Handwriting in the Keyboarding Age

Generations of artists have experimented with automated handwriting, illustrating the ongoing entanglement of humans and machines.

For decades, the seven-segment display has been ubiquitous wherever numbers need to be shown—gas station signs, microwave readouts, and elevator displays all use a variant on this device. In Digits (2014–23), artist duo Andreas Gysin and Sidi Vanetti placed thirty-six of them next to each other, then programmed each of the electro-mechanical segments, or “blades,” to operate in tandem, forming a series of abstract shapes. The centerpiece of Gysin and Vanetti’s exhibition at Verse in London last month, the large installation cut across the room, the blades reverberating as they opened and closed. Bypassing the device’s intended purpose as a tool for conveying information, Gysin and Vanetti break it down into its constituent pieces and reassemble them in patterns that, paradoxically, heighten our understanding of the machine’s function.

The duo’s collaborations date back to 2000, when they teamed up for a thesis in visual communications at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Ticino, Switzerland. At the core of their practice is the desire to organize the opaque and seemingly nonsensical operations of computer systems into a comprehensible visual language. In 64 Pixels (2022–23) from their “Matrices” series, the duo programmed an LED panel with 64 individual pixels to light up in a variety of patterns. While 64 Pixels has a fixed frame, another work in the series entitled Recursive Tile (2023) takes the form of an 8×8 tile that duplicates itself to form a larger composition.

The physical editions of the works in “Matrices” each have an online counterpart, minted as an NFT, which displays the same arrangement of pixels and can be viewed on any browser and via an app on your phone. Though the NFT can be purchased on its own, buying an LED panel requires ownership of the corresponding NFT. The panel may have formed the conceptual starting point for the work, but its visual language transcends the limitations of that now old-fashioned device.

Jonah Goldman Kay is a writer and researcher based in London and New Orleans.

Exhibitions have always been as important as sales for Feral File, the NFT platform launched in 2021 by artist Casey Reas. From the beginning, curators were brought in to collaborate with artists on solo or group shows on the platform’s website. Now, in its new incarnation, the exhibition itself is for sale. The Feral File 2.0 program—inaugurated this July with “N=12,” curated by Aaron Penne—will consist solely of group shows, with every artist contributing a series of unique pieces. Collectors purchase an entire “set,” containing one piece from each series.

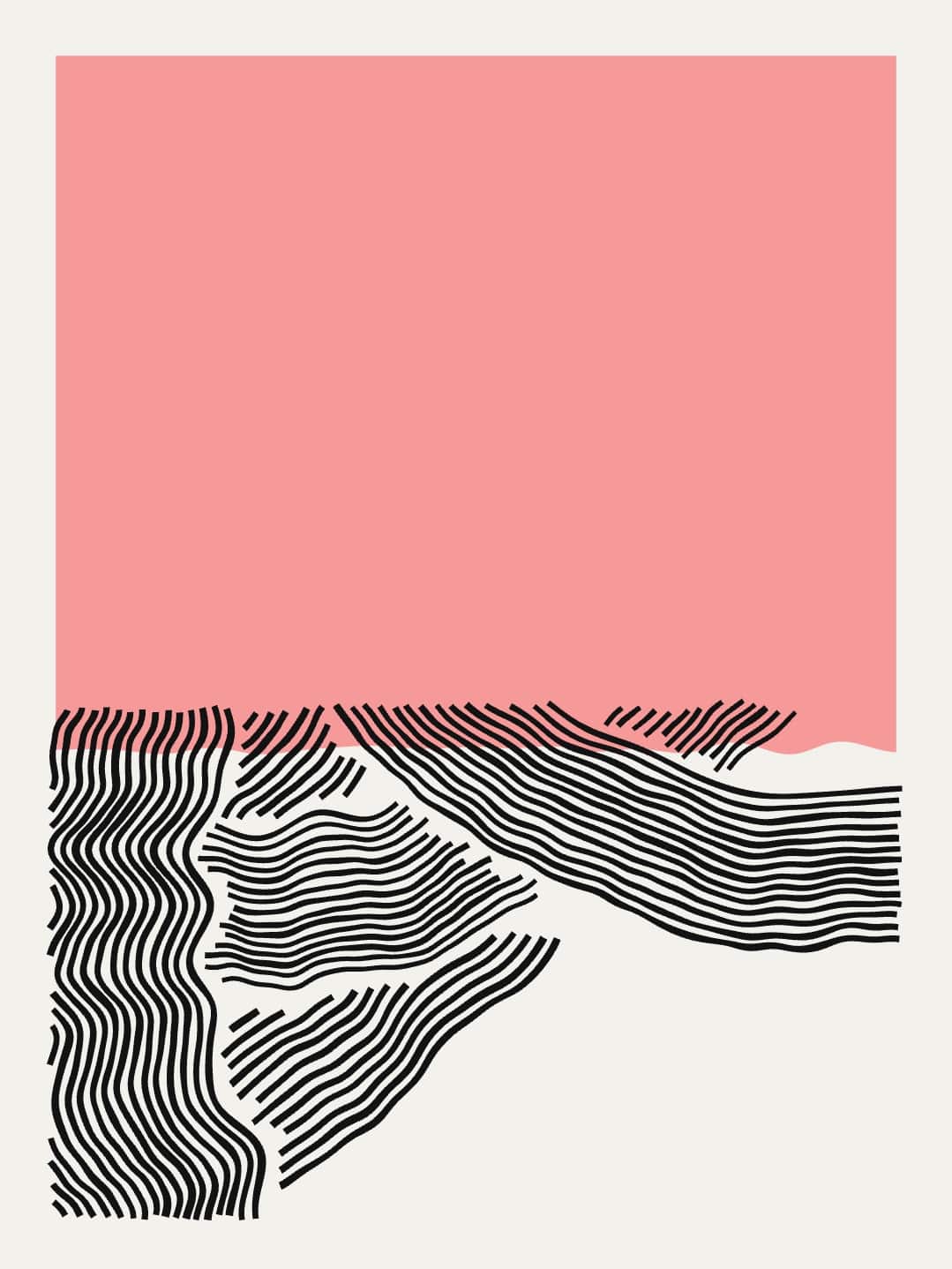

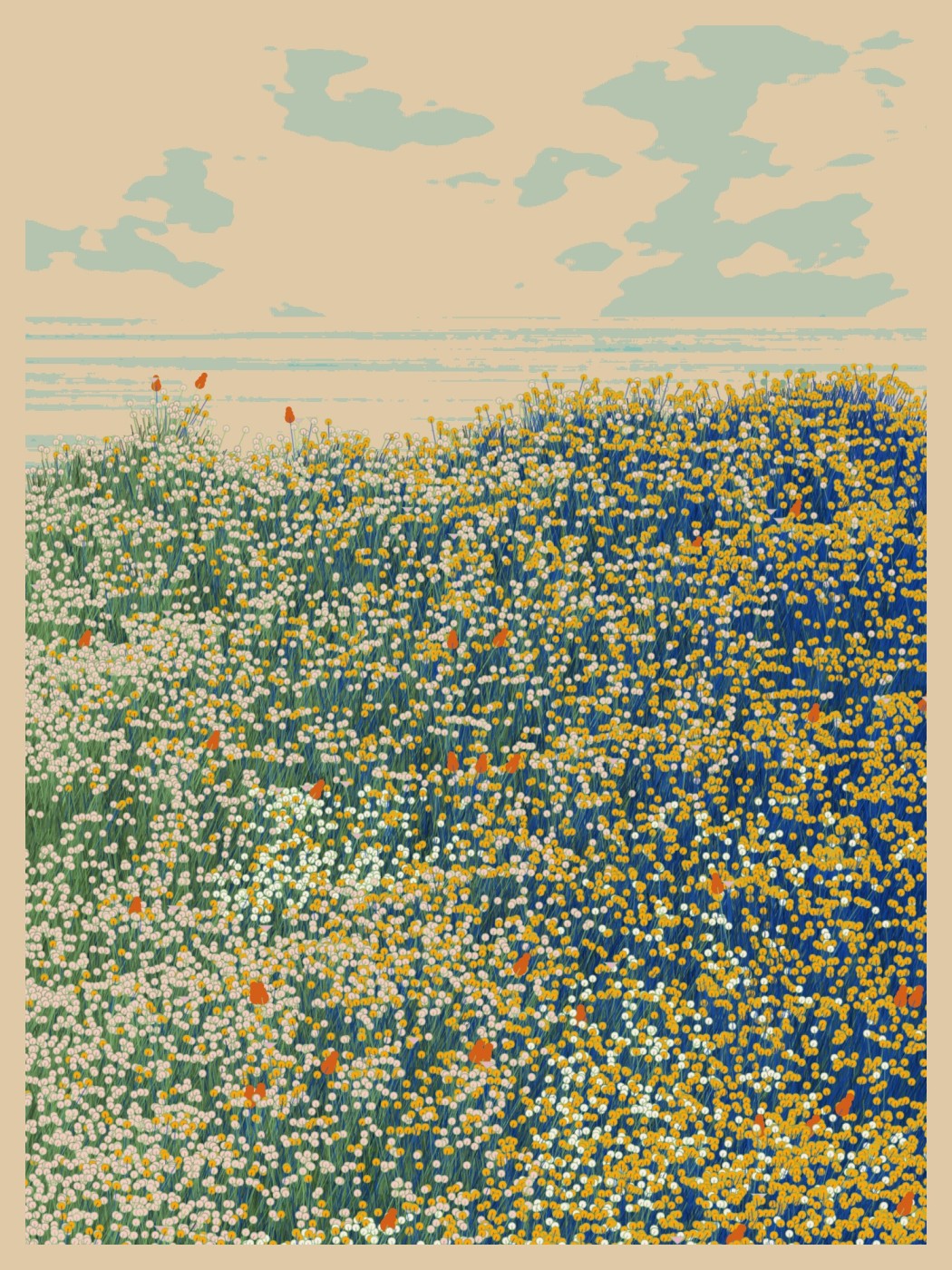

The idea of the exhibition as a creative, collectible product in its own right is cleverly folded into the structure of “N=12.” Twelve artists, all members of a club for generative artists founded by Penne in 2018, have each contributed a new code-based work with 144 outputs. The results are stylistically varied, ranging from Nadieh Bremer’s minimalist arrangements of line and color (wavʌves) to Piter Pasma’s uncannily photorealistic mises-en-scène(Balls to the Walls). But they are also closely if invisibly connected, because the artists honed their algorithms over a period of several months, during which they were in continual communication. In weekly meetings they shared aesthetic feedback, code fixes, and tools. Finally, the outputs were minted and placed in sets using a pseudo-random number generator, or PRNG—so that the sets too could be thought of as generative artworks. During a virtual exhibition walkthrough, the artists and curator compared notes on their favorite combinations. And how did Penne feel about ceding control to an algorithm? “I always say you have to trust in the PRNG gods,” he observed.

Gabrielle Schwarz is Outland’s deputy editor.

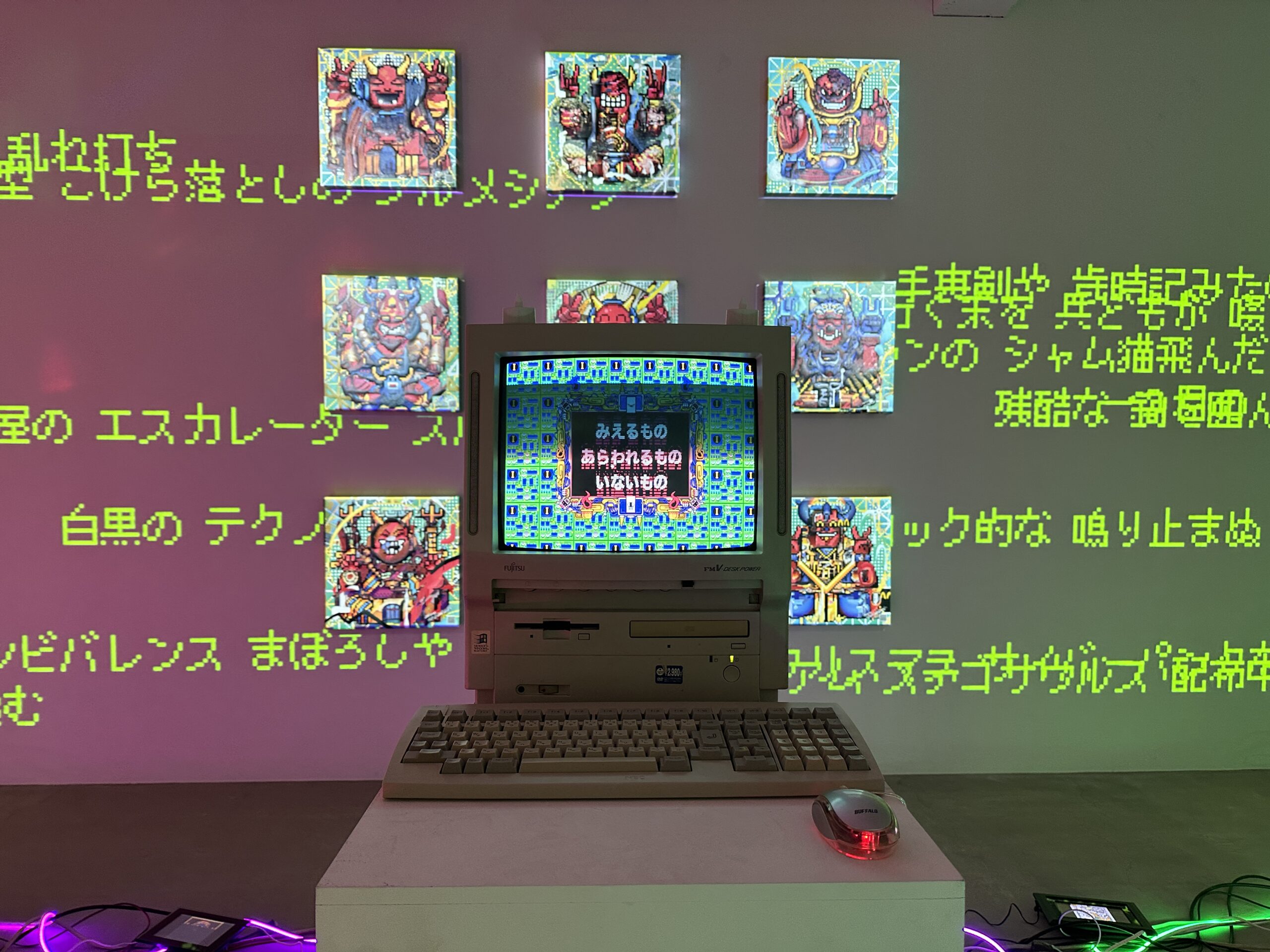

Takakura Kazuki’s exhibition at NEORT++, a space for digital art in Tokyo’s bustling east, paid homage to surrealism and Japanese folklore through the contemporary lens of artificial intelligence. Visitors were invited to select resonant Japanese syllables from a curated pool to draft a haiku, which ChatGPT then transformed into English poems. Another AI devised by the artist generated a visual representation—a supernatural entity known as yōkai, summoned by poetry.

The gallery was scattered with screens and tablets, along with various cables and connections. At the center stood a computer, the core machinery that generated the haikus, then English poems, then yōkais, while the other devices served as displays to welcome these characters. The visitors’ haikus were projected on the walls as they were being composed for an interactive experience. The syllables selected for each haiku determined the features of the yōkai, which were all rendered in Takakura’s signature 8-bit style, reminiscent of the bestiaries of ’90s JRPGs. These were minted as NFTs and collectible on-site via QR code or URL through OpenSea. The collaboration between the artists, viewers, and AI yielded many on-chain yōkai, representing the possibilities when our imaginations converge with computing power.

