Fabric Media Collection

An anonymous collector in St. Louis talks about their mission of proving that NFTs are a viable equity strategy.

Kensuke Sembo and Yae Akaiwa, who collaborate as the duo Exonemo, have been exploring the relationship between the physical and digital for two decades. In 2004 they painted Google’s search page on a wall-size canvas, then trained a webcam on it to put it back online. Their works often touch on the emotional parameters of digital media, and they were drawn to NFTs by the promise of collectability and how that impacts the personal connections people have to digital objects. “Metaverse Petshop,” Exonemo’s recent exhibition at NowHere in downtown New York, featured animated 3D models of dogs that could be converted to NFTs as a way to examine the overlapping associations between ownership and companionship, living things and works of art. Below they discuss that project and others involving the sale of immaterial items.

Our work combines the analog and the digital. We started the Internet Yami-Ichi in Tokyo in 2012. That was the time of the post-internet movement, when some artists were converting digital pieces and bringing them into the physical world. We were inspired by Comiket, a traditional Japanese comic market, where people sell all kinds of random things, not just comics. So we reimagined that idea in light of the internet, to make a place where artists could sell zines, toys, posters, digital files—anything. We’ve held it in many places around the world.

At our own Yami-Ichi table we sold a spacer gif, a file that was used to create negative space on websites in the early days of the internet. We used some tape to make different shapes on the table, to express the size that the gif could come in. Some of them were very big. We’d pretend to hold the gif in front of people, pantomiming. If people asked for a really big one, we’d pretend to haul it from the back and pass it to them. But it was just air. It was a kind of performance. Earlier this year we put out a book called A Decade to Download that collects the history of the Yami-Ichi. Making a book is a bit like minting an NFT. Once it’s published, you can’t change it, the same way that when you deploy a contract to the blockchain you can’t change it.

We joined Foundation last year to see how NFT sales work. Some of our existing collectors have used the platform to buy our NFTs. We’ve also encountered a new type of collector—younger people, crypto natives. We don’t have a big audience in that area yet. We don’t have a collector mentality ourselves. Our wallet just has some utility NFTs and NFTs that we minted of our pieces that are still in our wallet. But the wallet was the inspiration for Connect the Random Dots (2021), a book with dots in random positions.

If you connect the numbers, an abstract drawing appears. The biggest one has 80,000 dots. It takes about ten hours to connect them. First we printed the book. Then we minted the pages as NFTs and sold them at the Tokyo gallery Waitingroom, where we also showed the pages on the wall as drawings. Collectors could buy the NFT and the page drawing together. Our concept was that NFTs are like connecting dots—the wallet and the NFT are connected to each other. If you send an NFT to someone, then all the lines are coded on the blockchain. So we want to connect the lines of the physical book to the blockchain, too. The book has thirty pages and we kept the first two.

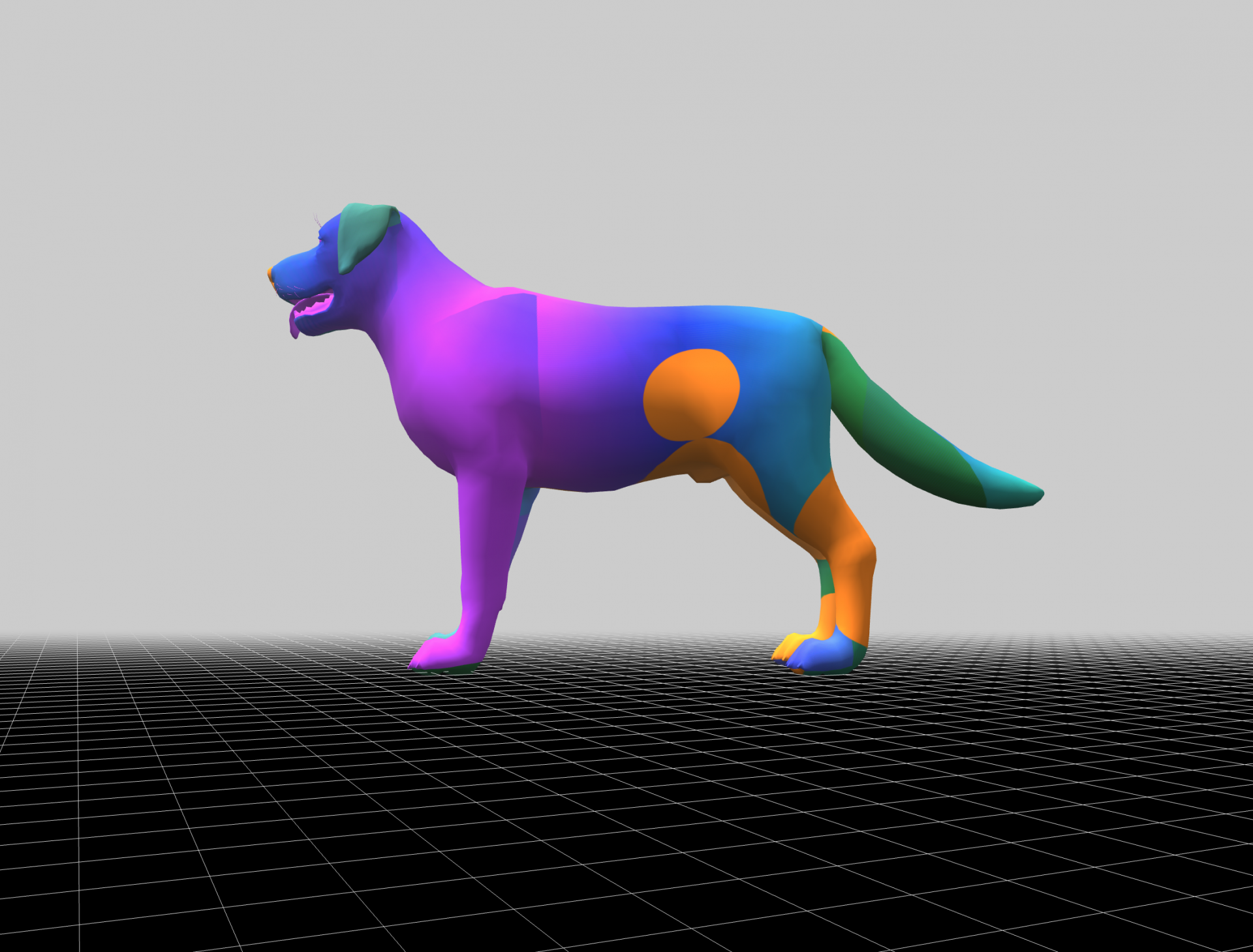

Metaverse Petshop,our most recent project, is a little twisted. We showed 3D models of dogs on screens in cages, like in a pet shop. People could buy ownership of a digital dog, but it’s not an NFT. The owner could convert the dog to an NFT, but that would mean giving up the model. It’s like skinning the dog, taking the texture from the dog to make a 2D image, which can be converted to an NFT. We think of it like making leather from an animal: you kill the animal, then peel its skin and flatten it, so the product lives longer than the animal did. An NFT has a longer life than usual data.

We converted some dog NFTs for this exhibition, so we own about ten. A few other people choose to do that too, but most just keep the dog. Owning pets and owning art are totally different experiences. Owning a pet is more like having a new family. There’s more responsibility. But when I sell our artwork to a collector, it’s like selling a pet because they need to maintain our work, like a pet.

If you collect a painting, then you only hold it in your room. You can hide it from the public. But with NFTs, all the data is basically public. The amount paid for the work is public. That’s very interesting. NFT collectors want everyone to know how much they paid to own something, even though everyone else can see and download the data they own. This attitude is very different from the traditional art world. In some ways it’s similar to spending millions of dollars on a van Gogh, but it’s more conceptual with the NFT. It’s very surprising for us how many people have gone along with that idea.

Selling editions for digital art in the past was a bit strange. It just relied on trust between people. Digital data can be copied, that’s a basic feature of the digital object. So imposing that limitation somehow doesn’t make sense. With NFTs, the scarcity of the data is recorded on a very robust database called blockchain—and because of that everything changes. We can track the transactions and how much was paid. It’s all transparent. Maybe it’s strongly connected with human greed, with the desire to be special, or a desire to be close to power. We’re interested in observing people do that.

—As told to Brian Droitcour