Weird Blob

A collection of NFTs inhabited by a mysterious, shapeshifting sea creature raises existential questions about the simulation of autonomous life forms.

On June 30, the US Supreme Court determined that the Environmental Protection Agency had exceeded its authority with the Clean Power Plan and could not impose limits on greenhouse gas emissions. This is the kind of indifference to the realities of the global climate crisis that fuels the work of Ireland-born, Austria-based artist John Gerrard, who seeks to raise awareness about the operations of the global energy enterprises that sustain—and endanger—our way of life. Gerrard is one of the few artists with a serious history of exhibitions in galleries and museums who embraced NFTs early on; for him, it was an extension of his longstanding engagement with 3D modeling, simulation, and other digital technologies. Petro National (2022), his third NFT project, emphasizes inconsistencies in the discourse about climate change in the mainstream media and the art world, as both spheres lambast NFTs released on proof-of-work blockchains for their carbon emissions.

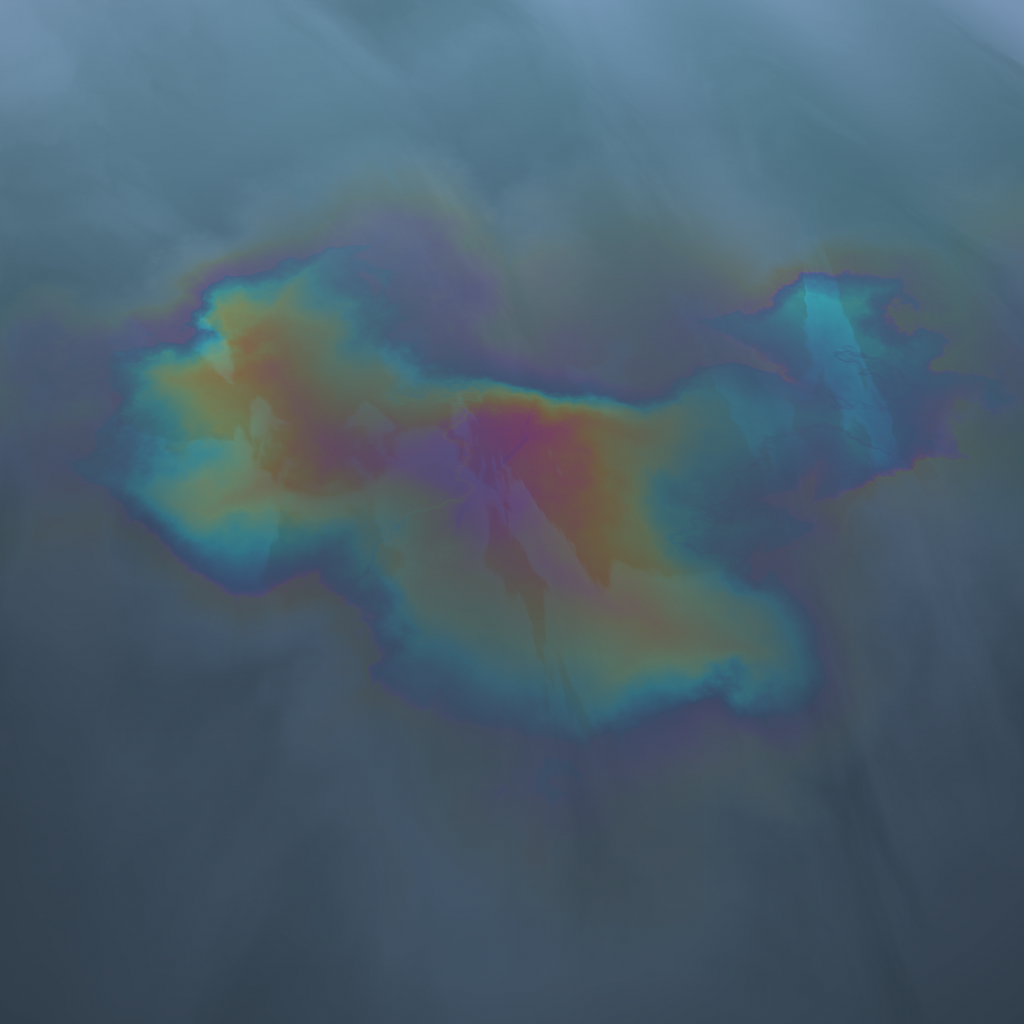

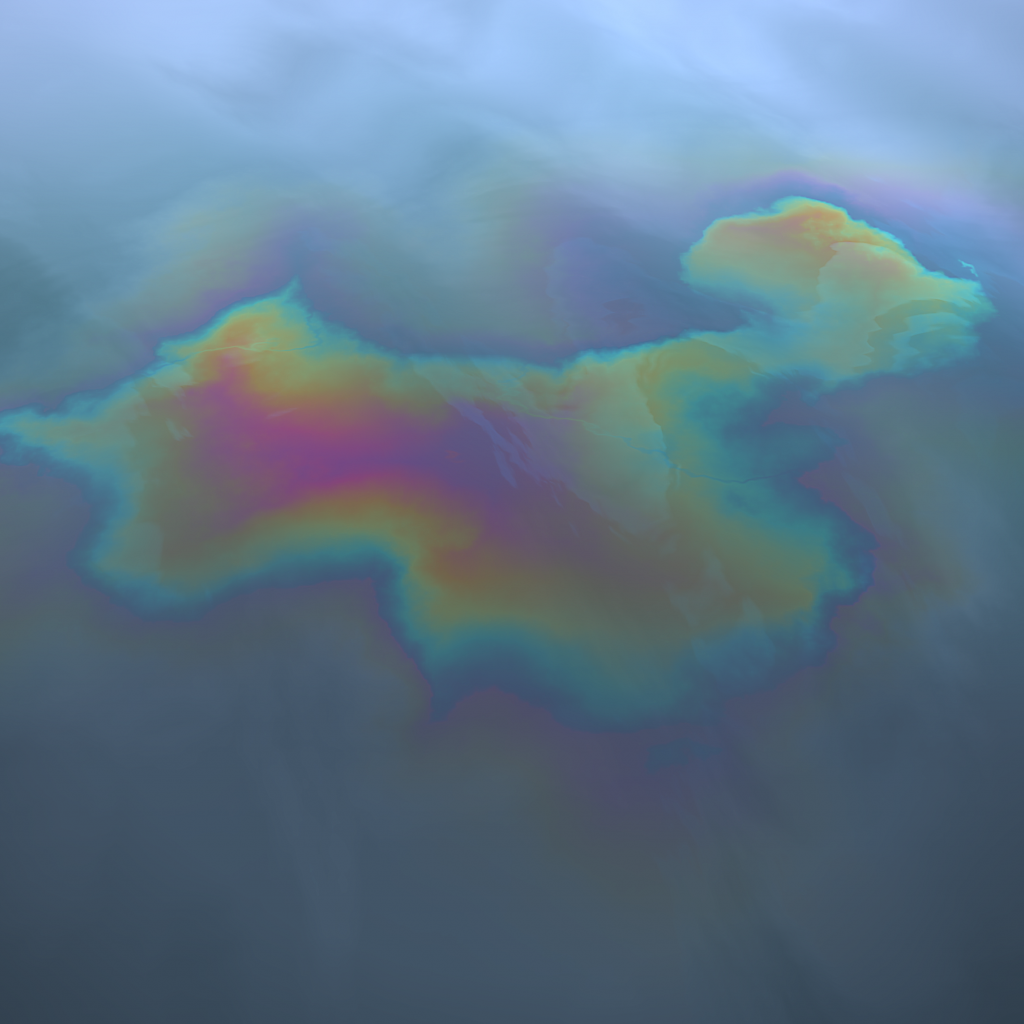

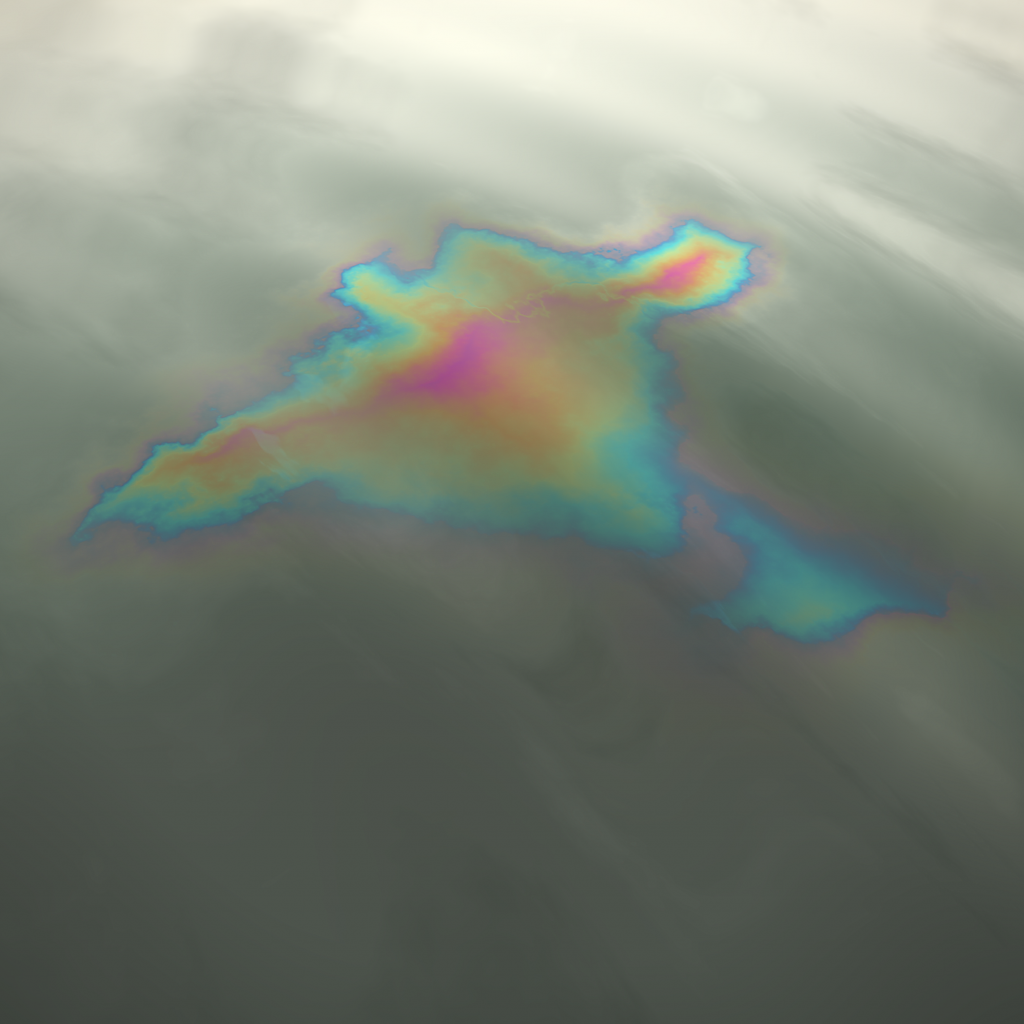

Petro National is a set of 196 simulations of iridescent oil slicks floating on the surface of water. They represent the 193 members of the United Nations, plus Taiwan, Palestine, and the Vatican, with the shape of each slick roughly corresponding to that of the country it stands for. Gerrard researched per capita gasoline usage for each nation, and those figures determine the density and variety of color in each simulation. Slicks representing countries with less usage are a light muted green (as in #175, based on data from Uganda), whereas greater consumption translates to a glossy rainbow (as in #8, the United States). The viscous sheen glistens, epitomizing the shiny and colorful consumer lifestyle enabled by extractive capitalism. Its beauty is disconcerting. Other data points also influence the appearance of the works. Each one is programmed with the time zone of the capital city of its assigned nation, and the quality of light in the simulation changes by the hour. The works are spatialized, so that dragging a computer mouse shifts the perspective—a reminder of the importance of our positions to what we see.

The viscous sheen glistens, epitomizing the colorful consumer lifestyle enabled by extractive capitalism.

This awareness of space stems no doubt from Gerrard’s sculptural studies at the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford, England, where he also became interested in digital media. After receiving an MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2000, he pursued a graduate degree in computer science to learn more about the technologies he wanted to use. Three residencies at Ars Electronica from 2002 to 2004 introduced him to the community and colleagues who influence and support his use of game engines and simulation software to model natural environments and the impact of human activity on them. Programmer Helmut Bressler and producer Werner Poetzelberger are longstanding collaborators who ensure the high level of craft evident in Gerrard’s work.

Last year, Gerrard produced Western Flag (NFT), on Foundation. The work was based on his 2017 simulation Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas), which presented a billowing rectangle of smoke atop a pole, mimicking a flare from an oil refinery. Later in 2021, he released another adaptation of a pre-existing simulation, Crystalline Work (Arctic), on the Binance NFT marketplace, this time addressing the absurd proposals people have made to manage the melting of the polar ice caps. These new works extended his aesthetic and conceptual projects into the realm of NFTs, although the gridded interfaces of the marketplaces he was now using immersed his simulations in a morass of aesthetically dissimilar projects. But Gerrard was still interested in this new technology for art, so he continued seeking a way to bridge the worlds of art and NFTs.

Petro National launches a new partnership between the megagallery Pace and the popular generative art marketplace Art Blocks. It also reinforces Gerrard’s commitment to NFTs. He is assuming a responsibility to guide his Pace collectors through the practicalities and the concerns of the blockchain landscape, while taking on the challenge of engaging the Art Blocks audience in the discourse of contemporary art. In the case of Petro National, this means participating in an uncomfortable conversation about carbon footprints—both of the traditional art market and of the NFT market. The advent of NFTs, most of which use Ethereum (for now, at least, an energy-intensive proof-of-work chain), has deferred criticism of the art market’s dependency on fairs and the ecological costs of related shipping and flights.

Attending Art Basel’s vernissage this past June meant walking by the booth of Tezos, a proof-of-stake chain popular with artists because of its lower carbon impact. The booth’s prominent position seemed to encourage attendees to talk about NFTs. I was consistently asked about their environmental impact, even while standing in Unlimited, a section dedicated to large-scale installation works freighted across land and ocean. The incongruity was startling. But although Art Basel paid for offsets of their staff, VIPs, speakers, and press for its 2019 edition in Miami Beach, there was no mention of such initiatives this year. In contrast, many artists in the NFT space commit percentages of their sales to carbon offsetting and various environmental causes, even if using proof-of-stake chains that are far less energy consumptive. Art Blocks offsets carbon emissions beyond the original minting; as of writing, this totals over 20,000 tons, which is equivalent to more than 1.5 million transactions on Ethereum.

Artists selling NFTs are forced to acknowledge the ethics of their use of technology.

Carbon offsets reduce or remove carbon emissions in one area to compensate for the production of carbon in another. Claims of carbon market manipulation and duplicitous “greenwashing” practices have generated doubts about the usefulness of offsets; now there are concerns about disequities in carbon markets. Gerrard prefers to support carbon sequestration practices, reversal efforts that remove petrochemicals and nitrogen fertilizer from soil or air; for example, carbon drawdown captures carbon dioxide in the air and locks it in plants, soils, rocks, depleted oil wells, or long-lived products like cement, for decades or potentially centuries. A quarter of the artist’s proceeds from Petro National will support atmospheric carbon removal, with additional funds contributing to regenerative farming organizations. Meanwhile, though Gerrard’s projects to date have used Ethereum, he is not a maximalist and is looking forward, he said in a recent interview, to a forthcoming project on Feral File using Tezos.

In his art and his distribution of revenue, Gerrard exemplifies how artists selling NFTs are forced to acknowledge the ethics of their use of technology. It’s unfortunate that conversations on this topic have dissipated elsewhere in the art world. We are all culpable for damage done to the planet. There is no obviating the harm we do. Recognizing our shared responsibility allows us to seek out all the places in our lives where we can do better, and know that this will always be a process of improvement.

Charlotte Kent is an assistant professor of visual culture at Montclair State University and an editor-at-large at the Brooklyn Rail.