Painting the Blockchain into History

Robert Alice endows Bitcoin with the gravitas of inevitability by enmeshing paintings of its founding code in a network of references to histories of art and computing.

A screen can seem haunted: the black mirror flickers alive to host images and voices from afar. It’s fertile ground for horror movies. At the beginning of The Ring (2002), a pair of teenage girls talk about the electromagnetic signals passing invisibly through the air and through bodies—aren’t they harmful? One of them dies after watching a mysterious videotape, and her aunt undertakes an investigation to figure out how images on a screen can kill. An attempt to identify the tape’s origin by analyzing the tracking data doesn’t work—the display flashes illegible glyphs instead of the numbers that should have been there. Technology fails, and the source of the tape’s deadly power is traced instead to a ghost story about psychic abilities and family trauma.

Plots like The Ring’s play on the anxiety around the dark squares we live with. A lack of knowledge about their technical workings leaves room for fear. In so much contemporary horror, on-screen monsters personify the complex, confusing networks of commerce and communication that make suburban comforts possible; they’re chickens coming home to roost. There’s nothing overtly spooky in “I’ll be Your Mirror: Digital Art and the Screen,” an exhibition curated by Alison Hearst at the Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth on view through April 30. Yet the show trades in the mysteries surrounding this ubiquitous technology. The Modern is no science museum, so there’s no explanation of how screens works, or historical specificities like the shift from CRT to LED monitors, or the differences between projection screens and monitors—though various types of display are represented in the nearly seventy works spanning four decades. Instead, the journey Hearst takes us on is a bit like the protagonist’s in The Ring: it locates the essence of the screen in psychological and sociological narratives. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” follows the supply chain that put screens in our hands and our homes, with works addressing the extraction of resources needed to manufacture consumer tech, the international trade networks that get these devices in our hands, the cultural exchanges they enable, and the visual tropes and memes propagated by the internet.

The singing faces might as well be electrons hitting the glassy surface from behind to create an image stream.

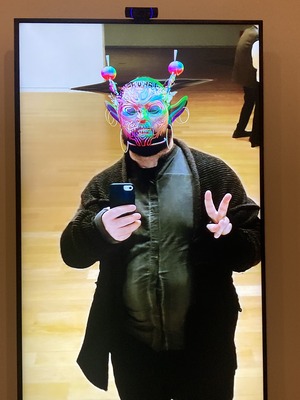

In Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha (1992), positioned at the show’s entrance, a religious idol sits before a monitor hooked up to a closed-circuit camera. The screen displays a serenely static image, a mirror-like reflection of the Buddha before it, but also captures any ambient movement in the camera’s path. This fixed loop neatly demonstrates one way an image can appear on a screen, but despite the simplicity there’s still something uncanny about it. Here is one image of the Buddha, a figure that exists in limitless iterations, including images taken by a camera like the one in the installation. The statue is itself an image modeling the act of focused contemplation, but your own gaze as the viewer is fragmented—your attention goes to the Buddha statue, to the Buddha’s image, and to the equipment that splits them. A pair of recent works in another gallery turn the mirror on you. Huntrezz Janos’s augmented reality filters Hologram Mythography and Tinsel Polycarbonate (both 2019) project demonic, quasi-ceremonial masks onto the viewer’s face, reshaping the audience in an image fashioned by the artist. Janos, like Paik, teases out the screen’s status as a site of highly personal yet highly standardized experiences.

Molly Soda’s video Me Singing Stay by Rihanna (2018) collages forty-two renditions of the titular pop song found on YouTube into an orderly grid. The voices overlap, not singing quite in the same rhythm or meter, striving to emulate something they admire in the hope that the singers will receive admiration themselves. The sound becomes dissonant, and the search for recognition of individual talent through imitation gets fuzzy, too. The “me” of Soda’s title aligns with the “I” in the title of the exhibition, which personifies the screen; the singing faces might as well be electrons hitting the glassy surface from behind to create an image stream. Their expression of feeling ends up depersonalizing them. Petra Cortright’s VVEBCAM (2007) alludes to the same condition, but she appears before the webcam herself. Her demeanor is cool and detached; she doesn’t look at the camera, but instead at her own screen, manipulating the animations offered by the webcam’s software for decorating the stream. The persona she presents here is less interested in self-expression than ticking through the default tools offered to that end. The 3D printed sculptures from Morehshin Allahyari’s series “Material Speculations: ISIS” (2015–17) present another dynamic of movement through the screen. Allahyari collaborated with historians to create digital models of ancient artifacts destroyed by ISIS. Ancient objects were translated into points in virtual space to be resurrected as physical things; like TV Buddha, Allahyari’s sculptures reflect on the identity of the object as mediated by the screen.

