In Search of a Common Language

Participants at an NFT conference in Kassel had trouble communicating across disciplinary borders.

Music has a problem.

Streaming services such as Spotify offer millions of songs at the click of a button. For a low monthly fee, subscribers have instant access to more music than they could ever possibly listen to.

But streaming music spells disaster for the bottom line of many independent artists. Royalty checks are minimal for the vast majority of musicians. The pandemic continues to deplete revenues from touring. And though vinyl has made a major comeback in recent years, pressing records involves considerable costs and long wait times. The artist-friendly digital music marketplace Bandcamp was recently acquired by Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, for an undisclosed sum, leading many indie musicians to worry about the platform’s future.

Streaming music spells disaster for the bottom line of many independent artists.

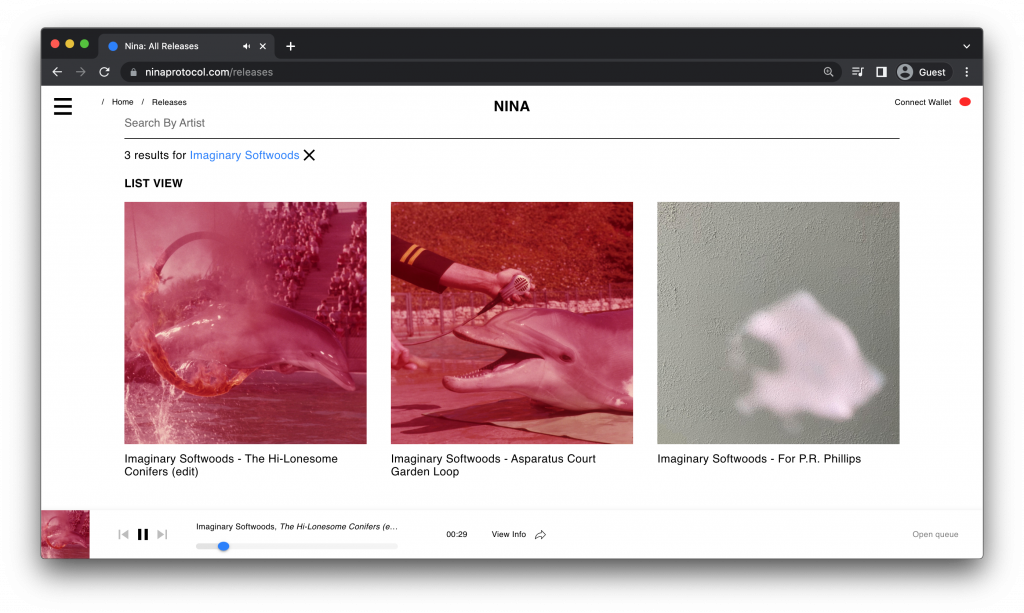

A new wave of web3 music initiatives aims to break the grip of streaming services and revolutionize the ways that albums and songs are bought and sold. One of the most notable is Nina, founded by a small group of music aficionados with deep roots in the underground punk, experimental, and noise scenes. “The reason I like Nina is because it’s an infrastructure, not a brand or a service like Spotify or something like that,” said John Elliott, a member of the noted band Emeralds who also records under the name Imaginary Softwoods. (Elliott currently has several releases on Nina.)

Nina, started by Eric Farber, John and Mike Pollard, and Jack Callahan, pitches itself not as a marketplace or platform but as a protocol, like SMTP, the standard for sending email, or HTTP, the bedrock of the World Wide Web. Their goal is to be a community infrastructure that is not tied to a single website, but can be used anywhere online, by anyone.

Nina, which launched in November 2021, is built using Solana, an open-source, proof-of-stake blockchain, and Arweave, a blockchain-based data storage protocol. Artists can sell albums and tracks as limited editions, receive 100 percent of initial sales, and also benefit from secondary sales, all for a small fee. Buyers need a Solana wallet to purchase an album. But instead of using the Solana cryptocurrency to buy music, users convert Solana in their wallet to USDC, a cryptocurrency pegged to the US dollar.

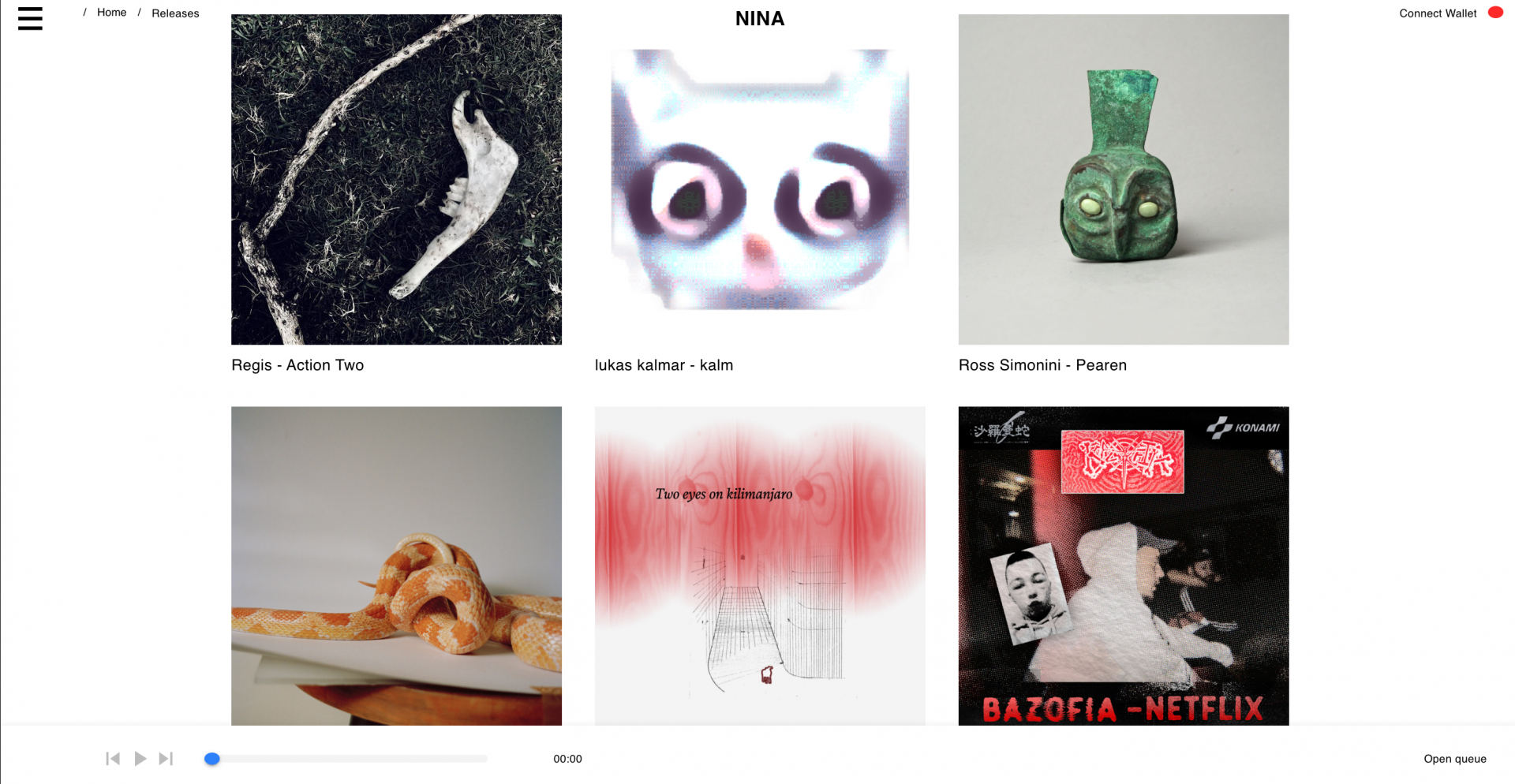

Currently Nina hosts more than three hundred albums and tracks for sale, and the amount of music available is growing rapidly. The website, which sports a clean, slick design, feels well-curated. Many of the artists featured are recognizable to fans of underground electronic and experimental music: Surgeon, Regis, Kangding Ray, Space Dimension Controller, Leslie Keffer, and C. Spencer Yeh, to name a few. Many of the artists hail from Brooklyn, while others are from Berlin and other hotbeds for new sounds.

Listeners can stream any song for free to try it out. The prices to buy a release are reasonable, with the average hovering around 10 USDC. These may seem like modest amounts compared to the vast sums that some NFTs are selling for, but they could add up quickly for an artist. “If you sell 250 NFTs for 10 USDC [each] that’s a huge difference maker for someone,” Elliott said. Accessibility was a factor in the choice of currency. Listing an album at 15 USDC is more inviting to novice users than setting a price at a tiny fraction of a SOL or ETH.

Streaming music is always there, always available. By selling albums in limited editions of, say, fifty copies, Nina brings back an element of the bricks-and-mortar experience—that special feeling of finding the last vinyl record in the store. Digital scarcity helps reinforce the music’s financial value, allowing the independent artist to make a fair profit. “I think that another byproduct that came with the constant accessibility provided by some of the current big music platforms [is] that they created this sense of disposability,” Farber said. “I think that some of the inspiration that we brought to [this] comes from scenes where people were really passionate and cared a lot and shared things—shared experiences, shared objects.”

Nina is a passion project for the small group of founders. “I think that when we had the idea, we felt obligated to do it,” Farber said. “We were talking about it. We’ve all been in the scene for fifteen years; we have the tech chops to actually develop this.”

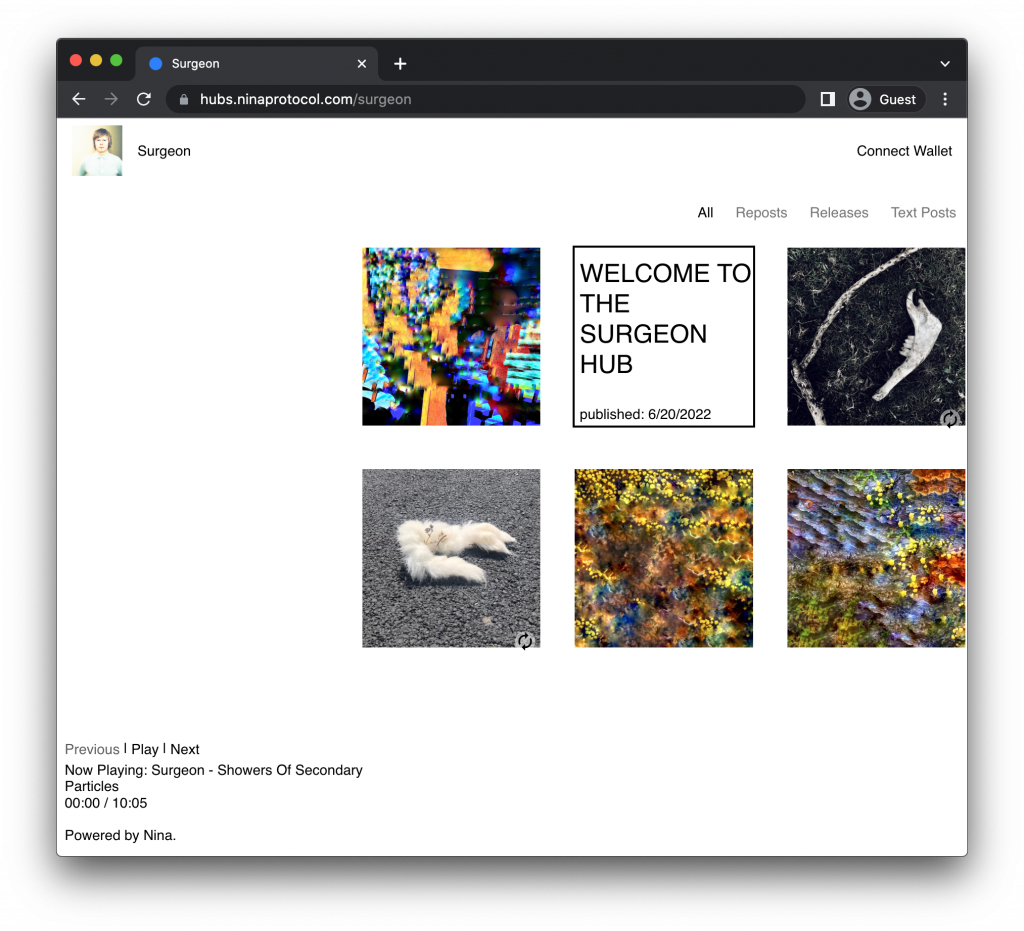

The next big development for Nina is a release called Hubs: individual sites for artists, labels, or fans that are powered by the Nina protocol but exist independently of Nina’s website. “Our goal is to make this toolset available and decentralized totally for artists to just be able to run their own Nina-powered sites,” Pollard said. “Someone can have their own website that they host themselves, that plugs into the Nina protocol on Solana and Arweave and it has no dependence upon any servers that we run—just a program that we’ve deployed to the blockchain.”

Elliott thinks that Hubs is a promising new avenue for Nina, allowing artists even more autonomy in how their work is presented. “People can go from hub to hub, you have these islands of different styles of music,” he said. “Whereas if you’re on Spotify, it’s driving you—they’re just being jammed down your throat by an algorithm.”

But as more artists sign on to Nina, will it be easy to browse and discover new music? Right now the user experience is pleasant, in part because the selection is so small. As Nina expands, perhaps to tens of thousands of albums across a much wider array of genres, the next challenge will be finding a way for listeners to navigate a massive catalog.

Getting artists to sign up for Nina en masse requires raising more awareness about what it can offer musicians, who may be understandably wary of new technologies. One challenge, Pollard said, is presenting the protocol to independent artists who are still bewildered by the “Ethereum NFT gold rush” that overtook the mainstream media narrative last year, wondering how they fit in. This isn’t about being the next Beeple and making millions, but using principles from NFTs to build a community-driven, sustainable model for music sales. It’s a more modest, realistic version of the future—of using cryptocurrency to pay for everyday transactions. He believes artists and fans will catch on.

“If you have an artist who thinks outside the box, and they understand what the protocol is and what the protocol does, it’s a no-brainer,” Elliott said.

Geeta Dayal is a critic and journalist who writes about music, art, and technology.