John Charles Thomas

The art lawyer outlines some of the legal issues raised by NFTs—and shares highlights from his own collection.

Last summer Alan Lau joined Animoca Brands, the Hong Kong-based venture capital and web3 gaming company, as its chief business officer. Prior to that he oversaw the development of a fintech insurance start-up at Tencent, and worked for almost a decade at the management consultancy McKinsey & Partners. Alongside this, he has become deeply involved in museums and contemporary art, as a passionate collector and patron. He is chair of the board of Para Site and vice-chair of the board of M+, both in Hong Kong, and heads up acquisition committees for Asian art at Tate in London and the Guggenheim in New York. Naturally, for someone who has long been interested in the relationship between art and technology, he also has an ever-growing collection of NFTs. Below he discusses how he got into art and then crypto—and compares his experiences of engaging with the two worlds.

I collected my first artwork maybe sixteen, seventeen years ago. I’d moved into a new office and I was looking for something for the wall. I imagine that people very rarely think, I want to be a collector when I grow up. Most people just fall into it, like I did. I wanted art that had a Hong Kong feel, so I ended up getting a piece by the graffiti artist King of Kowloon. That was the beginning of a journey which has been incredibly fascinating. Art gives you a different lens through which to look at our world.

Out of curiosity, I started going to biennials and art fairs. On one occasion at the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale, I met a group of people from Hong Kong. They didn’t understand why I was there, because I’m not from the art world. We got chatting and once they understood what I do, someone said: “Oh, it sounds like you would know how to read a financial statement. We could do with someone like that on our board.” So that’s how I ended up joining the board of my first art non-profit—Para Site, the oldest contemporary art space in Hong Kong. As I got to know more people, I became involved with other organizations, too.

By putting together a collection, you tell a story—from your vantage point, from your life experience, from the time and place you live in—that will hopefully provide an interesting context for people to understand the works. There are a couple of stories I am looking to tell with my collection. One is around Hong Kong, where I grew up, and China. The other is around technology, which relates to my professional work. Probably the oldest piece I have that references technology is by Nam June Paik, who started experimenting with TV sets in the 1960s. I’m interested in the way his work reflects a very optimistic view of the future, and of the relationship between humans and tech. Whereas more recent artists, like Jon Rafman, have a much more dystopian view of the world.

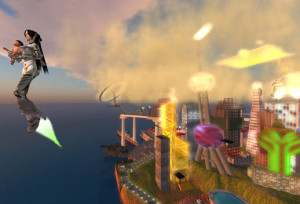

Another important piece in my collection is a video from Cao Fei’s RMB City, a virtual city that opened in Second Life in 2009. I was involved in that project artistically as I was nominated as the second “mayor” of the city. This was thirteen years ago, before anybody was talking about things like the metaverse and web3. But I believe the work really predicted the future, in a sense. We now exist in a world where we are constantly navigating the physical and the virtual, where both are equally real.

I started investing in crypto with friends in 2017, and then of course there was crypto winter, so I didn’t pay it much attention for a while. The first NFT I bought was a piece for 500 bucks from Pak’s Fungible Collection with Sotheby’s in April 2021. I thought it was pretty fun. So I bought it and then, like a lot of people in crypto, I just went down this rabbit hole. That was a defining moment. I also just think Pak’s practice is really interesting: It’s philosophical, it’s about economics, it’s game theory, it’s math, it’s digital art. I can totally see his work in a major contemporary art museum.

Pretty quickly I could see the product-market fit with NFTs. Because I’ve been close to the arts for so long, I know a lot of creators quite well, and I could see that this idea of what NFTs can do—a way to own your content and protect your digital property rights—was really transformational. I realized I wanted to be part of this movement. I started having conversations with artists and helping them to launch their NFT projects. After about a year I decided to turn that interest into my full-time role at Animoca, where as chief business officer I take care of investments and partnerships and also support our portfolio.

My own NFT collection has grown into a mix of projects. I hold some PFPs—Bored Ape, Cool Cats, etc. I’m also interested in contemporary artists getting into NFTs—I thought what Ian Cheng did with you at Outland was really innovative. I loved what Takashi Murakami did with CloneX and RTFKT. Of course, RTFKT have since been bought by Nike, and I think all the physical-digital drops they’ve been doing—like their “Back to the Future” sneakers—are super exciting as well. Another physical-digital combination I acquired is a “psychological portrait” canvas painting by Jason Boyd Kinsella, with an accompanying NFT which is not just a digital twin, but a standalone work.

The main difference for me between the traditional art world and NFTs is the community in web3. With Murakami’s NFT project—as opposed to his other non-digital work—you can go to Discord or Twitter and immediately find a community of fans who are all really excited about the artist and his creation. I’d never experienced that in the decade and a half that I’ve been involved in contemporary art. I think this is a key point whenever anyone says that an NFT is just a jpeg or something like that. I also think you really have to go through it, to immerse yourself in the conversation online, to experience it. Only then do you get a sense of how this is something totally different.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz