The Redemption Wallet

Shezad Dawood invited collectors to sacrifice unwanted NFTs in order to participate in his own project. The result is a gallery of bull market mistakes.

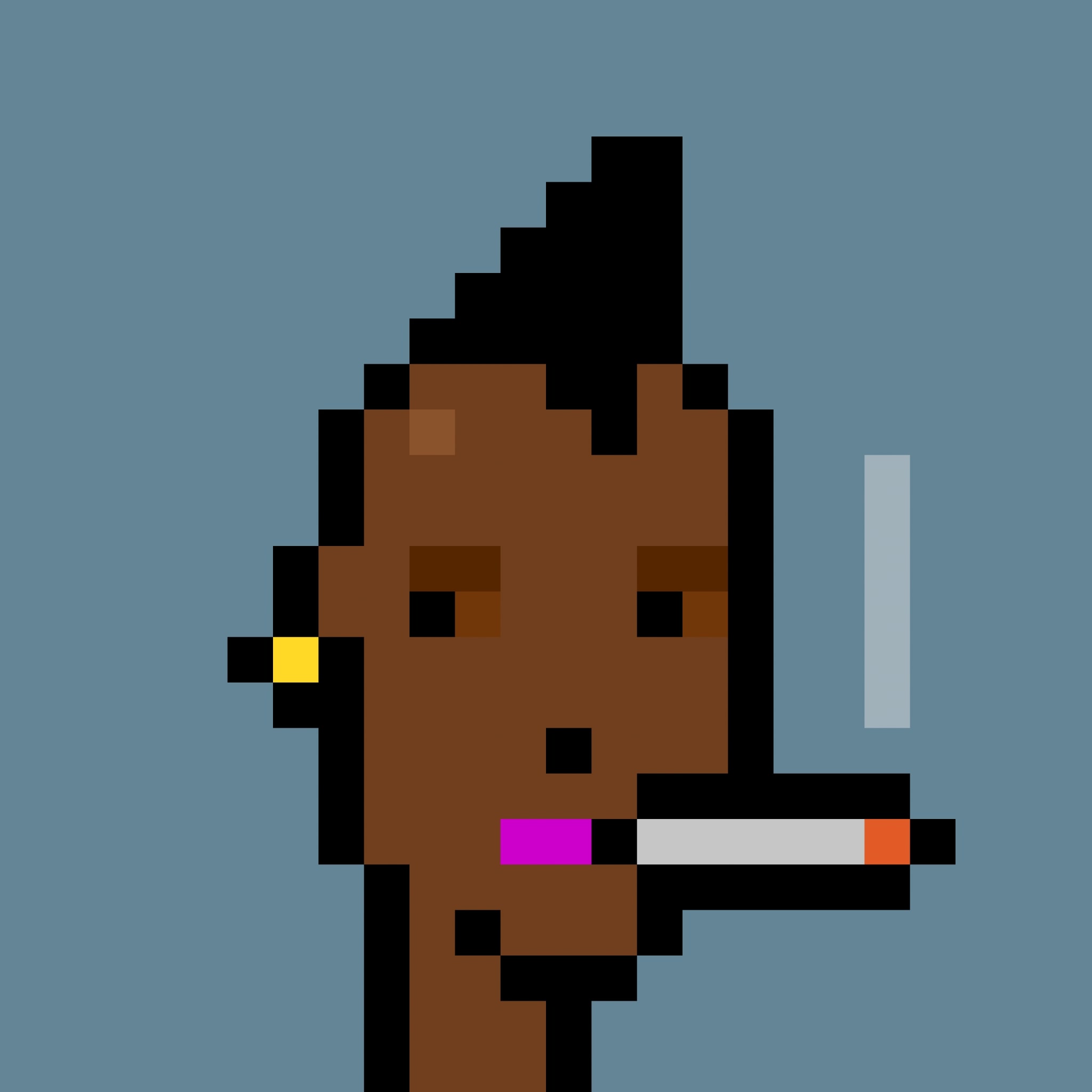

Earlier this year the Centre Pompidou in Paris announced a landmark acquisition: eighteen NFTs and blockchain-related projects by thirteen artists from France and beyond. The selection of works was intentionally eclectic, spanning from conceptual projects such as John Gerrard’s Petro National (2022) to a cigarette-smoking CryptoPunk. A display situating the works within the longer history of the dematerialization of art went on view last month. This move from a major French institution was surprising to some, but since its beginnings the Pompidou has been seriously invested in the collection and display of work made with new media—think, for instance, of “Les Immatériaux,” the famous exhibition of art and information technology curated by Jean-François Lyotard and Thierry Caput in 1985. Pompidou curators Marcella Lista and Philippe Bettinelli spoke to Outland about the evolution of the new media art collection for which they are both responsible, and how they assembled the grouping of works that has marked the museum’s entry into the world of NFTs.

Our media art collection began in 1976, one year before the opening of the Centre Pompidou. The idea was to place photography, film, video, and sound at the heart of this new home for the Musée National d’Art Moderne. In the 1980s, these various mediums were divided into three separate departments. Since then, the dedicated new media collection, which focuses on works made with digital technologies, has grown to include nearly three thousand works. Early on, the museum acquired some of the first closed-circuit video installations, such as Peter Campus’s Interface (1972), Bruce Nauman’s Going around the Corner Piece (1970), and Dan Graham’s Present Continuous Past(s) (1974). A pioneering closed-circuit piece by Peter Weibel, who died earlier this year, has also just entered the collection: Observation of Observation: Indetermination (1973).

From the 1990s onward, we have many interactive digital media works and artists’ websites. A key example is Chris Marker’s Zapping Zone: Proposals for an imaginary television, commissioned by the Centre Pompidou for the landmark exhibition “Passages de l’image” in 1990. In this work, Marker synthesized his early computer research, notably with the first multimedia software Hyper Studio. The work includes seven Apple 2GS computers, thirteen television sets, slides and photographic prints. The museum holds the entire archive of this work, making up nearly two hundred working disks. The last twenty years have been such an exciting period for further experimentation with technology, including through code and generative algorithms. We recently acquired David Claerbout’s work Olympia (The real time disintegration into ruins of the Berlin Olympic stadium over the course of a thousand years), a generative work that began in 2016 and is designed to last a millennium.

Over time we have worked to broaden the geographic remit of the collection, moving away from a strong Western focus towards non-Western art scenes—in line with the general direction of modern and contemporary art institutions all over Europe. NFTs are the latest addition to what is, in our collection of new media art, a global history of information technologies. It is within our collection’s DNA to study and represent relevant artistical uses of new technologies when they appear. One of our main priorities is to undertake this within the longer timeframe of a museum collection: in this case it meant waiting for the first wave of NFT speculation to pass before getting involved, and carefully selecting works that we thought would make sense in the collection in the long term; one specific aspect of French public collections is that works that enter them can never be sold.

It took us almost a year to research the selection, and discuss with the artists which works would be best suited for the collection. Some of the works have been donated, but other have been purchased by the museum. In each case, proposals have to go through the same procedure, which involves a curatorial committee within the museum, and an acquisition committee with appointed experts coming from outside the museum. Those steps take time, but they are there to guarantee that the museum makes the best decisions in the long run.

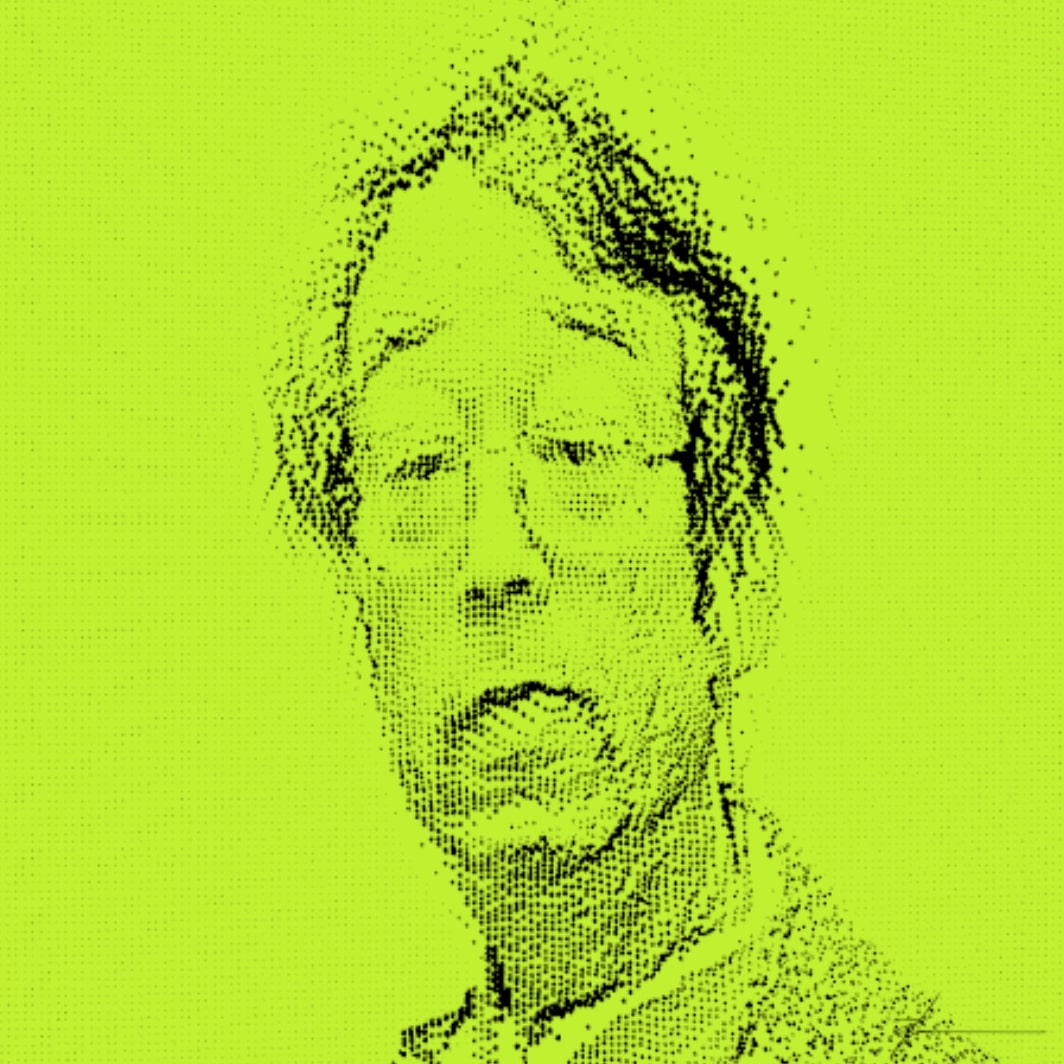

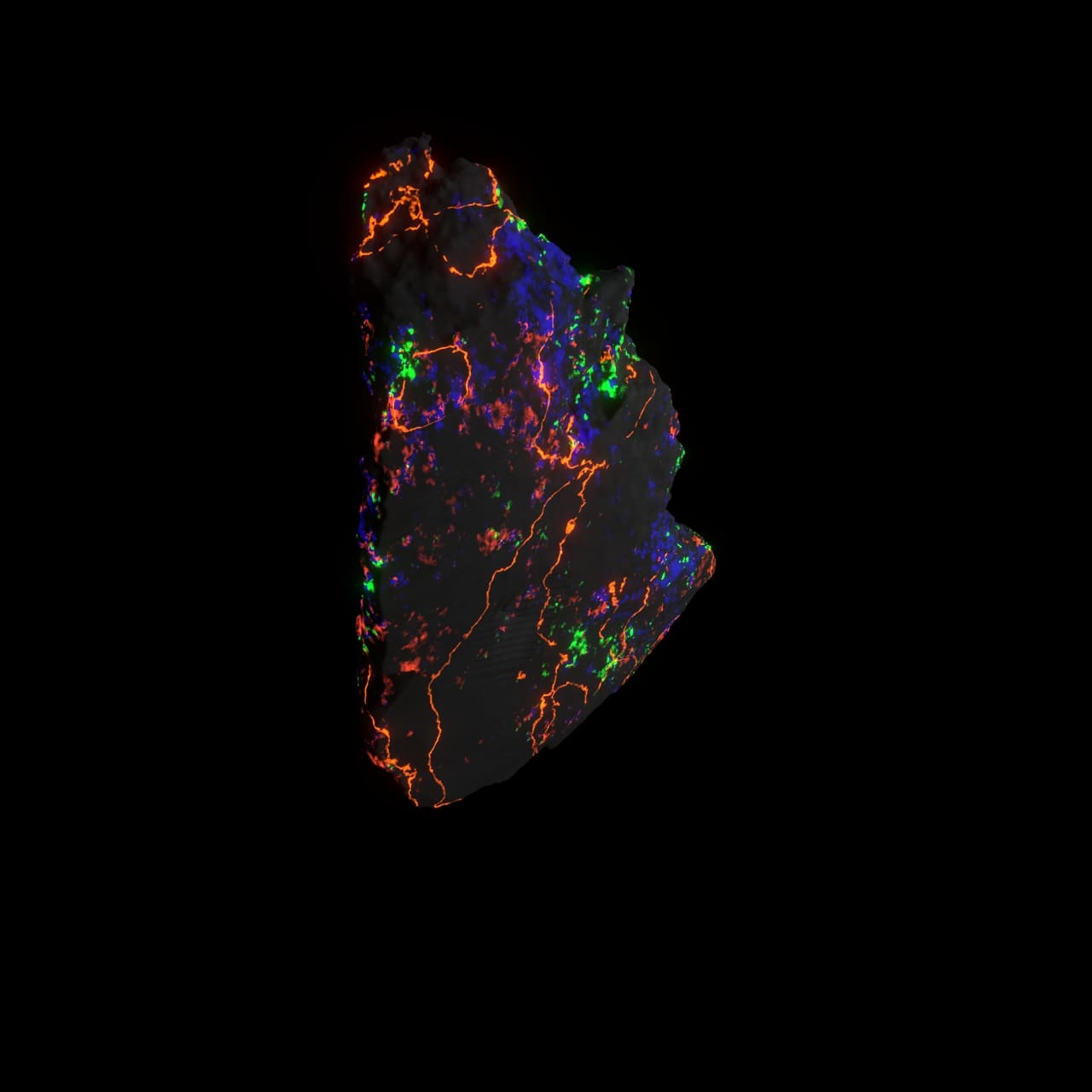

The selection we made aims to reflect the diversity of artistic cultures that is the hallmark of the web3 landscape, crossing the fields of digital art, crypto art and contemporary art that addresses the particularities of the decentralized economy. From as early as 2015, Sarah Meyohas’ conceptual project Bitchcoin delivers a persiflage of the value system constructed by the blockchain, where the glamour of branding, financial speculation and symbolic capital are intertwined. We felt it was essential to include pioneering crypto artists such as Robness and Larva Labs, who were among the first to explore the artistic possibilities of blockchain, with a countercultural and DIY spirit. Fusing Pop and generative art, the CryptoPunks have become unwilling icons. John Gerrard places environmental issues at the heart of his work, highlighting the inextricable link between technological advances and the alteration of natural resources. He is an artist who exploits the principle of the metaverse to its fullest, the NFT being for him bridge between the physical world and the virtual world existing in parallel, in real time.

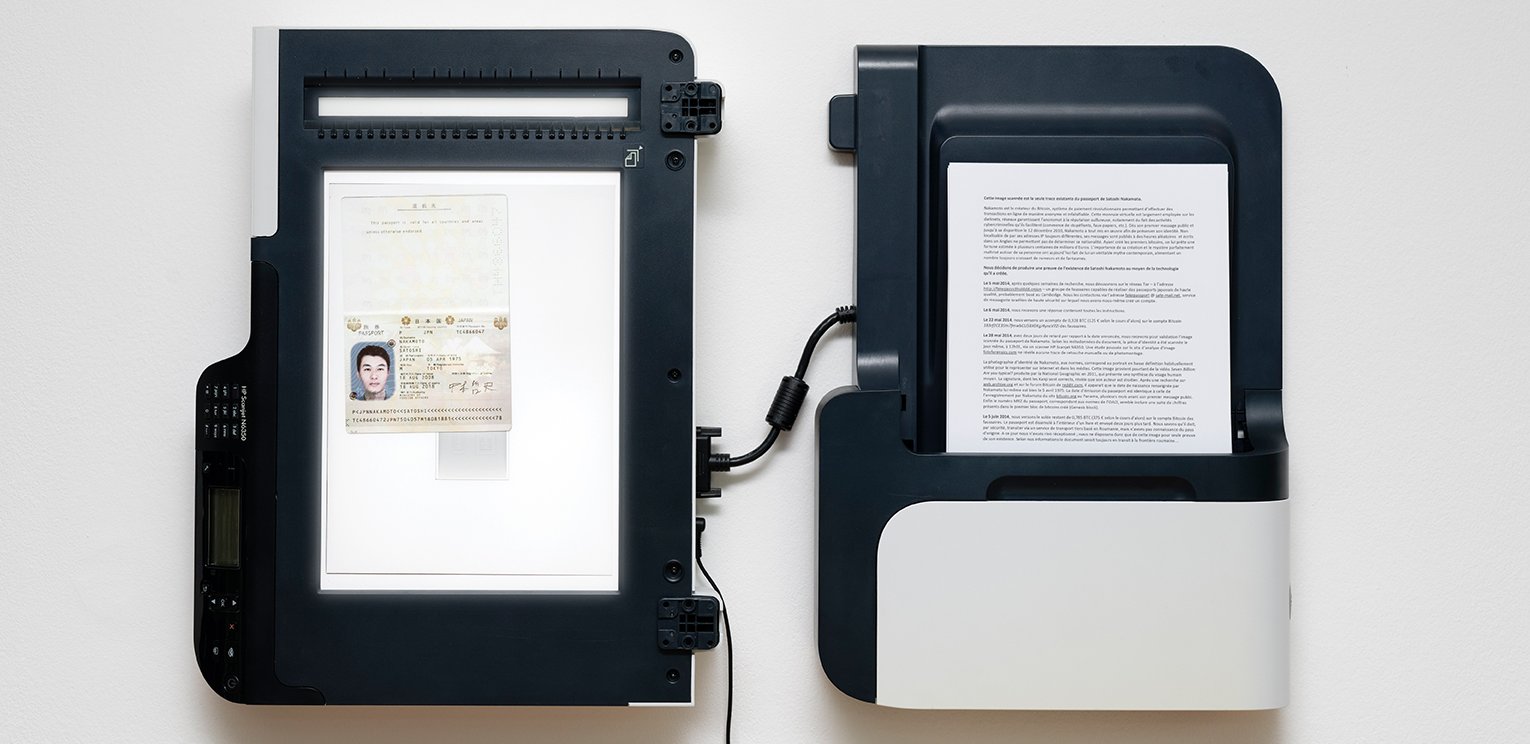

We’ve also acquired two works that are not NFTs, but that have a strong link to the rise of web3 in art. One of these is an attempt by Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion to provide evidence of the existence of the inventor of bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, through the purchase of a fake passport in his name on the dark web. The other is a critical piece by Claude Closky, consisting of a fake sales platform on which every NFT is already sold. It was important for us to show that NFTs have been met with debate within the field of digital art, and that some artists strongly felt that this phenomenon was not a positive development in the ecosystem they wanted for online art.

A key question for us has been the status of the token itself: why did the artist choose to work with NFTs? Is the token a conceptual part of the work, or is it only a record of the transaction, as traditional sale certificates would be? We have also had practical questions to consider. There’s the issue of wallet security, which requires specialized technical knowledge. We have had to think about the preservation of on-chain information, and acquire display devices such as square screens, widely used for the presentation of NFT works.

Nevertheless, the core approach to conservation remains the same: technological migration of the works through the various stages of their technological obsolescence, precise documentation of the works in their original environment, discussions with the artists regarding what constitutes the work, its possible displays and the extent to which it can evolve through the stages of its preservation. Of course, time only will tell if more specific issues should arise, which may make us reconsider our approach.

Last month we opened the first museum presentation of the eighteen digital works we acquired. We have also included a selection of pieces and documents that show the history of the dematerialization of the work of art through specific transaction devices, such as certificates, protocols, and vouchers of all kinds. Among these is the famous Chéquier conceived by Yves Klein in 1959 for the transfer of a “volume of immaterial pictorial sensitivity.” The questions being broached by artists through NFTs should be understood as in dialogue with the work of earlier generations of artists.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz.