Criticism

Manual Override

by Jo Lawson-TancredIn the work of Tyler Hobbs, the relationship between humans and machines is filled with productive tensions.

“I’m showing work that I don’t think would necessarily succeed in a purely digital environment,” Tyler Hobbs told me in March during the installation of “Mechanical Hand,” his recent solo show at Unit London. The exhibition was immediately followed up by another brick-and-mortar presentation, “QQL: Analogs,” at Pace Gallery in New York. It’s a move that may surprise those who know him as the creator of Fidenza, the NFT collection released on Art Blocks in June 2021. The algorithmically generated digital compositions sold out in just twenty minutes and resale prices soared as high as 1000 ETH (then 3.3 million USD) that summer. This triumph established Hobbs as a leading figure in the new market for generative art NFTs. But Hobbs has a long-standing drawing and painting practice, and has always been invested in the hybridity of code and physical artworks. He belongs to a long lineage of artists, from computer art pioneers such as Vera Molnar and Frieder Nake to mainstream artists such as Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt, who have explored the creative possibilities of procedural processes whether conducted manually or by computers. His work presents the relationship between human and code as a collaboration, albeit one with productive tensions.

Hobbs has a long-standing drawing and painting practice, and has always been invested in the hybridity of code and physical artworks.

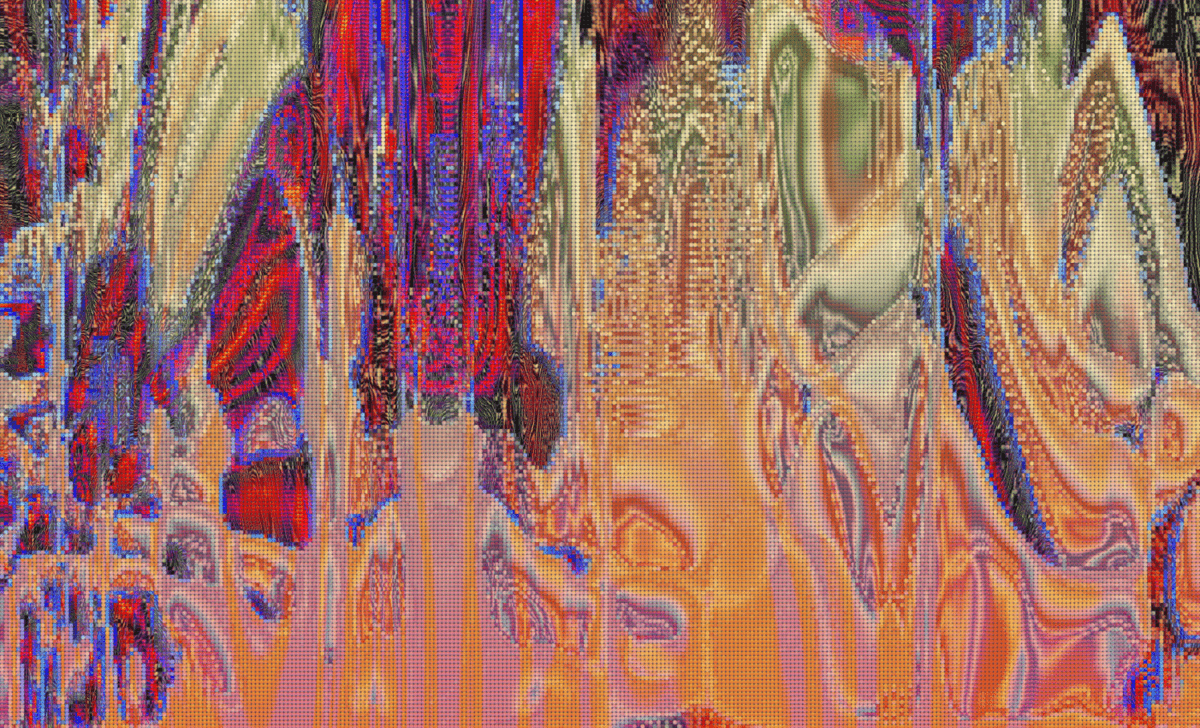

The boom of interest in NFTs in 2021, however, put the focus on digitally native art—it was in this context that Hobbs programmed Fidenza. Each of the 999 compositions, though static, appears to swarm with strong currents of lines. These swirling and undulating lines never look messy or overlap thanks to an underlying mechanism known as a flow field. There are fourteen possible color palettes, each selected by Hobbs to contain complementary shades but with a randomized distribution for each iteration. The lines themselves are determined by a vast array of possible combinations of curvature, shape, and scale. The programmed randomness, as Hobbs explained, helped “to prompt new ideas that I might not have imagined on my own.” Historically, the variety of possible outputs in procedural art has required the curatorial intervention of a human eye in the final stages to select only the best or most interesting. The size of the “curated set” would usually be quite small. Because of the minting mechanism created by Art Blocks, Hobbs’s code was activated each time a collector minted an NFT, and the output was immediately public and permanent. Instead of a handful of plotter drawings, hundreds of digital images came into existence. Hobbs had to ensure that each one of these chance outputs would be of the same quality, and belong to a consistent and cohesive aesthetic. This programming process is what Hobbs termed “long-form generative art.”

His subsequent projects have continued to examine the outcomes when human and machine work in harmony and according to their respective strengths. The London show brought together a range of experiments on canvas and paper. A small number were produced entirely by hand or by machine but the bulk resulted from processes intended to test and transgress the boundary often drawn between these two modes of production. For example, in Aligned Movement (2020), the algorithm was programmed to generate a design based on a hand-drawn gesture as an input. The artist went back and forth between refining the algorithm and refining the gesture to arrive at a design he was happy with. This composition was then brought into the physical world by a robotic plotter, with Hobbs adding paint to the paper—sometimes according to the algorithm’s suggestions, and sometimes intuitively—by hand. Works like this intentionally amplify the differences between the manual and the mechanical. Although we may perceive computers as fully embedded in our world, Hobbs believes our relationship to them is still in an “adolescent” stage. “Our world and the world of the computer are so different,” he said. “There tends to be a gap or a strangeness between what we’re used to in the natural world and the way in which computers behave. I think we have trouble relating to computers.”

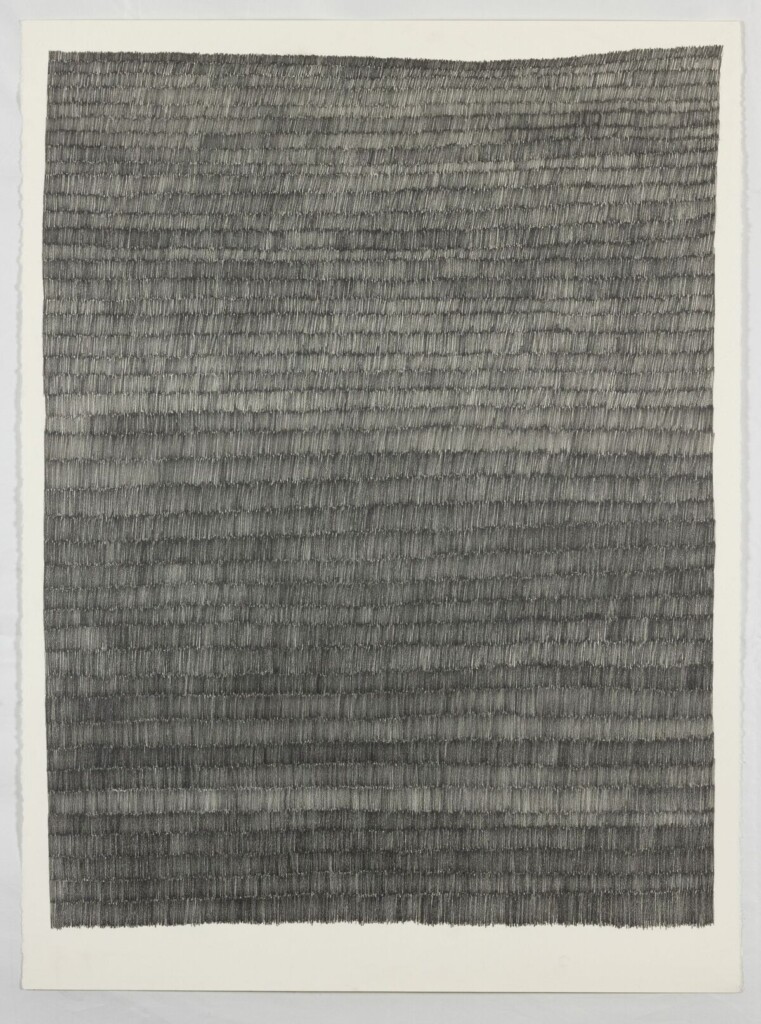

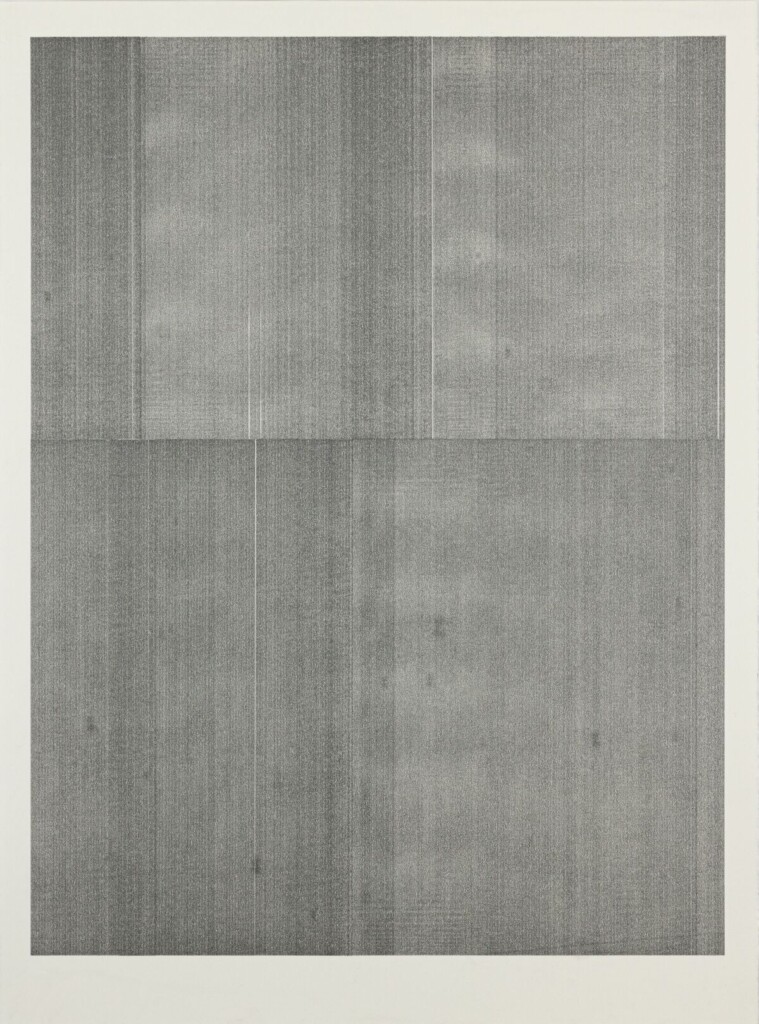

In the sister pieces Fulfilling System 1 and Fulfilling System 2 (2020), Hobbs contrasted mechanical and manual approaches to covering an entire sheet of paper with graphite. In each case, the physical environment introduced natural variations that would need to be programmed in computer-based images. In Fulfilling System 1, the entirely handmade version, Hobbs’s palm left smudges across the page while the shifting pressure on the pencil produced uneven pigmentation. Toward the bottom, Hobbs’s tiny lines begin to slant. In Fuilfilling System 2, the mechanical version made with a plotter, we see the underlying pattern of woodgrain and alignment issues that occurred when replacing graphite or positioning the machine over the paper. Hobbs referred to these as the “machine’s fingerprint, just like the hand has its own.” Paradoxically, by taking a strictly procedural approach, Hobbs is able to bring out the imprecisions and deviations that naturally occur in the process of creation—whether coded or not.

Return One [Red], 2021–22, is a disorienting composition designed using flow fields and executed by a plotter with an airbrush on raw, unprimed canvas. The overall effect is clean and precise—but look closely and you’ll notice subtly softened edges that warm the design. Though the work was executed by a machine, computers are still largely advancing a human vision rather than conceiving a work of their own. Hobbs’s intention lies behind every programmed parameter as well as the custom-made robotic hardware, for which he chose which colors to use, the number of layers and the preferred air pressure.

