2022 in Review: NFTs and the Art World

How are attitudes toward NFTs changing in the art world? Seven professionals share their perspectives.

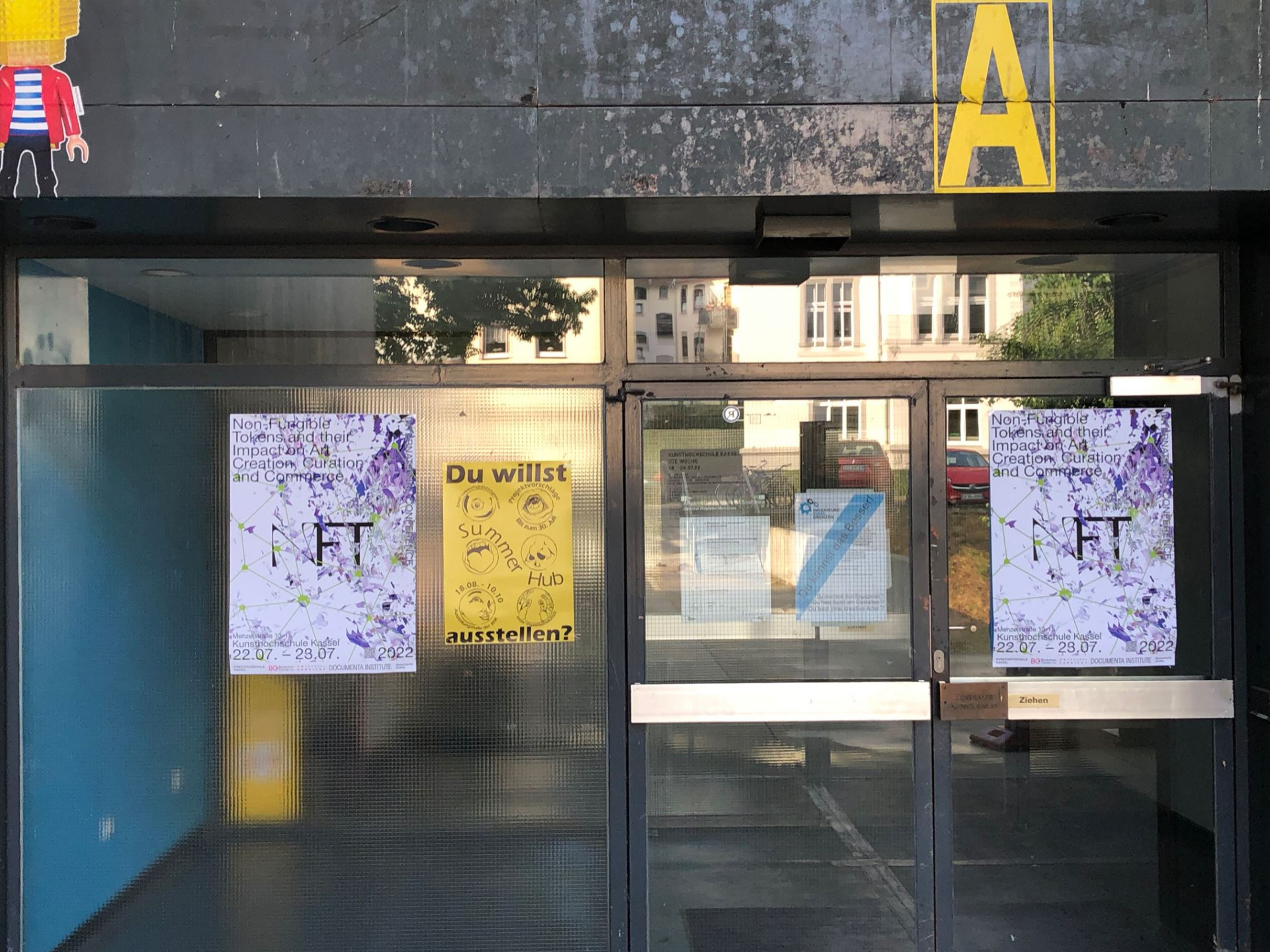

The nonfungible token is a concept from finance that was popularized with the help of digital art. It abstracts ownership in ways that excite conceptual artists and pose unresolved challenges for the law. “Non-Fungible Tokens and their Impact on Art, Creation, Curation, and Commerce,” organized by the University of Kassel’s Blockchain Center and held at the Kunsthochschule Kassel last weekend, was a conference that attempted to foster deeper understanding of NFTs by bringing together specialists from different fields: artists, curators, lawyers, economists. At times these exchanges yielded interesting insights, but more often it demonstrated the difficulty of overcoming disciplinary barriers—how communication breaks down when experts don’t recognize expertise in fields outside their own.

The first day of the conference was amenable enough. Five of the six talks addressed the impact of blockchains on art. Casey Reas, a generative artist and founder of the exhibition and sales platform Feral File, talked about the inroads NFTs have (or haven’t) made in various institutional contexts, from auction houses to art schools, concluding that NFTs are most effective as a distribution mechanism that reduces friction to collecting, which is why they have spawned so many new markets and marketplaces. Regina Harsanyi, an expert in the preservation of time-based media art, explained why blockchains can’t be used as archives, but also emphasized that conservators need to think about how artists are using blockchains when archiving digital works minted as NFTs. The outlier in the morning session was Roman Beck, a professor of information systems and head of the European Blockchain Center in Copenhagen. While most technologies are adopted out of convenience, he said, blockchains are used despite their inconvenience, largely for ideological reasons—by people who don’t believe states and banks should control finance, for example. His center advocates for the design of tokens and protocols that are socially useful, to increase the appeal of blockchain applications in more sectors.

Art professionals bristled at the notion that art’s value could be quantified at all.

Beck’s presentation rhymed somewhat with the following one by Ruth Catlow, director of art and tech organization Furtherfield. She discussed artists’ attempts to overcome the asymmetry between contemporary art’s funding systems and value systems by using DAOs and other blockchain-based technologies to build experimental forms of coordination and collectivity—the subject of Radical Friends, a new book she co-edited. Catlow sees NFTs as a mechanism of the market, irrelevant to the kind of work that interests her, so she didn’t mention them, making a critique through omission. Pekko Koskinen was also critical of the NFT market, but he put blame on terminology. An artist and game designer who works with the blockchain startup Economic Space Agency, Koskinen argued that the financial term “nonfungibility” overemphasizes individuality and prevents people from seeing how tokens behave as members of family structures. The banality is not in the form itself, he said, but in the formalism that has emerged around it, fostering traditionalist attitudes toward digital art.

Tina Rivers Ryan, a curator at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, conducted a provocative thought experiment. Though she often tussles on Twitter with anons who say museums are out-of-touch and elitist, she made a peace offering of sorts, suggesting that the aspirational ideals of blockchains and museums are really not so different. In the best case scenario, both provide transparency, permanence, and ways to be anonymous in public. Auriea Harvey, an artist and professor at Kassel Kunsthochschule, intervened to correct Ryan’s rosy account of museums. People in the NFT sphere are suspicious of institutions not only because of populist or techno-utopian worldviews, but because museums have been “vampiric”—twenty years ago, they treated digital art not as a serious field to support but rather as a trend they could extract value from before discarding. The panel discussion at the end of the day had a similar dynamic, with Ryan forced into a defensive stance as she argued on behalf of traditional institutional forms while Catlow and Koskinen advocated for careful experimentation with new possibilities.

Despite their disagreements, the first day’s speakers held a baseline agreement about art’s value and the need to reckon with the blockchain, if only because artists are using it. This wasn’t the case on the conference’s second day, when art was discussed in the abstract as a use case for NFTs. Edmund Schuster, a professor of corporate law at the London School of Economics, summed up the art market as the behavior of irrational economic actors, and likewise dismissed all blockchain applications as “either pointless or useless” because they don’t fit in existing legal and economic frameworks. Georg von Wangenheim, an economics professor at the University of Kassel, stepped in for Primavera de Filippi, who was scheduled to appear but had to cancel at the last minute—a pity, since as both a media artist and legal scholar she could have helped bridge the conference’s disparate discourses. In his talk, von Wangenheim employed deductive reasoning to describe a situation where an artist’s use of NFTs would be absolutely necessary. He found they were best applied as a means of accessing generative simulations, and acknowledged that such works appeared in Reas’s presentation. It was a funny, even satisfying moment where perspectives from different disciplines intersected, though it also underscored the distance between the conference participants who work with NFTs and the ones who think of them as hypotheticals.

Francesco Angelini, a cultural economist at the University of Bologna who spoke via Zoom due to a Covid infection, compared the construction of value in the markets for fine art and NFTs, which remain distinct but can nonetheless be described in similar sociological terms. His graphs illustrating the various weight given to aesthetics, historical value, social value, and so on in the two markets got negative reactions. Art professionals bristled at the notion that art’s value could be quantified at all. Schuster said this kind of analysis was pointless, because the reasons for purchasing art are irrational and therefore unknowable. (He was either deliberately dismissing a century’s worth of research on the sociology of value, or he was just ignorant of it and decided not to trust Angelini’s citations or credentials.) In the final panel, the differences of perspective came to a head. The moderator introduced a roleplaying game, asking the panelists—Beck, Schuster, and von Wangenehim—to advise a poor artist, a rich investor, and art collector Brad Pitt whether or not they should get involved with NFTs. Their responses relied on economic principles and revealed a lack of knowledge about the realities of the NFT market; Schuster said the artist should “mint everything he can” and hope something sells—a sure way to waste a lot of time and money. The economic and legal experts on stage (all men) and the art workers at the tables in the front of the auditorium (all women) volleyed “well, actually” statements, correcting and qualifying each other, but ultimately failing to achieve mutual understanding.

An interdisciplinary conference can’t be effective unless its participants want to learn from each other.

An interdisciplinary conference can’t be effective unless its participants want to learn from each other. The people from the art side seemed somewhat more willing to do so, maybe because they are used to dialogue among artists, curators, educators, and other kinds of specialists. I got the impression that the production of knowledge follows more rigid paths in academic departments of law and economics. The speakers in those field often commented on how “creative” the art presentations were. Surely they intended it as a compliment, but it sounded condescending, as if those ideas were made up and not grounded in work and research.

A further problem was that the conference on NFTs had virtually no discussion of actual NFTs. Reas focused on marketplaces, Ryan on museums, Catlow on DAOs and collectives. Koskinen gave a rich theoretical discussion of forms that NFTs could take without mentioning any of the NFT projects that have used them. Schuster preferred to speak in hypotheticals; he kept returning to an imaginary scenario where “monkey drawing” NFTs were forced to be transferred to another wallet at gunpoint. Perhaps a more productive topic for future interdisciplinary conferences would be not NFTs in the broad sense but a set of particular NFTs, so that participants could better understand how each other’s perspectives can be brought to bear on actually existing problems.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief