How Legends Are Made

James Jean updates the epic tradition for contemporary values of self-determined identity, inviting his viewers to imagine themselves in his myths.

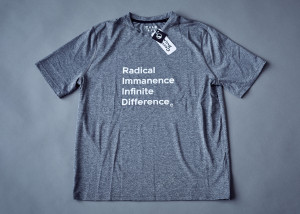

At the top of the website for New Peace is a picture of tundra at sunrise, snow melting off the rocks. The image is digitally rendered, but you can only tell if you zoom in; then it looks less like a stock photo and more like a screenshot from Elden Ring. “New Peace,” explains a bar of copy written in white Arial, “is a new protocol for understanding one’s place in the vastness of time and space.” It is “post-secular,” “mysticism for the anthropocene,” a spiritual relation to “pattern, matter, and energy.” The tab at the top guides you to a store selling athleisure merch in gray and dark blue tones: lush, short-sleeved T-shirts that say “Radical Immanence, Infinite Difference,” or baseball caps with “New Peace” embroidered in the same color as the fabric. It’s the kind of stuff you might wear if you worked in tech but felt alt. That vibe is reinforced by a page selling NFTs—“ultra HD botanical simulation renderings” of purple thistle blossoms from aerial, fisheye angles. New Peace seems to be a cult with a web store. Should you take it seriously? Its creator probably wants you to.

New Peace is the brainchild of Timur Si-Qin, an artist whose work uses the aesthetics of marketing and advertising not as ironic appropriation but as a means to earnestly communicate a worldview in which human activities like technology, commerce, and spirituality appear as natural as birds drinking thistle nectar. The NFTs—titled “Cirsium Vulgaris” after the scientific name of the depicted weeds—recall real estate walkthrough videos, with their soundtrack of spare, ethereal piano music and running water. They aren’t unpleasant. They also recall photoshoots published in DIS magazine about a decade ago, which replicated the language of commercial media with a few tweaks to make the imagery feel funny or vaguely “off.” The similarity makes sense, given that Si-Qin was featured in several such shoots, including “Competing Images,” where models re-created stagings of everyday objects—avant-garde merchandising displays—in works by him and Katja Novitskova.

Should you take New Peace seriously? Its creator probably wants you to.

In a 2013 essay for DIS, Si-Qin argues against using the conceptual lens of Marxism to understand why certain images are propagated by stock photography and advertising. “A common view from the critical theory direction,” he writes, “would be that ideological forces, such as ‘capitalism’ or other forms of authority have programmed our psyches to respond to these images, making us better, more manageable consumer-citizens.” His own strain of critical theory uses bioessentialist reasoning cushioned in New Age spiritualism to insist that the repetition of visual tropes across stock photography is not due to social forces at all. “Evolutionary factors,” he writes, “determine the existence of common image solutions.”

As the 2010s continued, Si-Qin’s subject matter expanded from stock imagery into a broader aesthetic analysis of brands. In a 2016 interview, he explains that his work uses brands as a medium the way painters used easels and paints. Branding, for him, is “a kind of topological sculpture that can be expressed in various spaces and times.” Peace was a pseudo-fashion company that made occasional appearances throughout Si-Qin’s work. To emphasize the vitality of matter, in line with then-trendy object-oriented ontology, Si-Qin rebranded Peace as New Peace, which he described as a “a kind of materialist cult from the future.” The rebrand was announced at Société’s presentation at Art Basel Statements in 2016, where Si-Qin constructed fake prayer rooms for his imaginary religion. The plexiglass cubes, which disturbingly resembled interrogation chambers, displayed nature videos with projections and monitors. “Cirsium Vulgaris” is thus very much an extension of the artist’s pre-existing concerns: climate change, spiritualism, the aesthetics of brands and stock photography. He smears critical theory thick as impasto, more for vibes than anything else. If Si-Qin doesn’t believe in political economy, how could critical theory’s analysis of the political economy of aesthetics be anything more than a mood?

If Si-Qin doesn’t believe in political economy, how could critical theory be anything more than a mood?

The New Peace website explains that “Cirsium Vulgaris” sales will fund New Peace––but what exactly will that money be put toward? More thistle NFTs? More essays like “A New Protocol,” which speculates on the origins of all religions to contextualize the legitimacy of New Peace itself? Perhaps this revenue will be used to expand the website’s “Community” section, which lists New Peace’s “Rituals and Observances (in progress),” and invites the reader to suggest their own. As of now, whoever participates in New Peace observes all solstices, eclipses, “consensual unions,” and deaths.

New Peace seems like a fake cult, but Si-Qin seems to believe in it. Whether or not New Peace is real, its mission is: to use branding to vanish the false binary between humans and the natural world by cultivating a new “spiritual relationship to matter.” If Si-Qin takes New Peace seriously, then he is asking us to do so as well––which means that it seems worth laying out the following critique. The problem with New Peace isn’t a lack of awareness or care about climate change or capitalist alienation, but that its solutions to these structural problems are individualistic, inaccessible, and vague—perhaps because Si-Qin self-consciously rejects structural analysis itself. In a 2017 conversation with Novitskova, Si-Qin pushes back against critics who read his commercial imagery and pro-environment messaging as an accelerationist attempt to heighten capitalism’s contradictions. “We uncritically equate markets with monopolistic corporations and believe that everything that humans create has something to do with commerce,” he says. “Evidence shows that cultural and commercial images are much more determined by the dynamics of cognition rather than any single ideology.” While focusing on geologic time successfully provincializes capitalism, discouraging us from examining it at all feels like standard bioessentialism, in which “natural” or “scientific” factors trump political economy every time.

But critiquing New Peace for being so toxic yet so serene only reinforces an individualist approach. A more generative inquiry might instead ask what New Peace and its well-meaning confusion are symptomatic of. New Peace is similar to wellness culture not just in its aesthetics but in its grift. Wellness culture, like NFTs, are a neoliberal solution to austere times: find happiness however you want, so long as it occurs within a framework of consumer choice. Wellness culture, like NFTs, claims to decentralize power while further consolidating it along existing axes of power. Taking a different route, we could say that Si-Qin saw the death spiral of contemporary art and wanted to make something different—something beautiful, collective, and real. But making anti-art art only leaves you where you began. Which is worse: that New Peace is a cult, or that no one is joining? The unfinished “Community” tab hovers sadly on the screen.

Charlie Markbreiter is managing editor of the New Inquiry.