Lucid Dreamer

Sara Ludy’s art explores the often unnoticed points where physical, digital, and imagined spaces meet.

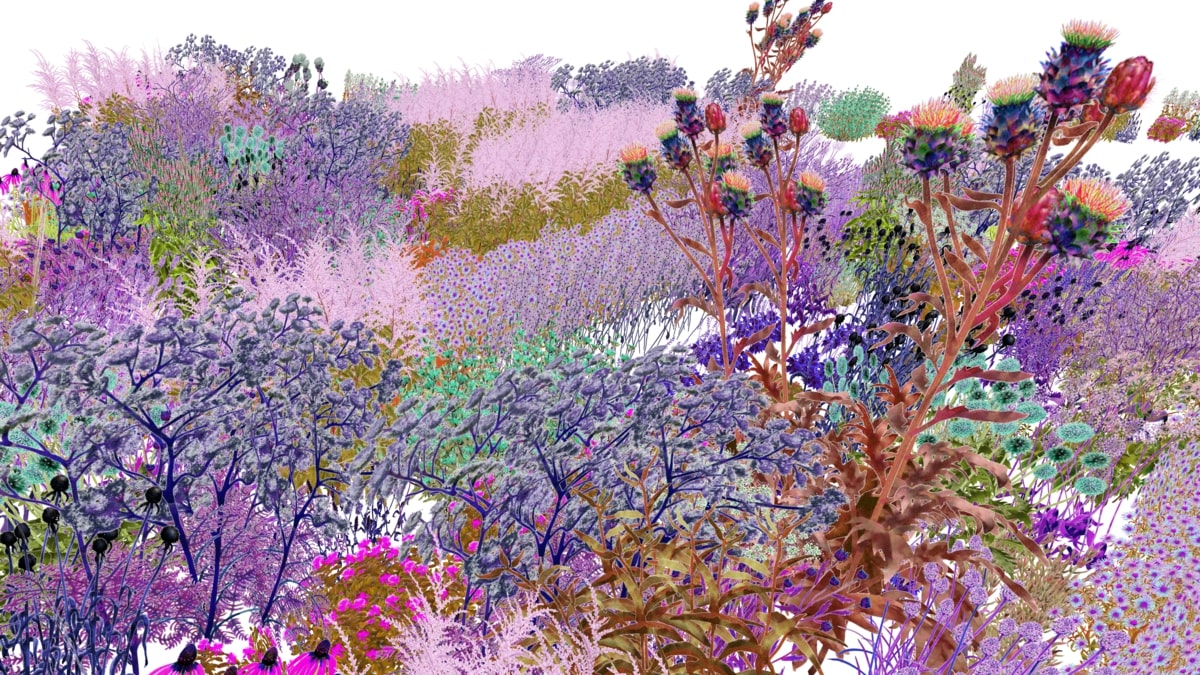

The Museum für Naturkunde, a nineteenth-century edifice on the busy Invalidenstraße in central Berlin, is home to the largest dinosaur skeleton in the world: a Brachiosaurus brancai that looms nearly 44 feet high. Over the past couple of months, a rather more vivacious exhibit has appeared in the forecourt of the museum. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s Pollinator Pathmaker is a garden—or, as the artist prefers to put it, a “living artwork”—designed using an algorithm. There have been two prior editions in the UK, at the Eden Project in Cornwall in 2021 and the Serpentine in London in 2022; this latest version was commissioned by the German LAS Art Foundation. More than seven thousand plants, from grass-like clumps of sedge to shrubs of lavender and coppery sneezeweeds, have been laid out across four separate beds. An uninformed visitor might easily mistake it for a trendy cottage garden: an informal planting style in which lots of different blooms are arranged in an intentionally haphazard way. But there’s nothing haphazard about this plot of land. The algorithm responsible for its lay-out was written to calculate planting schemes that support the maximum number of pollinator species in the space available. Taking into account factors such as soil and light conditions, it selects the plants from a region-specific list developed by the artist in consultation with horticulturalists and pollinator experts.

If you happen to like your garden, and all the butterflies fluttering about, that’s great—and beside the point.

The gambit of Pollinator Pathmaker is that this algorithm will prevent our aesthetic biases from affecting the design of the gardens. Per Ginsberg, the result is an “artwork for pollinators,” which humans are supposed only to implement and maintain. If you also happen to like your garden, and all the butterflies fluttering about, that’s great—and beside the point. Of course, this raises the question of whether a human is capable of judging an artwork for which they are explicitly not the intended audience. But while the lovely sights and smells of the garden are not for us, we are certainly equipped to understand the ideas, hopes, and fears that have brought it into existence.

In 2017, Ginsberg completed her PhD at the Royal College of Art in London. Entitled “Better,” the thesis explored how our dreams for the future shape the things we design and produce. Since then her artistic practice has focused on humanity’s relationship to technology and nature: the advancements (synthetic biology, artificial intelligence) that have been prioritized and the degradations (biodiversity loss, extreme weather) that seem to have been accepted as inevitable. For one piece, Machine Auguries (2019–), she trained neural networks to create an artificial dawn chorus, replacing the songs of real birds being driven out of cities by light and sound pollution. Essentially, Ginsberg’s work asks: Why is Silicon Valley so obsessed with superintelligence, and ignoring the wildfires raging around it? Pollinator Pathmaker is an attempt to turn things around, harnessing tech for the benefit of nonhuman species. When we spoke, Ginsberg described the tool she developed in collaboration with the string theory physicist Przemek Witaszyka form of “algorithmic altruism,” “coded for empathy.” She wants other people to use it, too. Alongside the large-scale commissioned editions of the project, there is a website where anyone can design their own smaller DIY garden. LAS has initiated a campaign to get communities planting in every district of Berlin; so far five gardens, in a mix of schools and public spaces, have been set up. For an artwork that claims to take humans out of the equation, our responses are quite literally part of the enterprise.

Why is Silicon Valley so obsessed with superintelligence, and ignoring the wildfires raging around it?

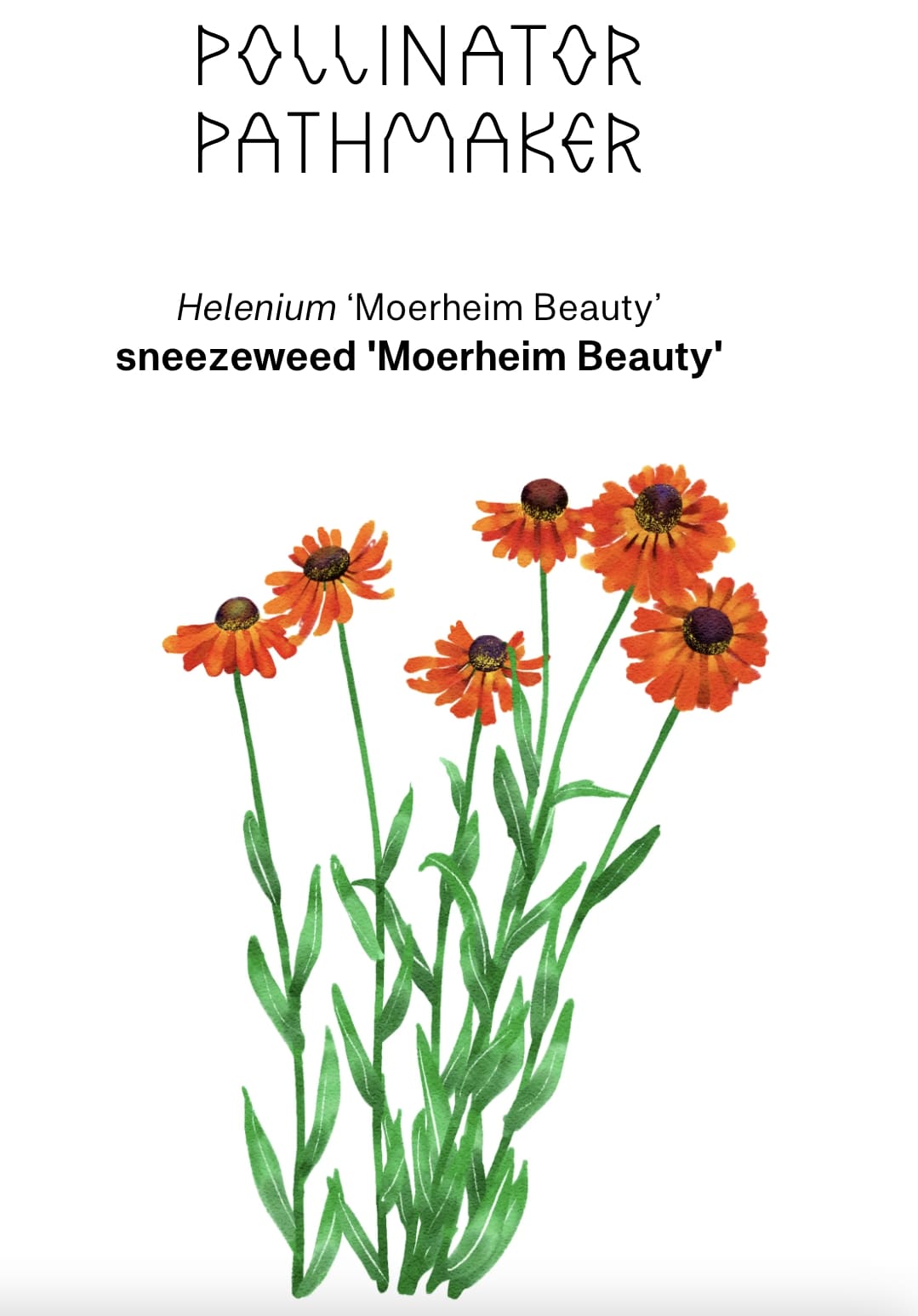

On a basic level, Pollinator Pathmaker is a pedagogical experience. Navigating the beautifully made and joyfully glitch-free site, you learn all about why and how the gardens are not designed for you. There are texts which relate the staggering decrease in pollinators—75 percent in Germany over the last quarter century—and their essential role in functioning ecosystems. Concepts such as co-evolution, which refers to the physical characteristics developed by plants and pollinators in tandem to aid reproduction, are elucidated. And did you know that cultivated varieties, bred for traits like scent, often result in less pollen and nectar? These, along with invasive non-native species, are therefore avoided in the regional “palettes” of plant options fed into the algorithm. Each of the commissioned gardens has its own page with a list of the plants that were selected for it: click on one, and a new window will pop up with a digital painting by Ginsberg of the species, as well as some information about the pollinators it attracts and the environmental conditions it requires. Then, if you decide to use the garden-design tool, you can choose between layouts that appeal to the two foraging styles of pollinators: patches and paths. “Beetles explore patches more randomly,” writes Ginsberg, “while bees and some other insects remember the locations of the flowers they visit.” Finally, once your garden has been generated, you can turn on a feature called “pollinator vision,” which alters the palette to show how different insect species see different parts of the color spectrum. We might appreciate a vibrant splash of red, but to bees it’s indistinguishable from black. They do, however, love purple, because it’s toward the ultraviolet end of the spectrum.

But this is not just a science lesson. It’s also a philosophical exercise, asking us to reassess our preferences and behaviors when it comes to art as well as technology and gardening. At the press conference for the unveiling of the garden in Berlin, Ginsberg made a tongue-in-cheek reference to her project as an “anti-NFT.” If minting digital art on the blockchain is a way to ensure nonfungibility, the algorithm in Pollinator Pathmaker is meant to be shared freely and widely. The point here is less about opposing NFTs specifically than about calling into question the general market logic of value in scarcity. While an art collector might prefer if Ginsberg produced a limited-edition print or NFT of one of her digital plant paintings, the pollinators have different interests—and so she is unlikely to oblige. Her stated goal is to turn Pollinator Pathmaker into “the world’s largest climate-positive artwork”: alongside the DIY garden campaign, prospective institutional or private partners are invited to get in touch to commission further full-scale international editions. Hours before the press conference, it was announced that the project had won the European Commission’s 2023 S+T+ARTS prize in the category of artistic innovation, so don’t be surprised if more gardens begin to spring up around the world. (The gardens at the Serpentine and the Eden Project are permanent, although unfortunately the LAS edition will only be maintained until November 2026, after which the plants will be relocated.)

Ginsberg is aware of the irony of environmental activism that seeks to decenter humans when, in the long run, our species will count among its beneficiaries. Her works often invoke beauty and sublimity, whether of flowering plants or birdsong—aesthetic categories that foreground our inevitably human perspective on the natural world and what will be lost if the trajectory of the climate crisis is not reversed. I am reminded of the episode of “Friends” in which Phoebe tries and fails to prove that we are capable of purely selfless acts—in the process, she lets a bee sting her, and is devastated to realize that this means the bee will have died. Fighting for the survival of other species means fighting for our own survival, too. If you need a picture of what extinction means, just look at the dinosaurs.

Gabrielle Schwarz is Outland’s deputy editor.