Outland's Special issues of 2023

This year Outland invited leading figures in digital art to collaborate on a series of thematic issues.

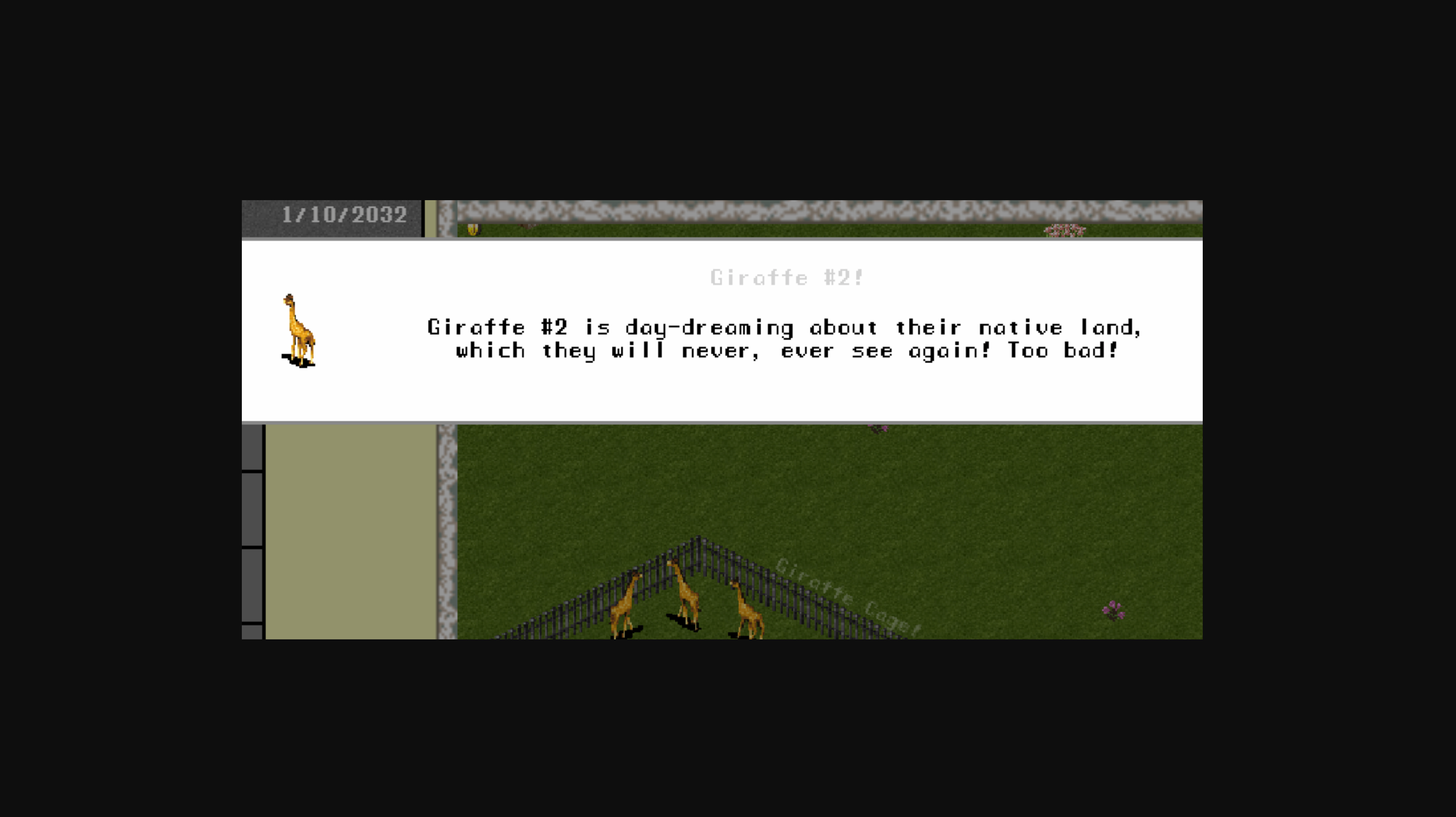

In the opening screen of Cassie McQuater’s art game Zoo Tycoon 2032 (2018), I’m faced with a choice: I can begin building my zoo, or I can hold a town hall meeting to gather feedback on the environmental impact of the proposed zoo. No matter which option I choose, I’ll ultimately be led to the same zoo-building gameplay.

With the game now underway, I eventually scroll to the edge of the zoo’s property line, where I’m greeted with the warning: “Literally everything past this point is on fire.” Best not to think about that, though! I’m here to play a zoo-building game, and by golly that’s what I’m going to do. So I return to the playable area and continue placing cages, animals, amenities, and staff. Zoo Tycoon 2032 is pretty full-featured for an indie art game. I lose myself deciding which animals look best adjacent to each other, and figuring out optimal placement of concession stands. I can do anything, so long as it’s “building a zoo.” I occasionally see notifications about the decimation of the local butterfly population, or some other ecological disaster caused by my zoo’s destructive footprint. But these are easily silenced, and to solve them would involve taking some action that does not involve “building a zoo,” and thus lies beyond the game’s scope. If I ever try to peer outside the zoo, by navigating to the boundary where my own sphere of influence ends, I again get the warning: “Literally everything else past this point is on fire.”

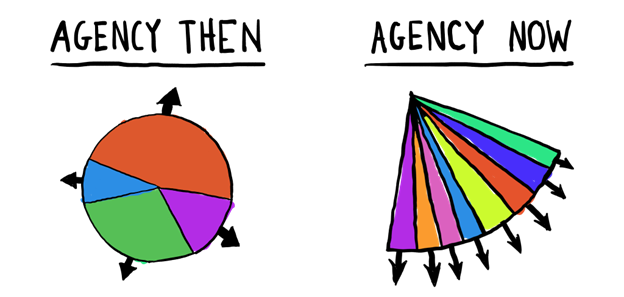

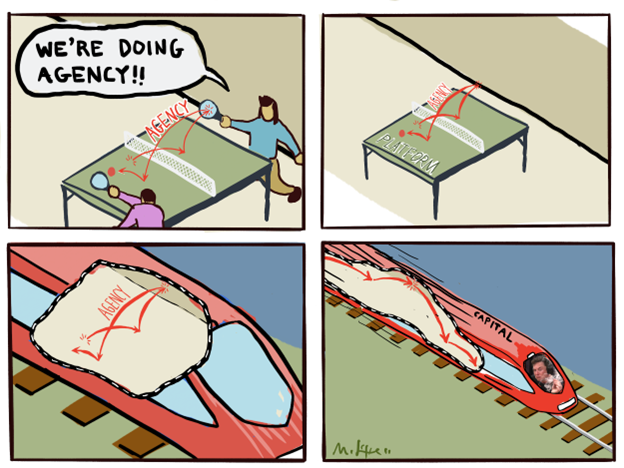

This is also how platform capitalism works! And it is a convenient allegory for a related condition that I will call the crisis of agency, whereby we are offered more and more choices, all of which funnel into a smaller and smaller possibility space of outcomes. In other words, we are presented with more choices than ever, which creates the illusion of agency. However, those choices are not created by expanding the range of possible outcomes, but by slicing up a smaller range of outcomes into infinitesimally small pathways.

I can go to the mall and choose from dozens of brands of phones, but no matter my decision, the effect on my life will be more or less the same: I will spend more time ignoring my kids while doomscrolling. Better yet, I can browse hundreds of different phones on Amazon, and again the effect will be the same: I will enrich Jeff Bezos and advance his specific vision of the world.

To quietly mold and circumscribe our agency is the key strategy of platform capitalism. This strategy has been implemented to great success, and thus the crisis of agency is a dominant condition of the world.

If art has a duty, it is to render visible the conditions in the world which are ubiquitous but otherwise invisible. You see where I’m going here. If you want to make an artwork depicting a person, you would do well to use oil paint, a technology that, like human flesh, absorbs and refracts light, and can be pulled taut across the canvas or else left to hang goopy and liquid across it. If you wanted to make an artwork depicting the dominant conditions in which that person exists (that is to say, platform capitalism and the crisis of agency), you would do well to use a technology which is also capable of molding and circumscribing human agency. In other words: games.

If art has a duty, it is to render visible the conditions in the world which are ubiquitous but otherwise invisible.

C. Thi Nguyen’s book Games: Agency As Art (2020) offers a comprehensive examination of how games use the agency of the player as their artistic medium. A game designer, Nguyen argues, is not working in the medium of cardboard mats and plastic figurines, or in the medium of pixels and algorithms. A game designer is molding a player’s range of possible behaviors. A game designer is chiseling away certain possibilities, and polishing others to make them stand out. They are designing environments that encourage certain types of exploration and discourage others. They are creating the conditions for a broad, but limited, set of user-defined outcomes. In short, they are sculpting the player’s agency.

Nguyen goes on to describe the holistic benefits of participating in games. “Adopting an alternate mode of agency, at a game’s behest, is a way of learning about new ways of being an agent,” he writes. “Games can thus provide us with something very special: they can expose us to alternate agencies.” In other words, games “depict” different ways for engaging with our environments. Chess depicts an agential condition of thoughtfulness and planning; Doom Eternal (2020) depicts an agential condition of frantic, proactive engagement; Journey (2012) depicts a condition of exploration. They do this through figurines and pixels and algorithms, sure, but those technologies are all in service of the true artistic medium, the thing that is being manipulated to create this experience: the player’s agency.

Games “depict” different ways for engaging with our environments.

Most games use agency as their medium, but most games are not also artworks. A common technique in art is to deliberately provide space for contemplation outside of the direct experience of the thing. Martin Creed takes visibility away from us in work no. 207: The lights going on and off (2000). Nam June Paik lets us watch the watcher in TV Buddha (1970). In Las Meninas (1656), Velazquez won’t even show us the damn painting. Now extrapolate this definition of an artwork to what we’ve just learned about games and their agential medium.

That moment when I scrolled to the boundary of the zoo in Zoo Tycoon 2032 revealed the game as an artwork. It explicitly acknowledged the game’s boundaries, and thus gave me a perch outside the game from which I could contemplate how its logic is representative of, or homologous to, the external world. The developers of Skyrim (2011) or Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) don’t want you to ever find the end of their worlds. They never want to break immersion. In open-world games especially, the designer’s goal is not so much to open up the world as it is to create just enough choices and outcomes within the world that the player never thinks about leaving.

Contemporary art exists to render the invisible. And the dominant structures and boundaries that guide our agency, constructed by the most powerful economic forces in history, are incredibly important invisible structures to render. An art game helps us to think about how we express our agency. An art game helps us identify the boundaries of our agency. An art game helps us think about what external factors are shaping that agency. It can do all these things because game technology creates homologous representations of the world. Game technology also sculpts a player’s agency, but employed as art, it also offers the player a space to realize and reflect on that manipulation.

An art game helps us to think about how we express our agency.

Art games exploded in 2023. Hans Ulrich Obrist’s exhibition “Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age,” presenting games by Lawrence Lek, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, and may others entered its second year on view at Julia Stoschek Collection in Dusseldorf, and opened in a second location, at Centre Pompidou-Metz. The Zabludowicz Collection in London mounted an ambitious solo exhibition of games by the Chinese artist LuYang, and Gabriel Massan released a game on Steam that was also exhibited at Serpentine Gallery. I saw Jacolby Satterwhite brilliantly deploying game aesthetics and machinima in the Metropolitan Museum’s Great Hall. Those are just a few highlights.

This glut of art games was slow to arrive, but it’s easy to understand why. It’s hard to make a video game. It’s really hard to make a good one. It’s near impossible to make a good one that can also hold a mirror to the world in the way that a good artwork should. However, the barrier to entry has lowered significantly, as game engines like Unity and Godot became more user-friendly, and then lowered again as AI code assistants became available to amateur artists. This tooling has predictably led to an accordant rise in artists creating games.

But I think the bigger reason why more artists are creating games is not because new game technology makes it easier to program fantastic creatures and environments, but because the world has come to look more and more like a game. All around us, our varied tempests are contained in fragile teapots, all designed to ultimately funnel us through narrow spouts. This is how games work, too. Literally everything past this point is on fire.

Mitchell F. Chan is an artist based in Toronto.