Devin Kenny & Coleman Collins

How can new modes of exchange inform artmaking and activism?

What are the forces currently shaping the digital art landscape? What is it like to work across the worlds of traditional art and web3? And how are artists, cultural workers, and the wider public responding to the latest experiments with blockchain technology? These were the questions at the core of “Present Digital,” a discussion held on March 4 at this year’s edition of the Global Art Forum in Dubai, featuring Clara Che Wei Peh and Audrey Ou, and moderated by Chris Fussner. Ou is co-founder and CEO of TRLab, an NFT platform launched in 2021. She grew up around art—her family founded the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai—and is interested in the potential for web3 to increase popular engagement with the work of artists past and present. Peh is a curator and writer who organized this year’s edition of Art Dubai Digital. She is also a co-founder of NFT Asia, a community for artists which seeks to forge connections between the mainstream and crypto communities: since its beginning in 2021 has grown to more than 4,000 members. Fussner, founder of the multidisciplinary creative studio Tropical Futures Institute, curated the inaugural edition of Art Dubai Digital in 2022.

CHRIS FUSSNER I think one of the things that binds each of us together is the idea of bridging: connecting networks or connecting spaces in the art world. In particular, bridging the traditional art world with the digital.

CLARA PEH Definitely, everything that my work has been focusing on for the past couple of years is centered on this idea of bridging between different kinds of worlds. In 2021 I curated a show of art on the blockchain called “Right Click + Save.” We were fortunate enough to secure a space in the Singapore Freeport, which seemed like a fitting venue for the show, given all the parallels people were drawing between buying and selling NFTs and storing your art in a freeport.

I wanted to deepen people’s knowledge and understanding of NFTs and art, so one room focused on historic projects that had been built on or around blockchains—for example, Sarah Meyohas’s Bitchcoin from 2015, and Rare Pepes. Another space showcased digitally native works, including Andy Warhol’s 1980s digital painting Untitled (Flower),which was recovered from floppy discs in 2014 and sold as an NFT at Christie’s in 2021. The idea was to get people thinking about the speed of digital innovation, and questions about how you conserve digital art, or what it means to put a work on-chain. There were also newer projects, like Dmitri Cherniak’s Ringers (2021), an example of fully on-chain generative art.

Earlier this year, I curated “Proof of Concept” for Co-Museum in Singapore. The show reflected on what’s happened over the past year and a half, as conversations around NFTs have matured. It seems that within the space now we’re ready to talk more deeply about the technology—about what is being built, contested, and experimented with. We wanted to showcase the diversity of the ecosystem and pique the interest of visitors who might not have a deep relationship to blockchain or NFTs. One work we showed was Tyler Hobbs’s QQL (2022), which is a web-based interface that allows users to produce their own generative art. Instead of displaying individual outputs, we created an interactive set-up for visitors to experience and engage with the work.

Both these exhibitions focused on bringing conversations around blockchain into physical space, creating interactive and affective experiences beyond just viewing the work online. In 2021 I co-founded NFT Asia, which I now run in collaboration with ten artists. We noticed that there were very few platforms or conversations devoted to the wider Asian continent and its diaspora. This isn’t a new problem in the art world but with this new ecosystem we felt there was an opportunity to do things differently. Could we create alternative platforms and digital means of coming together to shift the existing power structures and create support for artists? Many of the artists in our community don’t necessarily have access to curators or have never been formally taught how to present or talk about their work.

AUDREY OU It’s great to be in conversation with you because even though on the surface it may seem like we’re working on divergent issues, at our core, we are all aiming to bring art to the forefront of conversations and engage more people in learning about it in various ways.

TRLab’s mission has expanded as we’ve grown, but the “TR” stands for “tabula rasa”: blank slate. When we launched in 2021 we wanted to really think about how to approach this new world. We focus on fusing web3 technology with fine art knowledge to pioneer the future of collecting and participating in art. That means we help artists and institutions use web3 to extend their missions and brands, and we enable collectors and enthusiasts to gain access to art and educational experiences. There’s usually a level of smart contract innovation involved.

We’ve developed blockchain-based projects with amazing artists, like Cai Guo-Qiang, who developed an interactive educational project called “Your Daytime Fireworks” to supplement his core artistic practice of working with pyrotechnics. Collectors of his Firework Packet NFTs learned about Cai’s life and art, and also the various factors—weather, location, safety regulations—involved in deciding when to set off their Firework Packet. Cai wanted collectors to experience the birth of the final artwork as an act of co-creation.

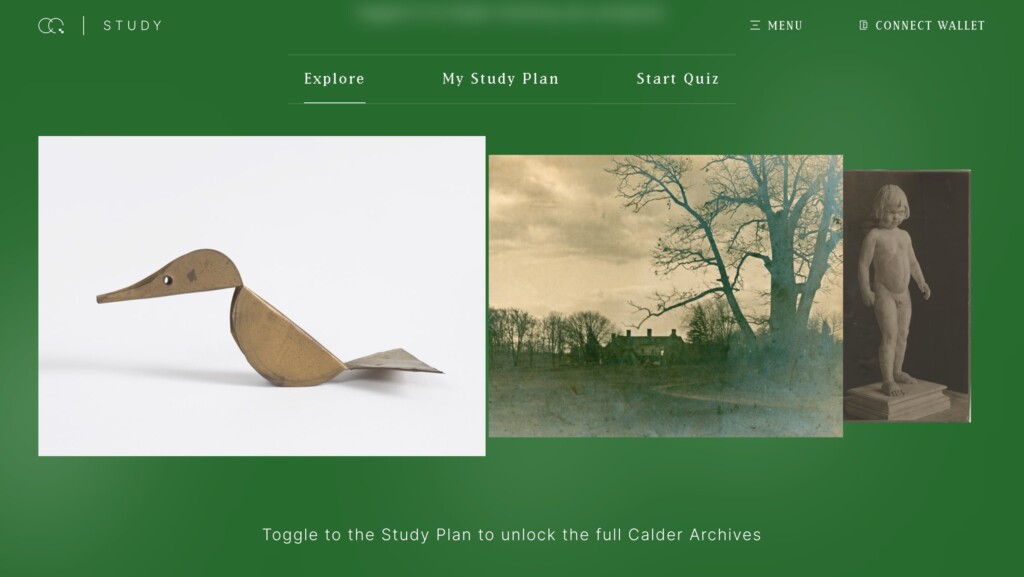

We are also working with the Calder Foundation, a non-profit devoted to the legacy of artist Alexander Calder. TRLab developed a blockchain-based art experience called The Calder Question, which is very near and dear to my heart. Sandy Rower, the president of the Calder Foundation, was initially skeptical about NFTs—he wasn’t interested in the potential financial revenue or anything like that. But he wanted to use web3 technology to find a way to encourage younger audiences and those who are curious about modern art to engage with Alexander Calder’s work online. So we created The Calder Question, a gamified digital educational portal and quiz that was designed to get people to spend time reading and learning about Calder.

The core of the gamified experience was a really tough quiz—one of my friends who is a curator thought she didn’t have to study before taking it, and she failed! But once you passed the quiz, you’d get a free NFT, which is a puzzle piece for an additional game that unlocks artworks, rewards, and other types of access to the Calder Foundation. More than 1,200 people took part. That was fascinating to us because it’s always been tough to figure out how to get people who would be willing perhaps to go to a museum but not read a book about art. I think web3 and technology can be put to important use in this regard.

FUSSNER “Bridging” is a term that’s used a lot in crypto—where you bridge from one network to another network. But it’s not an easy role to occupy because you’re between two spaces. You’re not pure crypto and you’re not pure trad art. What drives you to work in this space?

PEH I’ve thought about this a lot because, especially two years ago, if I said I work with NFTs then I would often be dismissed or my peers might regard my practice as being too commercial. But with NFT Asia, I’ve seen how many artists are genuinely looking to develop their practice and to break out of the systems that haven’t given them the luxury of infrastructural support.

I do agree with some of the traditional art world criticisms of NFTs, surrounding their ethics, politics, and sustainability, but if you’re not a part of the conversation, then how can you make change? My belief and my hope is that by getting involved, by being present at conversations like this, then I can help build a culture that I believe in. With NFT Asia, for example, we have created a space that we felt was missing but really crucial.

Similarly, in the digital section of Art Dubai this year, we’ve tried to switch things up and not just include traditional galleries but also look at collectives. How are artist collectives taking over in the space and what does all this mean? There’s so much that’s being challenged. Even the role of the curator is in question. That helps keep me personally in check. I’m always trying to ask myself what I’m doing, who I’m serving with my work, and what kind of alternative ecosystem we are building. How can we make sure it’s really different rather than replicating the existing issues in the traditional art world?

OU There’s something very scary but also wonderful about how nebulous the web3 space is—what terms and roles and new definitions are being worked out. What does it mean to be a curator? What does it mean to be a collector? That’s part of what attracts me to the space, because everyone is experimenting and there is no wrong way of doing things.

My work at TRLab is driven by two things. The first is the question of how legacy fades over time. This came out of a conversation I had with Sandy Rower, Alexander Calder’s grandson, when he asked me if I knew of Bob Dylan. I said that of course I did. So he said, “OK, name fifteen songs that Bob Dylan wrote.” And I couldn’t. He told me that he didn’t want, one hundred years from now, for a person to go into a museum and see a work by Calder and only recognize the form but not know the name of the artist or his significance. I am very passionate about using digital space to keep the legacy of artists alive.

Secondly, I’m really interested in how we can get people who have never truly engaged with fine art, or crypto-native traders who may think about art primarily as a financial asset, to look at it in a different way. For instance, I have a friend from college who got into Bitcoin very early. He lives in New York but has never been to museums or art-related events. I sent him The Calder Question and he took the quiz and scored one hundred percent. A few weeks later he texted me—he was passing through JFK and he had seen a Calder mobile. He sent me a picture. That was a really special moment.

Do I know what the future of this space looks like? Not really, but the present is exciting enough that I want to try to be part of the conversation to move the space forward and to move art forward.

FUSSNER Who cares about the future anyway, right? It’s all about the present. Despite this bridging, with any kind of technological adoption or diffusion there’s always exclusion as well—what you could call the digital divide. Not everyone is going to adopt new technology right away. Many of the new media artists I’ve known since before the NFT boom aren’t really interested. What are your observations in talking with different artists and practitioners in this space with regards to adopting NFT technology in their work?

OU When artists and foundations talk to us, we often urge them to think beyond reproducing and selling art as NFTs, because there are all kinds of other things you can do with proof of participation tokens or proof of education tokens. These are NFTs but not in the way people are thinking about them now.

I am less interested in things like fractionalizing or converting a physical artwork into an NFT project. I think there needs to be some sort of meaning behind the use of blockchain, such as interactivity that’s enabled by the blockchain—as in our project with Cai Guo-Qiang, and lots of other great projects out there. There needs to be a twist for traditional artists who haven’t previously used NFTs, to get them to come and experiment. We very much want to support them to do that.

PEH I’ve witnessed different kinds of divides, maybe because of the demographics of the artists I work and talk with. For example, you often see claims that web3 is borderless, but it very much is not. Artists in India, for example, are subject to regulations around trading virtual assets. I think the artists in the NFT space who are based in Berlin have a different reality, with the kind of environment and infrastructure that supports new media work as compared to an artist from Southeast Asia.

Also within the space, there’s a divide between artists who have had exposure to the traditional art world and know how to communicate their practice. Sometimes the way you put forward your work makes all the difference in terms of getting people to take you seriously versus them thinking “This is just a jpeg.” Part of this problem is because there aren’t enough curators or cultural workers like us supporting the space or taking these emergent practices seriously enough. It’s important to recognize these artists and their work.

—Transcribed and edited by Gabrielle Schwarz