Holographic Media

Media is no longer linear. Legacy outlets fade into noise, and communities have become filters through which all platforms are accessed.

On January 10, 2024, the US securities regulator approved the first US-listed exchange traded funds (ETFs) to track bitcoin. The next day, 4.6 billion USD worth of ETFs were exchanged—a watershed moment for the cryptocurrency industry. I viewed these enactments as a kind of ritual performance, endowing Bitcoin with the aura already inherited by the US dollar when the gold standard was broken in 1971.

In February, not long after Wall Street listed its first Bitcoin ETF, I was invited to participate in the first Sotheby’s auction of Ordinals—digital assets that are like NFTs, but to me far more interesting. After those first trades, Ordinals by proxy had the mythological status of gold.

Of course, Bitcoin had been known as “digital gold” for some time. On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, triggering an international banking crisis. On October 31, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper, which literally equated the cryptocurrency to gold, and named the encryption process “mining”: “The steady addition of a constant amount of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. In our case, it is CPU time and electricity that is expended.”

The aura of Bitcoin was now newly enhanced by its stock-market listing.

But the aura of Bitcoin was now newly enhanced by its stock-market listing. To better understand the implications, I contacted Rhea Myers, whose knowledge of cryptocurrencies is profound. She gave me a reading list of histories of digital currencies that were published in 2022–23, as Bitcoin was ascending in the global financial market. These books chart finance, science, business, and digital art. They are also cosmological narratives that express symbolic structural relationships and universal orders, where utopia’s glow emanates from just over the horizon. I spent the next month reading these books. This essay is a story of these stories: how mythmaking made a technology seem inevitable.

In Norse mythology, Idun is the goddess of youth. She has a basket of golden apples that keep the other gods young—until the end of the world.

In the open-world sandbox game Minecraft (2011), golden apples bestow special effects on players, keeping them alive longer, and heal zombie villagers.

Extropianists were adherents to a cult of the golden apple, in pursuit of immortality. They were an on- and offline group of Bay Area technologists instrumental in developing the coding language and culture that envisioned, designed, and finally encoded Bitcoin. Among those who attended meetups between 1994 and 2005 was Mike Perry, overseer of seventeen frozen heads and ten frozen bodies submerged in liquid nitrogen at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona. In a 1994 Wired interview, Perry predicted a future in which people will download their mind into a computer and make backup copies that lasts forever. “Immortality is mathematical, not mystical,” he said.

The Extropians aimed to build a society based on self-generating systems of order, in resistance to the legal structures imposed by a federal state.

In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were mummified by wrapping the body in cotton and draping it with amulets. A properly prepared mummy bridged the spirits of the deceased and the offerings from the living. Until Extropianism, the Egyptians were the only culture to have held the preservation of the corpse as a specific religious belief. But there is still a significant difference between the two. The ancient Egyptians believed that the heart, rather than the brain, was the organ of reasoning. It was therefore left in place within the body and, if accidentally removed, was immediately sewn back in.

Death and decay are forms of entropy. Extropianism extolled entropy’s opposite—eternal life, the transhuman or the posthuman. Extropianists prided themselves for being supermen with augmented intellects, memories, and physical powers. Their goal was to build a society based on self-generating systems of order, in resistance to the legal structures imposed by a federal state. To finance it, they defined an anonymous digital currency that functioned outside the physical gold standard, yet garnered its mythologies. Some believe that Satoshi Nakamoto is the pseudonym of Nick Szabo, an Extropian. But even if that’s not the case, the connection between Nakamoto’s ideas and the Extropians’ is clear: both wanted to transcend the structures governing human life.

The proof of work protocol is what enables Bitcoin. One party proves to others, who serve as verifiers, that a certain amount of computational effort has been expended. The system requires miners to compete with each other to be the first to solve arbitrary mathematical puzzles. The winner of this race gets to add the newest batch of data to the blockchain. The winners receive their reward in Bitcoin, but only after other participants in the network verify that the data being added to the chain is correct and valid. As a result, Bitcoin and the other cryptocurrencies do not have centralized gatekeepers. Instead, they rely on a distributed network of participants to validate incoming transactions, adding them as new blocks to the chain.

Proof of work is necessarily relational, performed by a chain gang of players and effective because of that. It can therefore also be thought of as a performative ritual of enactment, as the parties go through the requisite set of actions to affirm value. This makes digital gold conceptually very different from physical gold and the financial standards based on it. It is a process of pure computation enacted by people and machines, together expending massive amounts of energy and heat. In doing so it produces a Marxian metaphor of work: heat driven by time, transformed into a monetary unit.

Proof of work can be thought of as a performative ritual of enactment.

My artistic motivation is to extend the arrow of art history, rather than break from it. When I started working with 3D animation and simulation technologies in the late ’90s, I was still a painter living in New York.

I started writing illustrated books in an era before the term “graphic novel” was coined. We had comix, a punk, political version of the mass comic-book form, meaning a thing not accepted as art (and mostly still not). I was a fan of Art Spiegelman’s cerebral comix Maus (serialized from 1980 to 1991). I was inspired by Spiegelman to produce two fake children’s books based on adult themes of power and its abuse: A Child’s Machiavelli (Realismus Studio,1995) and Dr. Faustie’s Guide to Real Estate Development (Nautilus, 1996), a reinterpretation of Goethe’s Faust.

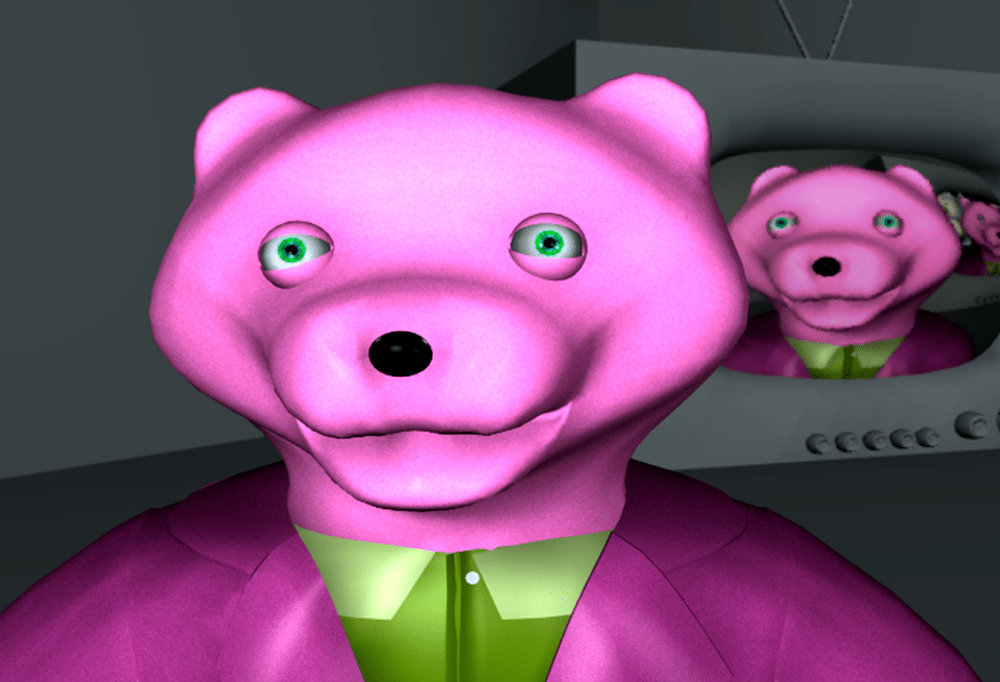

More Life, my animation in the Ordinals auction, featured an avatar that I created in that period. I made a series of six-foot gouache paintings on paper, based on an illustration in Dr. Faustie’s Guide to Real Estate Development. This was my first confrontation with the “not-art” problem. An important New York gallerist sent a collector to my studio. After listening to me explain my paintings and how they used as their source illustrations from one of my books but repainted at a larger scale, the collector pronounced the work “not art” and departed. He intuited that, although the paintings of my Dr. Faustie pages looked like pop art and were made on traditional rag paper mounted on stretched linen using rabbit-skin glue—techniques developed during the Renaissance—they were nevertheless structurally different from it. When Roy Lichtenstein made paintings of comic book pages, he was being playful and naughty, but still acting within the acceptable framework of art. Lichtenstein conceived of comic pages like apples, an element in a contemporary version of a still-life painting.

A few days after the Sotheby’s Ordinal auction closed, February 8, someone unfamiliar sent me an email. He’d just bought a small untitled oil painting I made in 1994, exactly 30 years ago! It featured the same Dr. Faustie pink bear that figured as the avatar in More Life (2000), the 5-second animation I had inscribed as an Ordinal, and which also appeared in my 1996 graphic novel. He asked what the work was about. It was a painting that combined art and text, as all my work from the 1990s did. I thought of mixing the two as a kind of paradox, related to another impossible belief that inscribing a tiny file into one millionth of one millionth of a Bitcoin embeds it into infinity. A ritual enactment and an impossible thought, a logical syllogism in which language uses itself to cancel itself. A new alchemy.

Claudia Hart is a professor emeritus at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she developed a pedagogical program based on her own use of 3D imaging technologies.