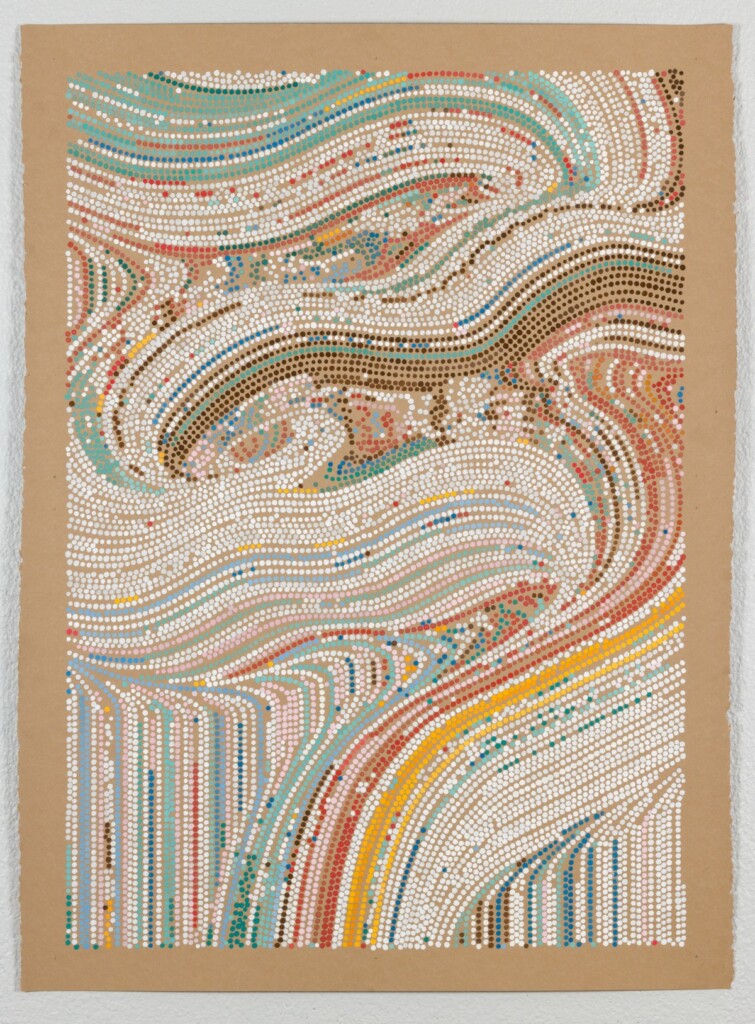

The smaller, more focused show in New York, which runs through April 22, introduces the QQL algorithm that Hobbs developed with fellow generative artist Dandelion Wist and launched online at qql.art in September 2022. The algorithm was made available for artists and collectors to make their own works, and more than twenty million images have already been generated from a wide range of possible attributes determining the composition’s density, flow, and scale. Here, twelve have been translated onto large-scale canvases. QQL: Analog #1–3 (2023) feature large concentric circles that would be almost impossible to draw by hand. Instead, Hobbs used a machine to cut stencils before hand-painting the shapes to regain control over the textural details. For the smaller swirled shapes in QQL: Analog #4–7, Hobbs used a brush to add paint freestyle, directly onto the canvas. These marks are all unique and unpredictable, so that at a distance the algorithmically determined composition remains intact but close-up it comes alive with natural variations. Finally, a more complicated “subtractive” mechanical painting process produced the wall of small swirls in QQL: Analog #8–10, for which a robot’s repeated motions removed a thin film of wet paint, creating the intended pattern by revealing the layer of dry paint below.

Accepting that we can’t draw concentric circles or airbrush evenly is easy enough, but can we admit to limitations on the generative power of our imaginations?

For Hobbs, both shows illuminate the role of human expression, but they also prompt visitors to consider where our capacities fall short. “Computers are much better at many things than we are,” he said. “We really benefit from learning how to not compete head-to-head with these technologies but to harness them.” Accepting that we can’t draw concentric circles or airbrush evenly is easy enough, but can we admit to limitations on the generative power of our imaginations? Hobbs seems ready to do so, casting algorithmic art as a means of expanding the mind’s eye. Nonetheless, there is a question over whether an algorithm not programmed by humans and therefore not reflective of our own intentions—perhaps one trained on the archives of the internet, for example—could “make something that we find meaningful or beautiful or harmonious.” For now, at least, humans are still guiding the process.

Jo Lawson-Tancred is European news reporter for Artnet.