Benoit Palop is a writer, curator, and content strategist based in Tokyo.

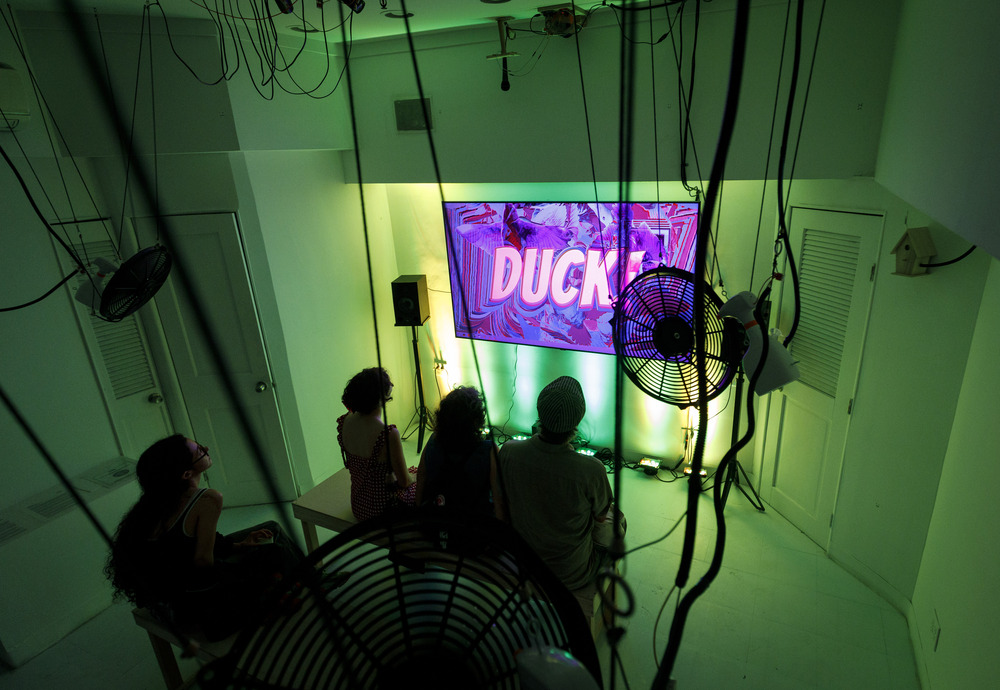

Mark Fingerhut’s Halcyon.exe The Ride is a piece of software programmed to arrest a PC for a 20-minute desktop performance. In a playful and lyrical voice, Fingerhut addresses the viewer as the protagonist in a second-person narrative. Choreographing the computer’s OS, pulsating kaleidoscopic visuals and text are juxtaposed against images of Fingerhut’s living space, which evoke the mundane shut-in experience of the pandemic. Yellow type moves across an elongated black pop-up window: “You had a dream again: a container ship was waiting in line.” The image of cargo-hauling vessels carries a wordplay of “weight” and “wait,” while introducing the supply chain that makes possible the lightness of online life. Animated characters interject: a duck crosses the screen, later introducing an owl who seeks communication: “Duck, can we talk for a second?” Striking scenes combine reverberant poetics with punchy typefaces accompanied by audio of cracking thunder.

When it was installed this June at Public Works Administration, a gallery for digital art in New York, the work’s rigging included rumbling seating, timed lighting, and occasional bursts of scented mist. There was even a microphone that slowly suspended downward during a karaoke scene, inviting the audience to perform. Fingerhut’s malware asks viewers to contemplate their position in a wider context of interconnectivity. The ride as an extension of the software is a Rube Goldberg-esque experiment in immersion. Fingerhut underscores the malware with the installation’s visible circuitry, manifesting the heavy materiality of high-speed information economies.

Halcyon.exe: The Ride is on view at Sulk Chicago through August 10.

Jason Isolini is a new media artist based in New York.