One Small Step Backward for Man

Pace’s Discord gives eager crypto speculators a taste of the art world's harsh realities: they go to the moon, you stay here on Earth.

I recently made a Twitter bot called “Disinterested Monkey Sailboat Association.” It tweets random names that are similar to Bored Ape Yacht Club, the popular collection of NFTs that feature drawings of cartoon apes. The code randomly picks an adjective, then an animal, then a vehicle, then a word for a group of people, and posts a new iteration every hour. Some recent examples are “Saucy Orca Glider Guild,” “Orderly Coyote Scooter Gang,” and “Quiet Cardinal Helicopter Squad.” My only goal in making the bot was to make myself laugh, and it worked. But the process of programming the bot and reading its tweets also made me think about the way that BAYC and other profile picture (PFP) NFT series combine bright, quirky imagery in a narrow, predictable form in order to promote a particular kind of commercial activity. It felt familiar, but I wasn’t sure how. Collectible designer toys come to mind, such as Kid Robot and Funko Pops, but that wasn’t it. Suddenly it struck me where the feeling of familiarity was coming from. It was the public art corollary to PFP NTFs: CowParade.

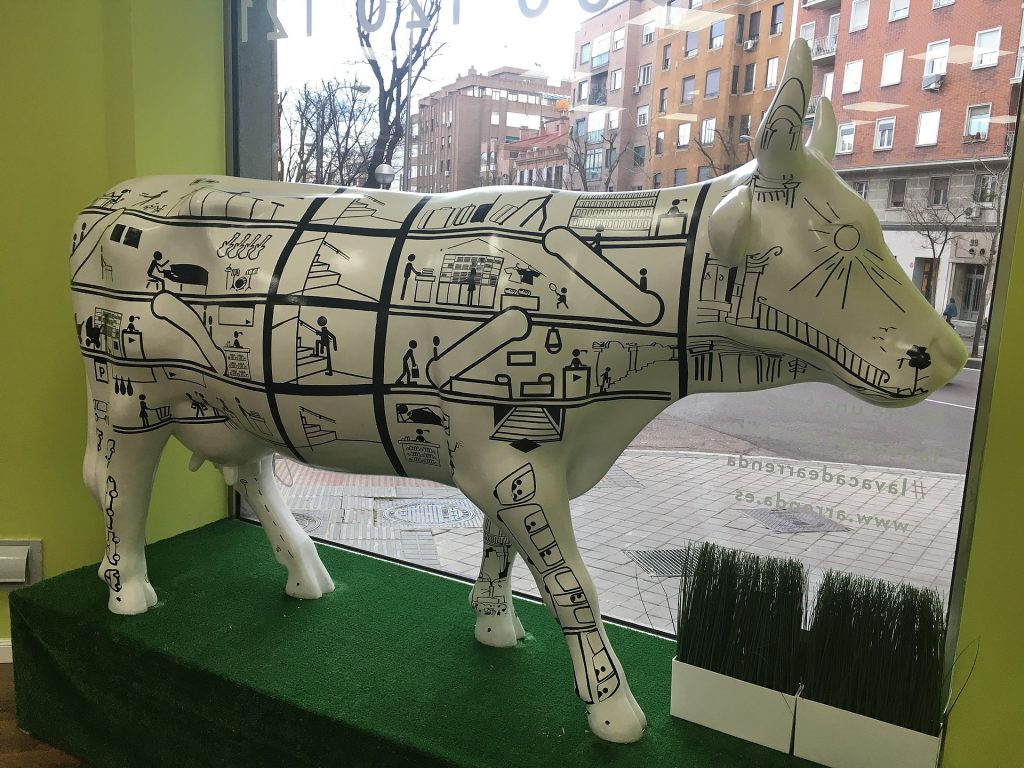

CowParade is a global series of public art exhibitions that began in Chicago in 1999, inspired by a similar project in Zurich, where dozens of local artists are invited to paint life-size fiberglass cows with their own unique flair. It spawned hundreds of imitators, and the most recent official CowParade exhibition concluded in New York last fall. CowParade is the ultimate example of a prescriptive public art project doubling as a civic marketing scheme. PFP NFT projects like BAYC share many qualities with CowParade, but the ape drawings trade city blocks for blockchains and street corner displays for social media avatars. PFP NFTs are anti-public art, leveraging playful riffs on cute characters not to boost foot traffic and commerce in a “cool city,” but to invite new users into the placeless, permissionless world of crypto citizenship.

PFP NFT projects like BAYC share many qualities with CowParade, but the ape drawings trade city blocks for blockchains and street corner displays for social media avatars.

It might seem that the opposite of public art would be private art instead of anti-public art, but NFTs are not private. PFP projects in particular are very much intended for public display as status symbols and identifiers of group membership. PFP NFTs are anti-public art because they reject not only the need for physical public space, they also forge a new kind of digital property ownership that stands in opposition to the open, “information wants to be free” internet of the past. The anti-public art of NFTs is visible to all, as images in IPFS storage and as smart contracts on a distributed ledger, but this visibility is a strategy for increasing the ubiquity and perceived value of the digital tokens that the images represent. Anti-public art rests on the idea that the only shared space worth creating is a community of owners of private digital property.

The cows wanted us to shop, but they didn’t take their love of free markets that far. Not surprisingly, the Zurich display that inspired the first CowParade in Chicago was staged to attract shoppers, and it was imported not by public art curators, but by a lawyer and the owner of a high-end shoe store. CowParade and its many imitators were part of a wider ’00s and ’10s trend of creative placemaking, the coordinated attempt to situate public art projects within urban revitalization efforts by “activating” otherwise underused city spaces. The hope was that residents and tourists would be drawn into urban centers to take pictures with the cows, then do some shopping and grab a bite to eat. These spillover effects are notoriously hard to measure, but it seems to have worked, judging by how many cities copied the idea.

The tactics and aesthetics of creative placemaking have improved over the past two decades, but CowParade’s one-size-fits-all approach to painting a city as cool, quirky, and approachable resonates with the PFP NFT boom of 2021. Like the lavishly painted cows, the apes, toads, and penguins filling up MetaMask wallets serve as emissaries for the digital city of crypto enthusiasts. If you want a picture with a cow, you have to bring yourself and your wallet downtown. If you want a rare digital avatar, you have to bring yourself and your digital wallet into the realm of cryptocurrency investment and exchange. In both cases, the art serves as an onboarding tool, a siren song that draws new participants into the economic activity that defines these environments.

The obvious difference between CowParade and PFP NFT projects is that the cows are physical objects displayed to enrich public—or at least publicly accessible—urban spaces. Even when the cows are auctioned off at the end of each exhibition, the proceeds benefit local charities, fulfilling the exhibition’s mission as a civic booster. NFTs, on the other hand, are built on the technical and ideological infrastructure of blockchain technology, a system of private ownership and exchange that is designed to evade regulation and taxation. PFP NFTs are mascots for a borderless currency that severs the ties between capital and place.

A few weeks ago I tweeted about how PFP NFT projects reminded me of CowParade, and someone responded with a typically anti-NFT comment saying that “at least the cows are not a pyramid scheme.” Reflecting on this, I realized that they’re both a little like pyramid schemes, although not in a financial sense. Buying NFTs is certainly financially precarious, and there are plenty of pump-and-dump scams, but they’re more like high-risk investments than pyramid schemes. The way the pyramid plays out—in both PFP NFT projects and CowParade imitators—is that the original concept is so successful and apparently simple to execute that hordes of wannabes line up to try their hand at capturing the cool factor of the original. Inevitably the law of diminishing returns kicks in pretty quickly. The Manatees of Jacksonville could never capture the magic of those first cows on Chicago’s Magnificent Mile, in the same way that Grouchy Tiger Social Club NFTs are unlikely to ever reach the status or floor prices of CryptoPunks or BAYC.

The Wikipedia page for CowParade lists one hundred similar exhibitions in North America, but I know that’s an undercount, because my hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, staged a version with fish that’s not on the list. The official CowParade website states that since the first Chicago exhibition the organization has held over eighty events, featuring the work of over ten thousand artists creating more than five thousand cows. That’s a lot of painted fiberglass animals, but these numbers pale in comparison to NFTs. OpenSea recently reported 2 million collections and over 80 million individual NFTs on their platform. Not all of those are PFP projects, of course, but many of the most voluminous collections are. CowParade and its imitators engage a broad swath of local artists, children, and corporate marketing departments to paint animal sculptures. PFP NFTs supercharge this multiplication of artworks by enabling individual artists or small teams to make thousands of unique artworks with a few dozen Photoshop layers and a few tweaks to readily available smart contract templates.

Both CowParade and PFP NFTs are best suited for artists who play by the rules, operating within well-defined structures.

The gold rush for PFP NFTs has created a cottage industry of people building tools to enable more and more artists to instantly produce thousands of unique, sellable digital artworks in an instant. A YouTube channel called HashLips NFT contains hours of video tutorials with titles like “Generate 10,000 NFTs,” “The NFT that makes you money,” and “Generate 10,000 NFT Poems.” The videos are very informative, but with over 46,000 subscribers, what does it mean when that many people each start cranking out 10,000-piece art projects, with the expectation that they’ll sell each unique digital picture? If each HashLips subscriber managed to make their own 10,000 piece NFT collection, that would yield 460 million new unique NFTs, which wouldn’t do much to support the idea that these digital goods are rare. A few weeks ago on Twitter Jon Ippolito posted a screenshot from Fiverr, noting that he found 18,000 freelancers willing to illustrate NFT projects, some with rates as low as $10. He added, “This isn’t democracy for digital creators. It’s a creative underclass underpinning a speculative market based on buying works with almost no grasp of who the artists are or why they make their work.” The glut of BAYC wannabes form the base of the pyramid of desire and perceived value, where they do little more than contrast the rarity of the handful of sought after PFP collections.

Up to this point I haven’t given much attention to the actual appearance of either the fiberglass cows or the PFP NFTs, and there’s a reason for that. In both cases, the scheme to produce dozens or thousands of similar artworks with slight variations is more consequential and interesting than anything an individual artist could do within that scheme. The enduring legacy of CowParade is its concept as a civic marketing strategy. Any artist painting a cow, however skillfully, is ultimately just along for the ride. PFP NFTs with random attributes selected by code and multiplied by the thousands is a compelling concept, but it’s difficult to add anything fresh to the form now that it has been established. Both CowParade and PFP NFTs are best suited for artists who play by the rules, operating within well-defined structures. This is why so many PFP projects, even those that are aesthetically pleasing and financially successful, start to seem like white noise as the form proliferates. Though it is not a new practice, making art with code still offers artists the opportunity to radically rethink the formal, aesthetic, and conceptual foundations of what an artwork can be. Good artists can make great work inside narrow constraints, but my hope is that when artists enter the new digital town squares of a blockchain-infused internet, they invent more radical strategies than simply painting a cow.

The banner image shows three tokens from the Holy Cows PFP NFT series and a modified photograph of Double Cow from Lima, Peru’s CowParade in 2010, taken by Santiago Stucchi-Portocarrero and released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Kevin Buist is a design strategist, curator, and writer based in Grand Rapids, Michigan.