Third World Futurism

Rimbawan Gerilya uses digital imaging tools to depict speculative futures from a Southeast Asian perspective.

“I think it’s tough to be alive now. I think societal collapse is in the air, it smells like it.” This should have been a line from a Brodsky poem. It smacks of Nietzsche on the old world dying for the new one to be reborn. But it was Timothée Chalamet at this year’s Venice Film Festival, talking about the pressures of living with social media and his new coming-of-age film in which he plays a cannibal. Crypto Twitter was aflutter about the Ethereum Merge, which finally came after a long hot summer of melted railway lines and various other escalating environmental catastrophes. On the Tezos blockchain, where no clear heir has emerged to the formative marketplace Hic et Nunc, drama rose with the heat. Many prominent artists raised questions about the Tezos Foundation’s collecting practices under curator Misan Harriman. The bear market continued. Futurity itself seemed to be in the balance; if the world ended soon enough, the idea of blockchain posterity wasn’t really viable anyway. The web3 community was a No Future Future Club, at once deeply invested in the forthcoming possibility implied by the technical advances of the blockchain and unsure about the long-term existence of a market or a world where those advances would matter. It was a fevered, melancholy summer of comingled doubt and profusion.

What does a composition for a perilous time look like?

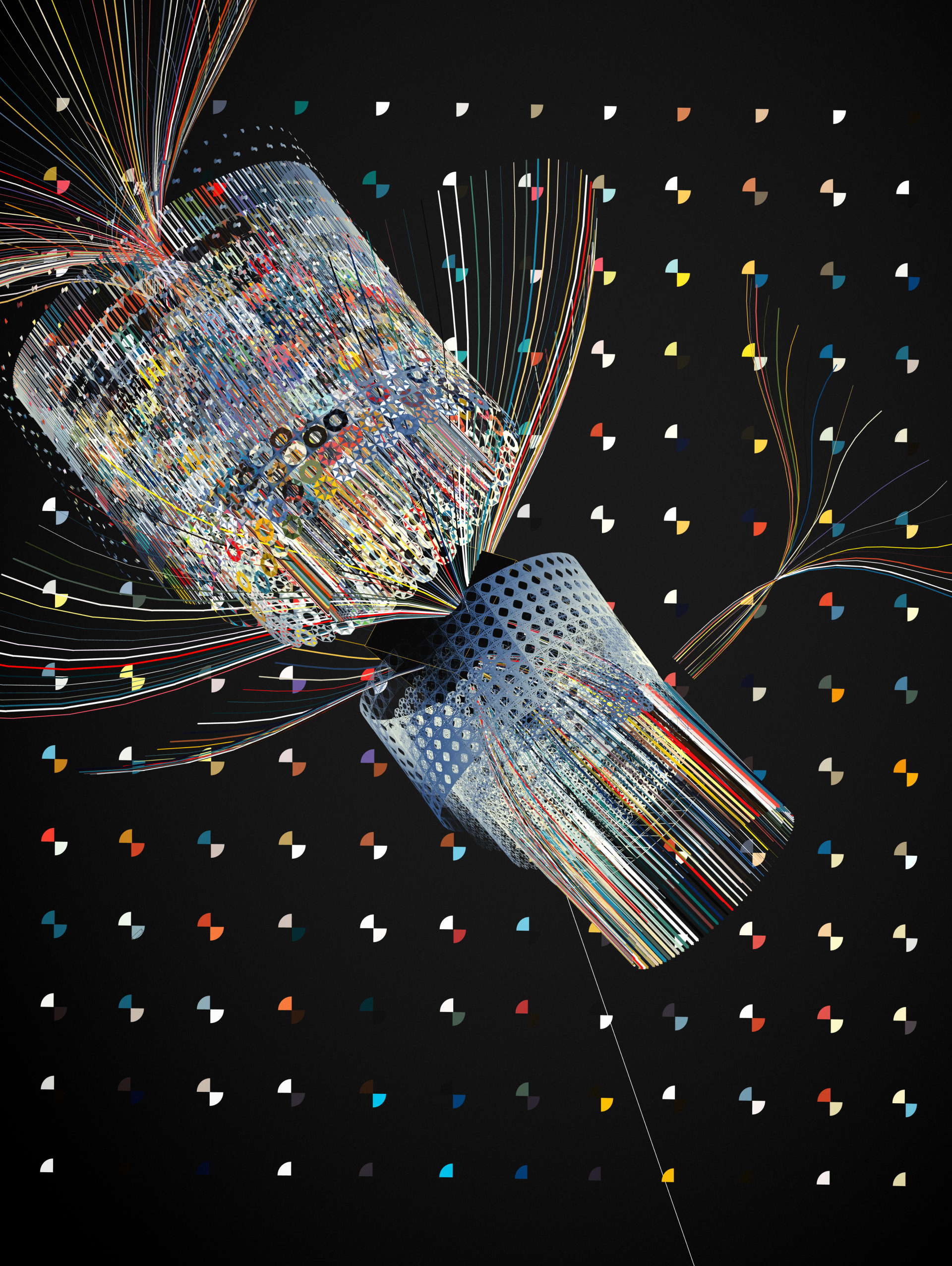

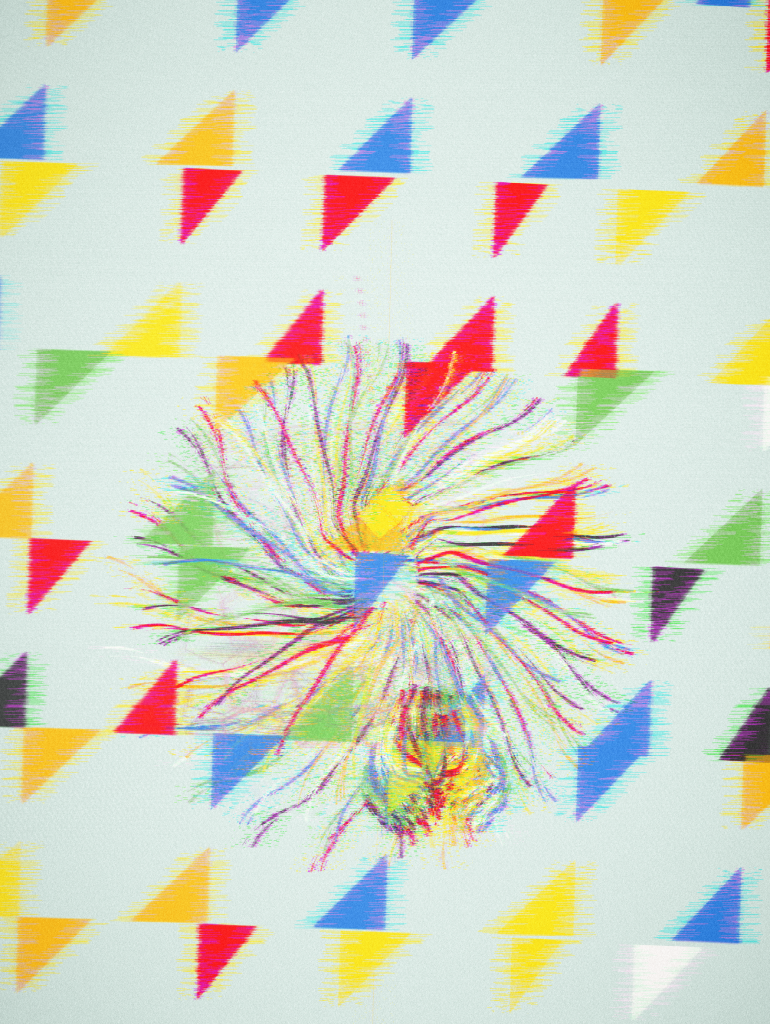

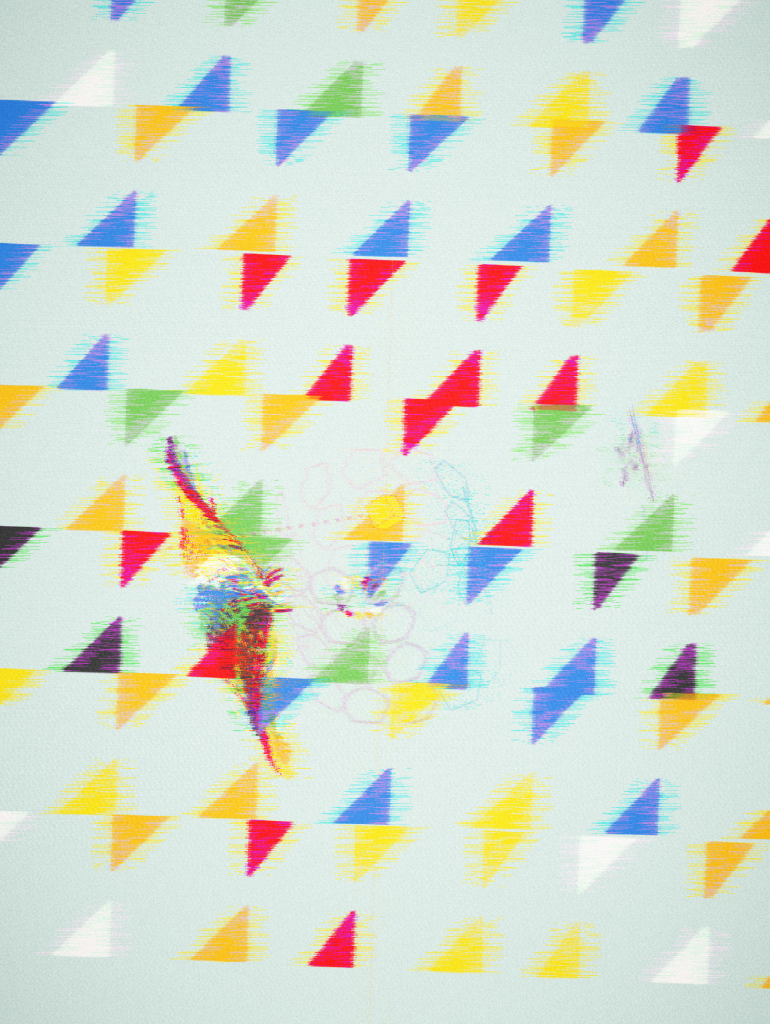

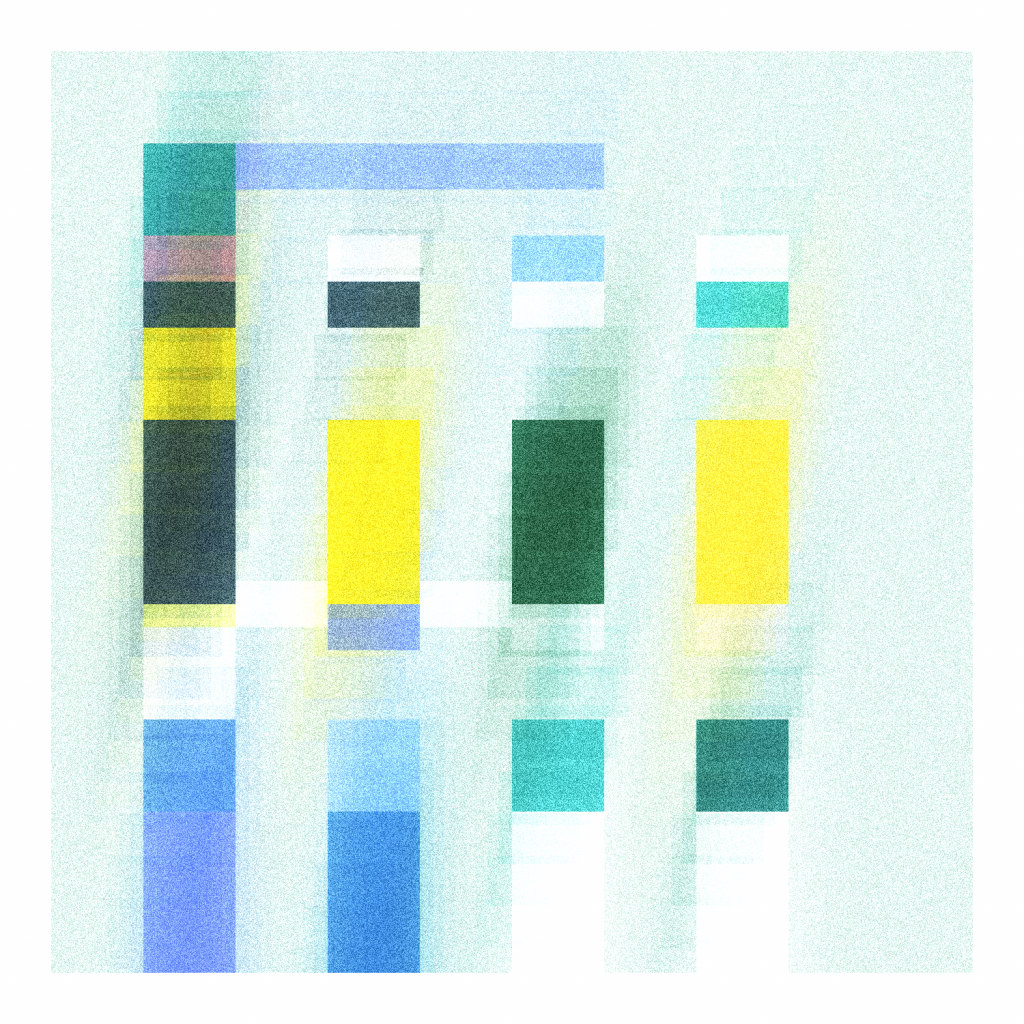

Amid this fray emerged a surprising, quietly thoughtful new work on Tezos-based NFT marketplace fxhash, proving that at least for now, the use-case of art alone might be enough to sustain the Tezos blockchain after Ethereum’s shift to a proof-of-stake protocol has eliminated one of Tezos’s competitive advantages. Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez and Andreas Rau’s Toccata (2022) is an audiovisual composition based on ideas of cyclic eternity. The piece changes by the day; the quality of the music and the generative geometric abstractions deteriorates over varying cycles that span days, weeks, and months. The work comprises 433 mints—a number clearly chosen in tribute to John Cage, whose ORGAN2/ASLSP is the longest piece of music in history, being played at a German church in a performance that began in 2001 and will last until 2640. Each mint of Toccata could run forever, and you can input a date into the browser bar to see how it will look and sound well into the future. I checked on one’s state fifty days, five years, and five hundred years from the present. It persists, each time aurallyblooming and then decaying into a reverb-static fuzz to match the state of its visual imagery.

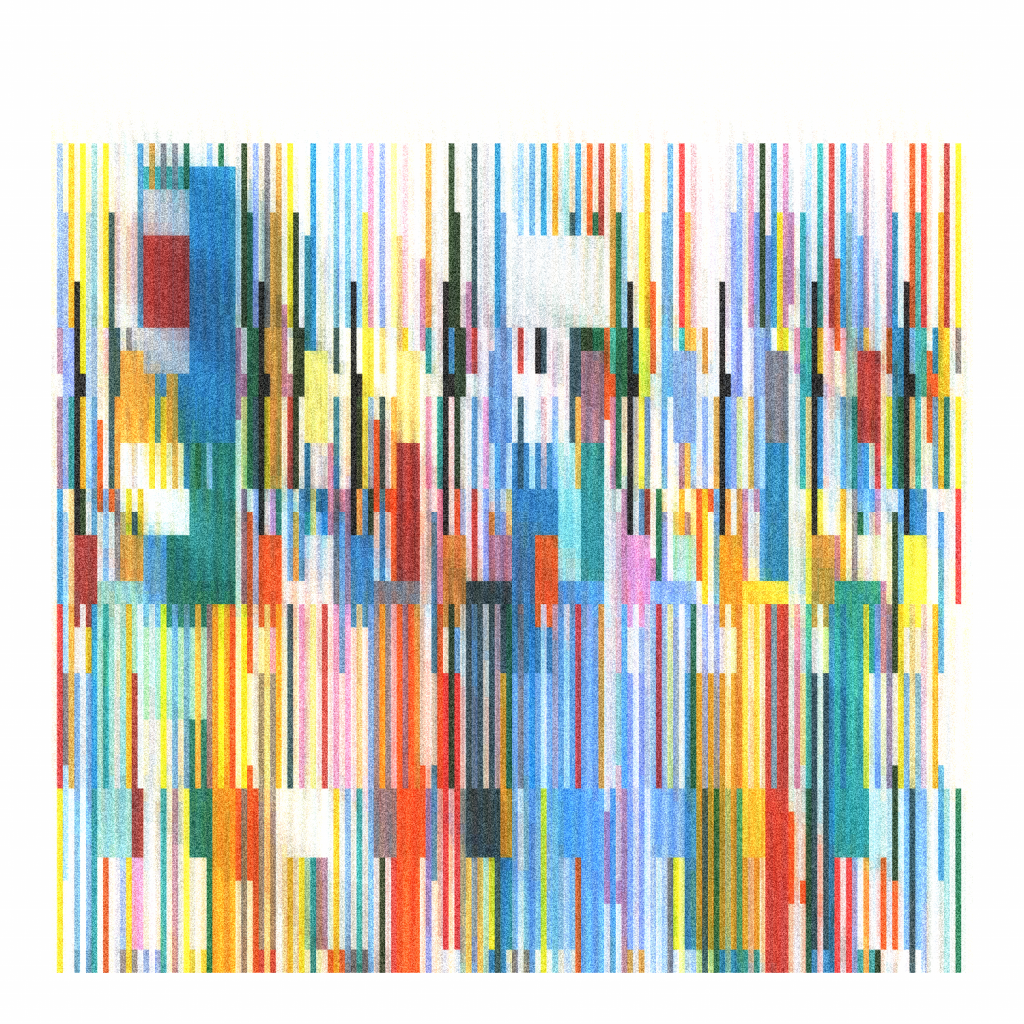

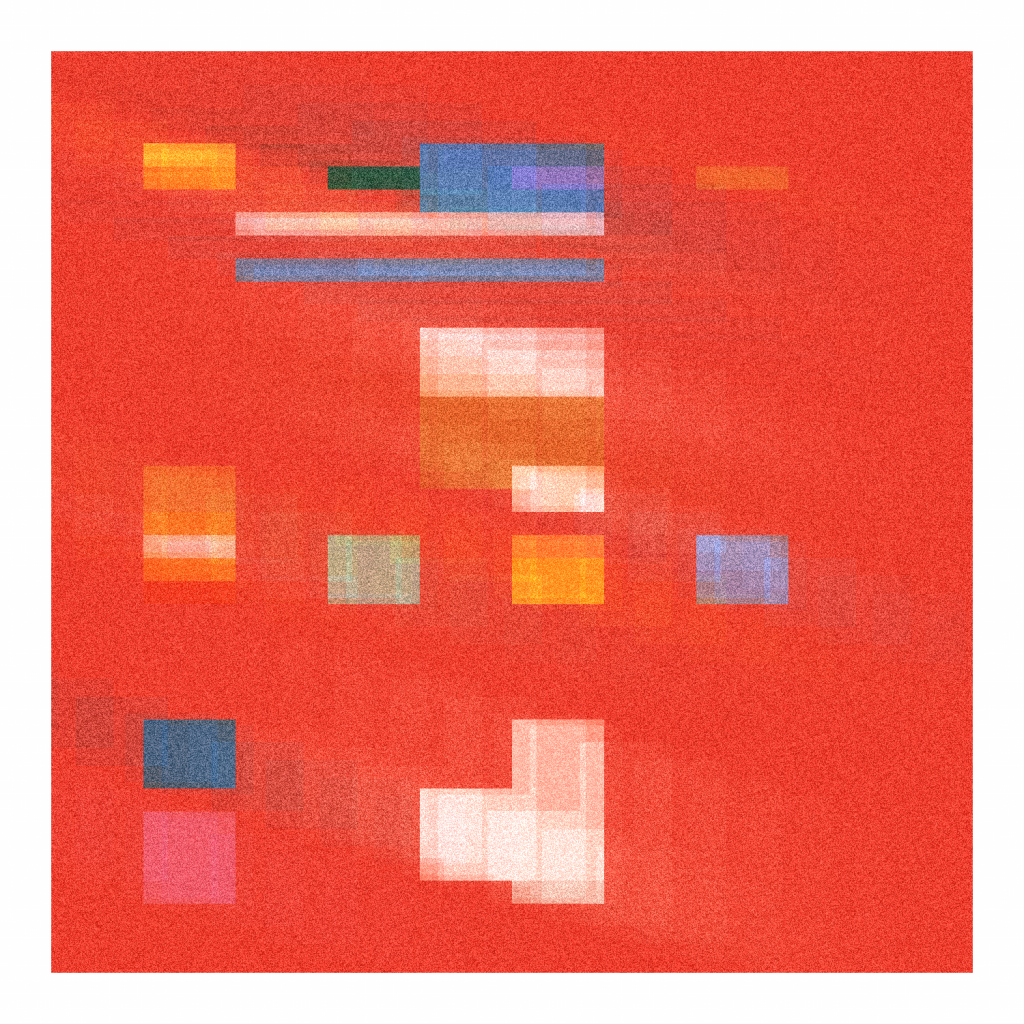

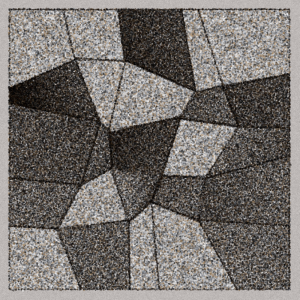

Toccata’s music samples variations on Sergei Prokofiev’s Toccata in D minor, Op. 11 (1912), which Rau composed and recorded on his childhood piano rather than using MIDI tones, which can sound a bit cold and removed. Given that toccata is derived from a word meaning “touch,” the actual hand-playing of a keyboard matters here. While the variation as form is in some sense a precursor to all generative art, especially considering the mathematically inflected baroque legacy of the fugue, the music of Toccata is not generatively coded. Rather, each mint applies effects of decay and regeneration to a specific segment of the recording. The images are fields of sieves, cubes, Xs and Os, and expanding fine lines evoking elegant jellyfish. The palette feels somehow West German, with warm orange-reds and vivid greenish yellows, while the geometric elements suggest a kind of cosmopolitan postwar futurism that also looks to the Bauhaus past. That could also be interpreted as a reference to Russian Constructivism, with crisp edges against white. This loosely suits the historical context of the Prokofiev score, another time of societal collapse and potential re-flowering.

The idea of a work of art encompassing multiple media is uncommon in the field of generative art NFTs, which have been primarily visual.

Prokofiev was a dubious and troubled revolutionary, considered at the forefront of Russian nationalism outside the country even as his repatriation in 1933, after fifteen years abroad, involved a more complicated relationship to the Soviet government. He produced propaganda for the Stalinist regime even though he sometimes came into conflict with it. Prokofiev is often seen as trying to innovate a uniquely twentieth-century response to the old “bourgeois” forms of musical production—symphonic suites, opera, and ballet—through their combination into multiple media as a Gesamtkunstwerk. That term may be appropriate for Soria-Rodríguez and Rau’s Toccata as well. The idea of a total work of art, or at least one encompassing multiple media, is uncommon in the field of generative art NFTs, which have been primarily visual. Toccata’s temporality—running both within the specified time of a viewer’s observation and to infinity—adds another dimension. The work is so impressive because it juggles all these concepts at once while still offering a meditative viewing experience. If it is a Gesamtkunstwerk, it is a quiet one, running along the axis of time even when the viewer has already walked away, or there is no viewer left at all. Even if the world ends it might still be playing somewhere, on an open screen powered by the sun, looping into decay and birth phases again, indifferent to the revolutions and controversies of human time. What does a composition for a perilous time look like? Prokofiev’s works after the October Revolution are one answer. Toccata is another.

The NFT market often cannibalizes itself in the frenzy that follows a successful work. The stream of generative art pieces that tried (and mostly failed) to imitate the rigorous geometric simplicities of Dmitri Cherniak’s Ringers and the PFP craze that followed the Bored Apes are just two examples. This hype cycle takes a toll on artists as well as viewers, but in Toccata Soria-Rodríguez and Rau lean into their own unique strengths to avoid this common pitfall. Rau’s previous complex textural work, such as Concrete (2021), and Soria-Rodríguez’s own musically inclined play of color and form, as in his contrapuntos (2021), both clearly inform Toccata. But these earlier pieces are conceptually distant enough for the latest work to be unique. It has a refreshing newness of form in a field where little felt genuinely new over the months of swelter. The risk of Toccata in holding only to its own, nearly infinite, terms cannot be underestimated.

As for history, Toccata suggests that is cyclic, too. After each descent into staticky death, the variations re-emerge, over days, weeks, or months, as crisp and new. Prokofiev had the misfortune of dying on the same day as Stalin—March 5, 1953—all but guaranteeing a sparse attendance at his funeral. Rau and Soria-Rodríguez set the start date of Toccata’s loop cycle to the beginning of their own collaboration—March 6, 2022. Does historicity matter, making a sense of pastness for an uncertain future? Toccata implies that it does.

A.V. Marraccini is an art historian and critic based in London. She is the author of the essay collection We the Parasites (Sublunary Editions, February 2023).