The Hirsch Truth: Episode 8

Ann takes a look at the first chapter of Annka Kultys Gallery's exhibition “Web 3.0 Aesthetics: In the Future Post-Hype of the NFTs.”

This past fall, buoyed by NFT sales, Jonathan Chomko left home for a long trip. “Montreal in the winter is a dark and cold place, and I’m trying to realize my freedoms a little bit,” he told me over a spotty internet connection. Chomko was calling from California’s Sonoran Desert, where he has spent the past month at an off-grid tech-and-art community called Mars College. “The idea was to leave Montreal on a motorcycle and not come back until I could come back on a motorcycle,” he said. “It’s just a nice physical limit. I guess I like physical limits.”

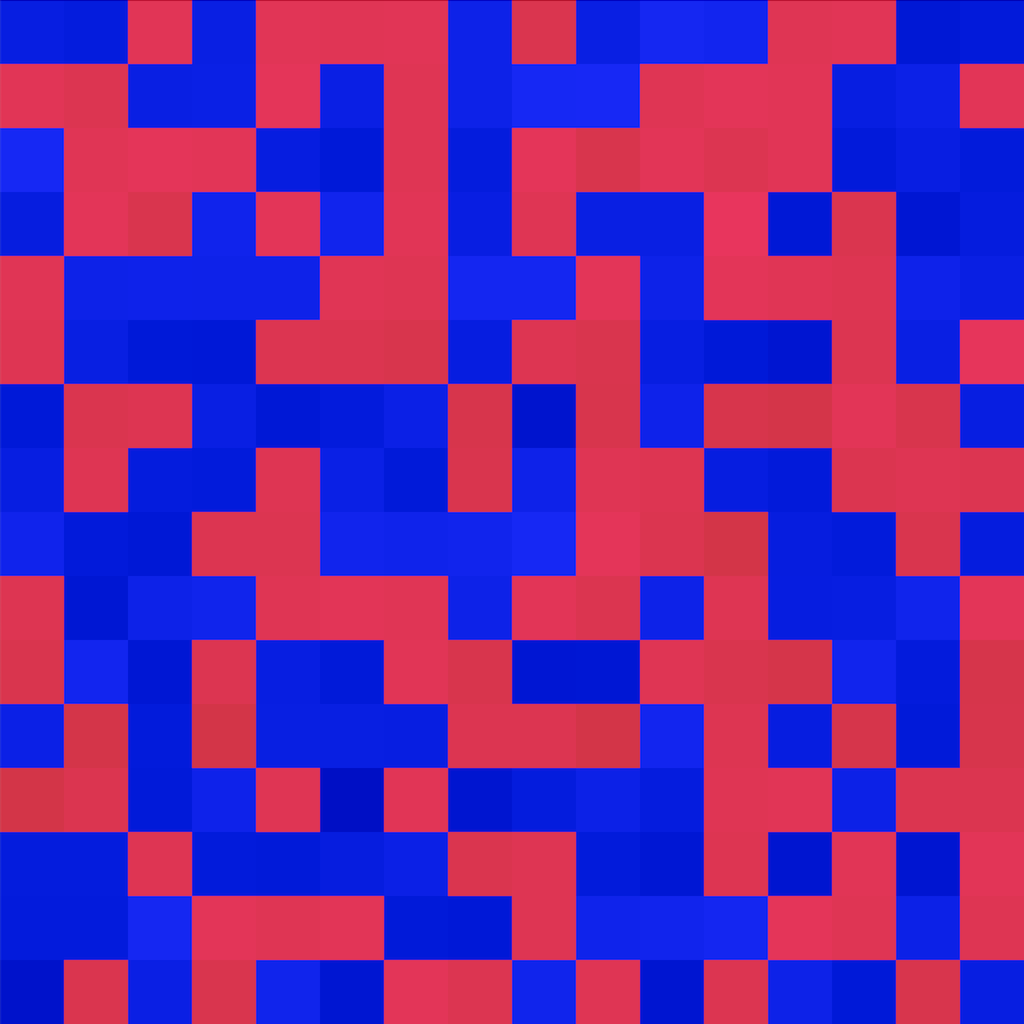

At 7:30 a.m. on the day before we spoke, Chomko climbed onto the roof of a building he helped construct and sat down at his production studio to complete another self-imposed assignment. He was creating the final installment of the fourth series in his ongoing NFT project, Proof of Work. For 13 hours and 31 minutes, under a tan canopy beside a few solar panels, he tapped at his phone… and tapped, and tapped—some 262,144 times. Guided by his openFrameworks software, each press added a single pixel to what would become a 512×512 grid; the pixels’ colors were randomly coded as red or blue, and the pressure with which he pressed modulated their hue.

Proof of Work reflects a progression in his work toward zooming in and paring down, from the streetscape to a cell phone to ultimately a single button.

Chomko had been doing one Proof of Work piece a day, with dramatically increasing effort. The first was a single pixel: one tap. The second was a 2×2 grid, then 4×4, time and effort quadrupling until he hit the limit for what he could complete in 24 hours, at 512×512. Examining this final image, you might see a few striations: darker or lighter sections where he pressed for a period with more or less intensity. Each piece has an accompanying video, too. Red and blue dots appear beside a close-up of his fingers and a wider shot of his torso, like you’d see on a Zoom call. Most NFTs, it doesn’t really matter where they’re made, but for this one the place stands out. In the video, Chomko’s face is deadpan under a wide-brimmed camping hat that’s slightly askew. Stretched out behind him is a vast and inhospitable landscape, endless desert under an open sky. It feels like there shouldn’t be a person there.

Chomko’s decade-long art practice predates his NFTs, but Proof of Work extends a thread he’s consistently been weaving through software-guided performance—a willful submissiveness to the controlling influence of tech.

Shadowing, created in 2014 with Matthew Rosier, uses cameras and projectors hidden in city streetlamps to record and replay people’s shadows, which follow them a few beats behind, like a visual echo. After installing the project in a few different countries, Chomko noticed that passersby encountering their oddly behaving shadows often had similar responses: they’d put their arms out and spin like a helicopter or lie on the sidewalk to do a snow angel. “It was both the types of gestures that appear,” he said, “and the need to make larger gestures.”

Becoming increasingly aware of the repetitive behaviors in his own life, often brought on by cell phone use, Chomko created www.grindruberairbnb.exposed. In it, a small group of participants receives choreography in real-time through prompts on their phones. They perform by raising their hands to eye level and tapping where it says “Click here,” or staring at their screens while they pace around in unison, or in crisscrossing chaos. It’s sometimes done, by surprise, in public; a version in a metro station was accompanied by a live score by Yo-Yo Ma. The mood feels light, with the audience and actors prone to crack smiles, as if amused by how funny everyone looks.

That Proof of Work features Chomko as the sole software-guided performer is partly mere circumstance; the pandemic made public shows difficult. But it also reflects a progression in his work toward zooming in and paring down, from the streetscape to a cell phone to ultimately a single button. Likewise, the Proof of Work color palette could hardly be simpler: the first set was black-and-white, the second all-red, the third all-blue. Now, in the desert, it’s both colors. In the 2×2, they seem to form a horizon, blue sky over red sand. “I’m trying to see what is the least I can do to communicate something,” he said.

In this way, Proof of Work might evoke any number of conceptual works that point to the methods of their creation: Richard Long tamping down a path in the grass in A Line Made by Walking (1967), or Cory Arcangel’s Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations, which list specific software parameters in their titles so as to be theoretically reproducible with a single click. Proof of Work’s stated inspiration, however, was another NFT.

In an essay on his website, Chomko noted how after Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days sold for $69 million in March 2021, its buyer justified the price by calling attention to the 13 years worth of images collaged within it, saying, “the only thing you can’t hack digitally is time.” Working from this primitive definition of value, which conveniently leaves out aesthetics, Chomko devised in Proof of Work what he has called “minimum viable artworks.” The NFT acts as a container for content, and owners receive both the image and documentation. “None of those things is the thing itself,” Chomko said. “I consider the thing basically that time, whatever duration I spent doing the thing. You’re buying and speculating on a chunk of my time.”

It’s worth pointing out that buyers in the Dutch auctions for Proof of Work have basically priced all of the works the same, regardless if they took 7 seconds or 7 hours to create. In fact, the current highest-listed piece on the secondary market is one with a single pixel. More so than time, maybe it’s the joke people are valuing, and it works however you tell it. Proof of Work reveals the human touch in an otherwise inhuman work—and, frankly, in an often inhuman field, rife with overproduced ugliness and derivative generative art. In the documentation, Chomko remains almost neurotically straight-faced. The comedy arises from how unfunny it is: a man come down to the desert to do what, exactly?

Not far from where Chomko is staying in California is Salvation Mountain, an outdoor art environment turned roadside attraction that was built over the course of 30 years by an eccentric named Leonard Knight. Constructed from hay bales, adobe clay, and thousands of gallons of colorful paint, Salvation Mountain stands today as a monument to the arresting power of odd, hard-to-value work. Now that Knight has died and the place is slowly crumbling toward an inevitable return to the earth, it’s also a reminder of just how much consistent human input is needed to prop up man’s crazy schemes.

The comedy arises from how unfunny it is: a man come down to the desert to do what, exactly?

The Proof of Work contract, Chomko told me, allows for him to mint just a couple more sets to the series after this one. “I think the work that I’m doing is so far just medium exploration,” he said. “Exploring what this material is and what it does, and in what directions it nudges us. That’s just a stage with any medium, and eventually artists start making artworks that are less about the medium and just using the medium in ways it supports.” On his way to California, he worked on another collection, too, which he plans to mint later. Each piece is just two colors, a square inside another square, and aims to capture the feeling of different cities he passed through, places like Asheville and Terlingua, meaningful markers on a long, winding path.

Duncan Cooper writes about art and saints.