Artists on Games

Mitchell F. Chan interviews artists to understand how games have influenced their work.

On February 20, 2023, Clarkesworld, a highly regarded monthly magazine for science fiction and fantasy, announced an indefinite hold on new submissions. The reason? It was being flooded with stories self-evidently fabricated by artificial intelligence systems, especially ChatGPT launched ten weeks earlier by OpenAI. Publisher and editor Neil Clarke had been spending his days weeding the torrent of spammed submissions. But the effort was not sustainable. Meanwhile, editors at The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and Asimov’s Science Fiction reported similar. “This isn’t a game of whack-a-mole anyone can ‘win,’” Clarke commented, while posting a graph to Twitter illustrating the precipitous rise in Potemkin manuscripts.

The incident received widespread media coverage. Part of the interest, of course, was the specific genre in which Clarkesworld and its siblings publish; indeed, that may well have been what was driving the phenomenon in the first place. What a coup it would have been for someone to place a story written by an AI in a magazine devoted to science fiction!

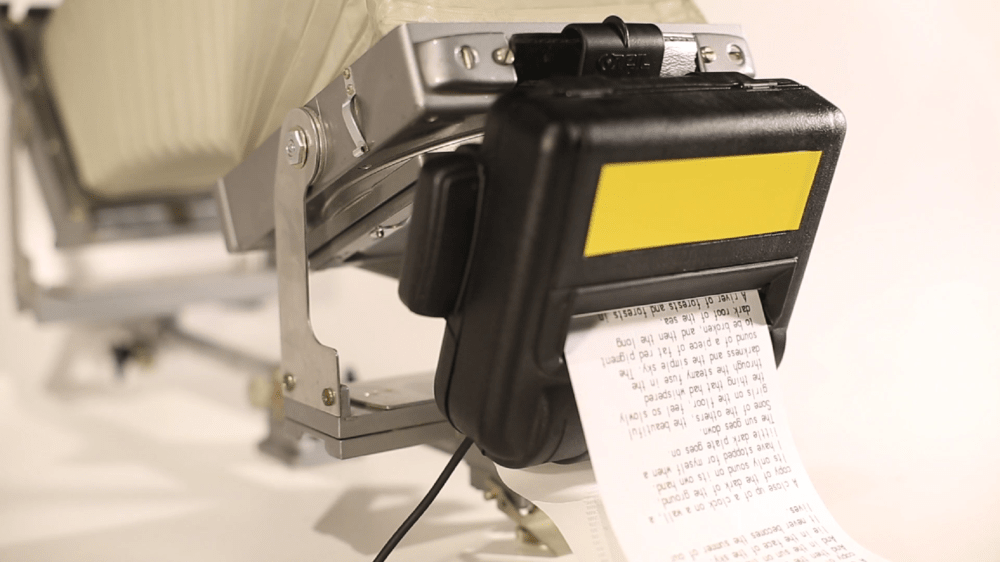

In fact, science fiction authors have long maintained a fascination (some might call it a fixation) for the idea of automated writing machines. The list of notables who have tried their hand at this particular subgenre is a long one: Arthur C. Clarke, with “The Steam-Powered Word Processor” in 1986; John Varley with “Press Enter” in 1984 (it featured characters named for now antiquated brands like Osborne and Lanier), followed the next year by “The Unprocessed Word”; Stanislaw Lem was even earlier, with “U-Write-It,” a sketch of a “literary erector set” consisting of strips of paper (1971); and Roald Dahl even earlier still, with the “The Great Automatic Grammatizator” (1954). Dahl posited a machine that could write a best-selling novel in fifteen minutes and a future in which writers would make their living simply by licensing their name and likeness to its output. Fritz Leiber stretched the conceit to a full-length novel, The Silver Eggheads (1961), which similarly imagined writers maintaining their public image while automated “word mills” did all their work behind the scenes. All of these are examples of a tradition of speculative fiction about writing machines that goes back at least to Jonathan Swift’s narration of Gulliver’s visit to the fictitious and farcical Academy of Lagado, where he encounters a “Word Loom” tended by a professor and a team of research assistants. The Loom consists of words stamped on dies manipulated by elaborate arrangements of pulleys and levers, a contrivance that allows “even the most ignorant person” to write books of philosophy, poetry, and more.

Science fiction writers, of course, were unusually attuned to the promises and perils of computing. When commercial word processors began appearing on the market in the late 1970s they were some of the earliest adopters. One by one the genre’s luminaries abandoned correction tape and carbon copies for the strange new arcana of ROM and RAM. Jerry Pournelle, a prolific author of so-called “hard” science fiction who wrote a monthly column about personal computing for BYTE magazine, was responsible for converting at least a dozen of his colleagues after showing off the homebrew word processor he dubbed Zeke.

While the temptation to fictionalize the new technology must have been irresistible, authors also used the device (both literally and literarily speaking) as an occasion to work through some of their deepest professional anxieties. All the stories I’ve mentioned turn on the balance between lofty ideals of creativity, originality, and the literary imagination on the one hand, and the brute realities of the writing life on the other—namely the constant need to produce new content, and the grueling tedium of the act of writing itself. Time and time again, the machines promise a way out: why should the Good Reverend Cabbage (Clarke’s stand-in for Charles Babbage) spend his earthly days composing variations on the same sermon when a machine can do it for him?

But these authors could never quite permit themselves total emancipation. The reams of automated words always came at a price. Sometimes it was the quality of the prose itself: it turns out that the World Loom Gulliver encounters only ever produces “broken” and mangled sentences, for example. Clarke’s wondrous steam-powered word processor, meanwhile, eventually implodes in a maelstrom of gears, with only one badly printed page supposedly surviving in the British Museum. Elsewhere, as in Dahl and Leiber’s narrations, what’s at issue is the very nature of authorship itself—if the writer is both an artist and a worker, how should these roles be balanced? From Gulliver on down, these stories function as literary shoptalk, occasions for authors to reflect on their craft through the fictional device of the automated writing machine.

Generative AI is a prosthetic not just for the material act of writing but for the writerly imagination.

Now, as the example of Clarkesworld shows, generative AI has moved such narratives out of the realm of fiction and into the day-to-day business of publishing. Despite some initial skepticism—some authors at the time reported hiding their use of word processors from their agents and editors—computers were quickly accepted as part of the writing life. Spell check, as well as more advanced tools like Grammarly and Final Draft—which help writers do everything from fine-tune their voice and argumentation to structure entire scenes—were similarly absorbed. But is ChatGPT a step too far toward word looms and word mills?

The author who foresaw this particular future most clearly may have been Damon Knight, who in 1973 published a story entitled “Down There” in a science fiction anthology edited by Robert Silverberg. It posits a writer-protagonist named Norbert who spends his days in front of a computer terminal in an anonymous grey cubicle. Norbert’s income is derived from syndicated sales of his short stories, which, with the aid of an IBM computer, he tosses off at the rate of one or two a day. His relationship with the machine is symbiotic: it offers him menus of plot archetypes and fictional settings, and it lets him look up factual details like the rules of the game jai alai. It also prompts Norbert with sentences, which he then edits and fine-tunes. The machine is good, but it needs Norbert’s touch. Confronted with an abrupt transition between events he leans forward to tap the screen with his light pen: “There was your computer for you every time, hopeless when it came to expanding an idea,” he mutters. Such observations ring true to us now, as we feel our way with tools like ChatGPT.

After a morning of this, Norbert calls it quits and Knight’s story changes abruptly in setting and mood. Norbert travels to a seedy portion of the city to visit a prostitute, only to discover his favored sex worker has left town. The soutener presents him with an alternate, an “olive-skinned almost Latin-looking woman,” “monstrous in a flowered house dress.” Her eyes are “evil, weary, and compassionate.” The door closes behind Norbert and the story ends.

At stake is not just the integrity of the written word, but also the conditions of labor under which it is produced.

What are we to make of this? The first half was a light sketch. But the second half of the story is something else altogether. Contrasts, such as between the dull gray cubicle in which Norbert works and the brothel, are inevitable. Still, the two halves don’t really cohere. Are we being asked to reflect on Norbert’s own status as a writer and his dependence on the IBM machine? Is the idea that he himself is a prostitute of sorts? Or perhaps the second part of the story is some kind of projected imagining into the dark heart of the creative process, a glimpse of that foul rag-and-bone shop where the muse truly dwells?

“Down There” is darker and more subtle than most other entries in the subgenre devoted to fictional writing machines. Perhaps we’re meant to understand Norbert himself as the offspring of some literary engine, one that (as Knight posits) is not very good at transitions; perhaps Norbert is the product of a machine that starts off writing one story and ends up writing another, with no human to intervene and fix the glitch.

Neil Clarke of Clarkesworld has a real-world problem Knight (best known for his own editorial work on the magazine Orbit) never did. At stake is not just the integrity of the written word, but also—as all these authors understood—the conditions of labor under which it is produced. Most immediately, there is the fear that computers can put human authors out of work, an anxiety that is quickly becoming realized in certain corners of the content creation industry. (In a moment of self-awareness Norbert reflects that he is lucky to have the gig he does instead of being reduced to tabloid journalism or worse.) There’s also the question of the pace of literary production: Pournelle and other early adopters embraced word processing because it allowed them to write more efficiently and thereby produce a higher volume of saleable work. It bettered their prospects for a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Generative AI, however, risks a future in which pushbutton automation is so commonplace that writers—like Norbert himself—might be expected to produce a dozen or more stories a week just to keep their heads above water.

Generative AI risks a future in which writers might be expected to produce a dozen or more stories a week just to keep their heads above water.

Above all, we face a future marked by what I have elsewhere described as an ongoing estrangement from the act of writing. The stick or bone we once used to scratch marks into the earth was the first literary prosthetic, replacing our finger. The typewriter was hailed as both a marvel and a menace in its day (not least because it offered women entry into the corporate workplace). But generative AI can do something none of these other tools ever could. It is a prosthetic not just for the material act of writing but for the writerly imagination.

It’s too soon to know which story we will find ourselves in. Will the new technologies relegate writing to a post-industrial pushbutton dystopia? Or will the machine stop, mauling itself to pieces in its vain attempt to produce facsimiles of human prose? Down there (where the people like Neil Clarke do the real work) the answer may be both/and.

Matthew Kirschenbaum is professor of English and digital studies at the University of Maryland. He is the author of Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (Harvard University Press, 2016) and Bitstreams: The Future of Digital Literary Heritage (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021).

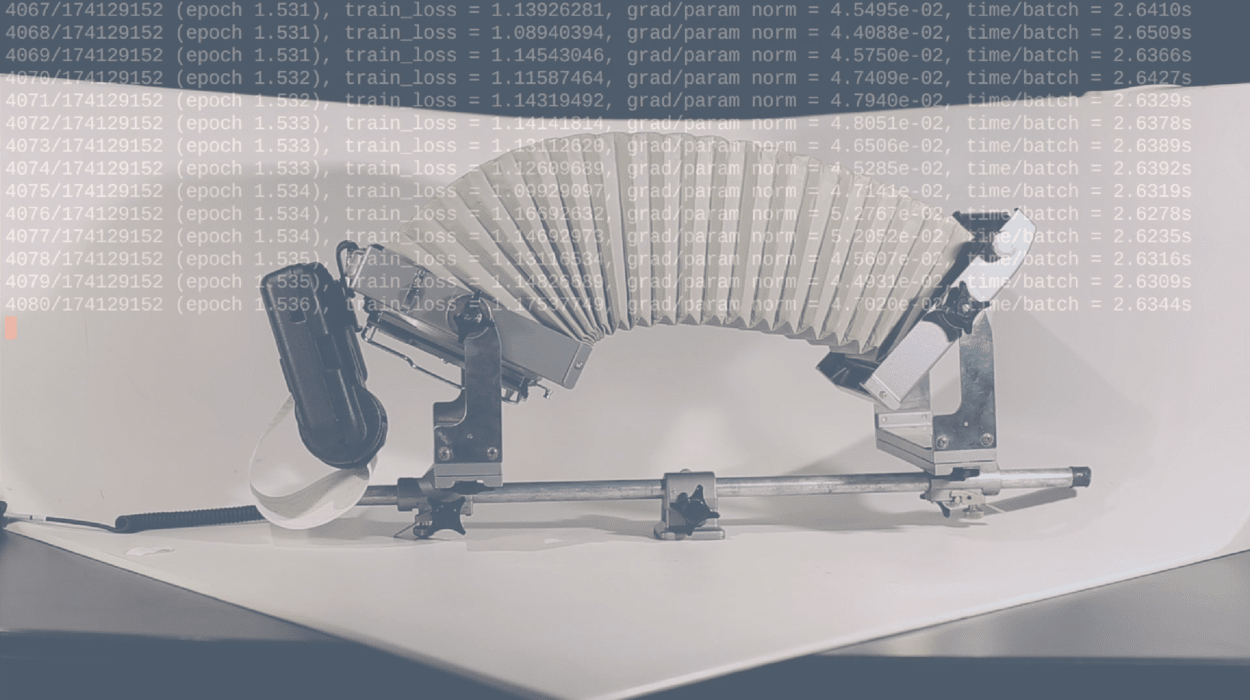

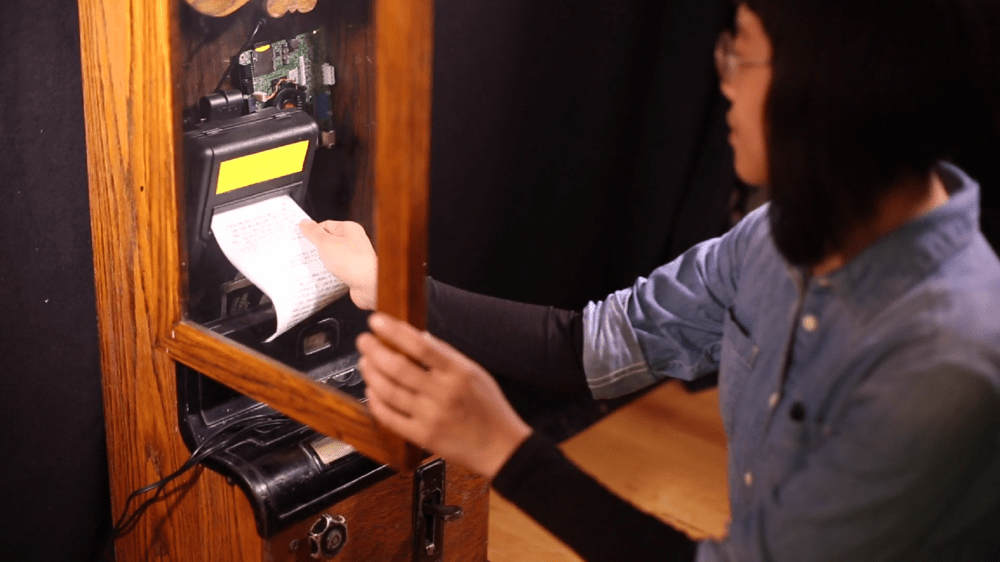

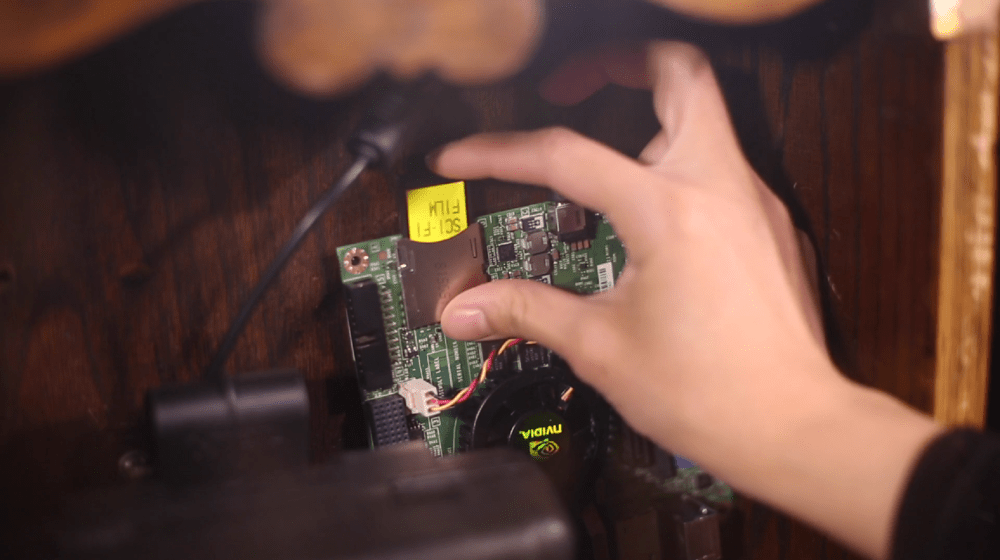

Thanks to Ross Goodwin for granting permission to illustrate this text with stills from videos presenting Narrated Reality (Clock) and word.camera (both 2016), two uses of artificial intelligence to build writing machines.