The screen as presented here is singular and plural, eternal and ephemeral.

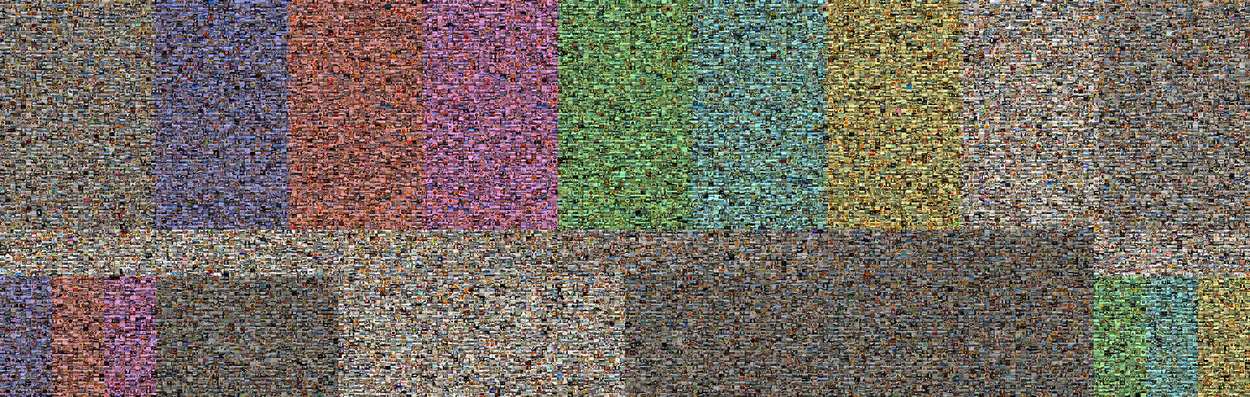

Hasan Elahi was targeted by the FBI after 9/11 because of his name and travel schedule. Thousand Little Brothers, v8 (2022) collects more than 30,000 images of meals and places that he took and sent to the FBI to protest the absurdity of the investigation. They are organized in a print that covers three walls of a gallery, grouped in tinted rectangles that evoke a TV test pattern. This nostalgic allusion exaggerates the prophetic nature of the project; Elahi’s project prefigured the voluntary self-surveillance conducted on social media a decade later. Kahlil Robert Irving also presents a digital diary as printed wallpaper, Hidden MASS &: Screens (threw views and artifacts) (2023), but this one captures his online life, rather than daily presence—a reflection, perhaps, on how much of everyday life now takes place in the frame of the screen. The artist’s internet history from 2020 onward includes Zoom calls, doomscrolls, exhibition plans, fraught updates on Covid and protests. Like Elahi’s installation, Irving’s fills a gallery. In these works, that which was contained by the screen spills beyond its borders, tracking its variation over time.

While most works are about what happens on and with screens, some consider their material history. Works from Simon Denny’s “NFT Mine Offset” series (2021) consider the extraction of mineral resources needed to fuel networked activity, while Elias Sime’s Tightrope: Contrast (2017) is a monumental relief woven from the wires salvaged from e-waste and sold secondhand in the markets of Addis Ababa. The work highlights the circularity of how minerals are mined in Africa to produce goods that return there as scrap. Cao Fei’s Asia One (2018) is a surreal film set in a sorting warehouse, where screens are not only stored and shipped, but also used as management tools.

“I’ll Be Your Mirror” could be seen as a late entry to the wave of surveys about art and the internet that passed through museums in the 2010s, such as “Electronic Superhighway (2016–1966)” at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and “Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today” at the ICA Boston. But its object of inquiry makes it quite different. Those exhibitions declared their subject to be the internet—something invisible, hidden, amorphous. The results replicated the internet’s effects of proliferating connections, incongruencies, and tangents, offering semantic overload rather than a coherent narrative throughline. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” has some of that looseness, as will any survey that aspires to be historical and global in scope. Yet the focus on the screen gives it a material referent, a concrete image that returns in many iterations. Like Nam June Paik’s Buddha, the screen as presented here is singular and plural, eternal and ephemeral. Like the exhibition itself, the screen is a conduit for other ideas, tendencies and trends, collecting them, momentarily, and letting them slip back out into the world.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.