature of living in a virtual world—concerns that are now more relevant than ever. While OP.VR.01 is certainly novel for the artist, it’s unclear to what end: the line between personal experimentation and public presentation seems to slip. At his best, Opie is a keen observer of the signs and patterns that underpin everyday urban life. The strongest works in the VR experience were a series of dancing figures created in collaboration with his daughter Imogen, a professional dancer, based on a popular TikTok dance. Under its outwardly mundane wrapper, the work touches on themes of repetition and dissemination on the internet—a father’s celebration of his child’s success tinged with a hint of paternal concern.

Jonah Goldman Kay is a writer and researcher based in London and New Orleans.

In November 2013, a digital drawing of a wizard, with the text “Magic Internet Money” scrawled to the side, was submitted to an open call for an ad for the /r/Bitcoin subreddit. The image was charmingly unskilled; you can see the cursor’s blue zigzags in the wizard’s robe, thanks to the spots where they spill over the black outline, and the white gaps they didn’t fill in. Despite this—or more likely, because of it—the ad was wildly successful. Many Reddit users posted that it was the best ad they’ve ever seen, /r/Bitcoin saw a spike in subscribers, and in less than a month the price of Bitcoin shot from 287 to 1132 USD. This past January, a programmer released a tool for inscribing files on Bitcoin blocks—a new kind of NFT that saves media to the chain, rather than linking to it as is common in Ethereum NFTs. There was a gold rush in Ordinals, as these tokens are called, as artists and developers vied to be early adopters. One such project is Taproot Wizards, a riff on the Magic Internet Money ad. The artist FAR used generative AI to produce 2,105 new wizards based on the original and presented them as unique figures with varying traits—baldness, beanies, glowing eyes—set against different backgrounds, using the layering techniques and rarities that have become standard in the production of PFPs.

Several Ordinal collections clone popular Ethereum NFTs; there are Ordinal Punks and Ordinal Apes, as well as Bitcoin Rocks. Such inscriptions—as Ordinals are often called—seem a bit like graffiti, the spread of well-known tags to mark fresh territory. Taproot Wizards is similarly derivative in its use of the familiar form of Ethereum PFPs, which it injects with Bitcoin-specific lore. The wizard imagery, old and new, both mocks and reinforces faith in the performative force of code—as it is written, so it shall be—that creates Bitcoin’s value. As PFPs, Taproot Wizards signal that their holders ascribe to this belief, so collecting becomes a kind of social performance. The fact that these low-quality, compressed images are inscribed on-chain refreshes the awe at of internet money magic, appealing anew to the power of code to conjure pictures.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.

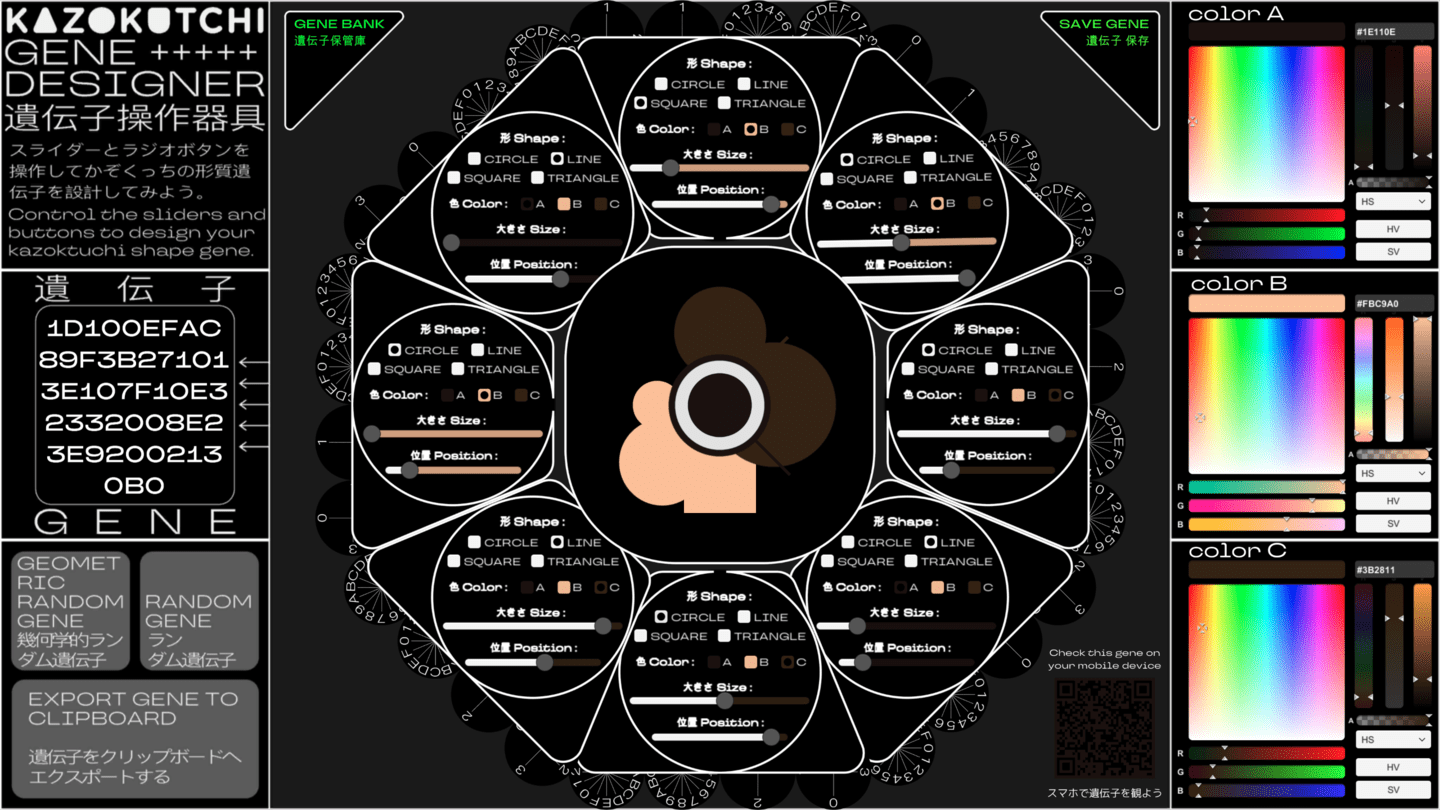

The hype for Tamagotchi isn’t over, at least not in Japan, where new iterations are released annually. Bandai’s iconic ’90s toy is a kid-pleasing artificial life simulation. It was also a starting point for artists Kanno So, Kato Akihiro, and Watanuki Takemi, whose ever-evolving Kazokutchi (2020–) is a playful yet complex work that combines crypto art and robotics.

In an installation on view this winter at ICC Media Center in Tokyo as part of the exhibition “Life/Likeness,” robots built by the artists stood in a vitrine. These robots are referred to as “houses,” and when two of them are close enough, the artificial digital creatures periodically “breed,” and NFTs are automatically minted. Information about the new Kazokutchi’s name, date of birth, and family tree is added to the associated record on the blockchain. Screens looming over the plinth at ICC Media Center displayed this data, with real-time updates. But access to this information is not limited to exhibition spaces. Updates on the Kazokutchi family’s evolution process are available via web browser to holders of the NFTs. The project fully embraces the ethos of web3: the community owns the project.

The Kazokutchi project unfolds simultaneously in physical and virtual spaces, as well as on the blockchain. The new social experiences that emerge from on-chain technologies are at the core of its speculative narrative. Owners are invited to participate in governance and build community around the project. The story of the artificial life forms thus asks us to think critically about the social structures that we take for granted, and how inclusive on-chain decision-making processes can lead to a stronger sense of shared purpose.

Benoit Palop is a writer, curator, and content strategist based in Tokyo.