NFTs in the Ivory Tower

A conference at Oxford brought together experts from art, business, and technology, attempting to define the field of NFTs in broad strokes.

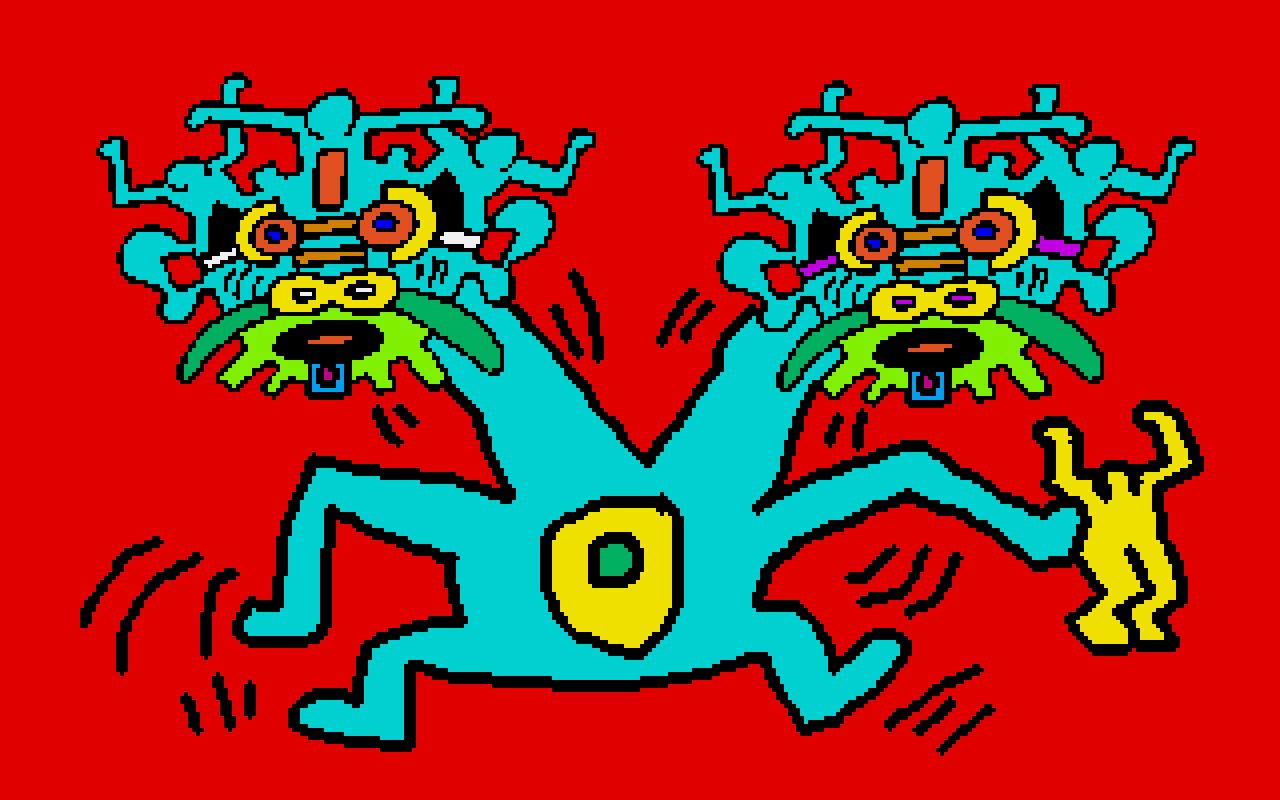

Keith Haring was promiscuous with mediums and surfaces, painting walls and floors as eagerly as canvases, wheatpasting xeroxed collages, selling T-shirts and posters, documenting his life and art with polaroids and video. So it’s not surprising that he jumped at the chance to draw with a computer. Timothy Leary, the psychedelics guru, got obsessed with virtual reality and cybernetics in the 1980s. His software company was developing a game based on William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer; he asked Haring, whom he’d met through Grace Jones at Paradise Garage, to make some art for it. He gave Haring a Commodore Amiga computer to play with, telling him “This is the hot graphics computer that Andy [Warhol] helped publicize last year.” Haring sent Leary back a floppy disk with five drawings on it. They were found by researchers in Leary’s archive in 2013; a digital archivist detailed their history in a post to the New York Public Library’s blog. Now they have been restored and put on the blockchain through a collaboration between Artestar, a licensing agency that works with the Keith Haring Studio, and web3 development studio Digital Practice, to be sold in an online auction by Christie’s starting next week. The initiative offers a new approach to using NFTs not only as certificates of authenticity, but also as storage mechanisms that offer multiple options for preserving and displaying historical works of digital art.

The Haring NFTs might be seen as a response to the controversy around a 2021 Christie’s sale of five digital Warhol drawings.

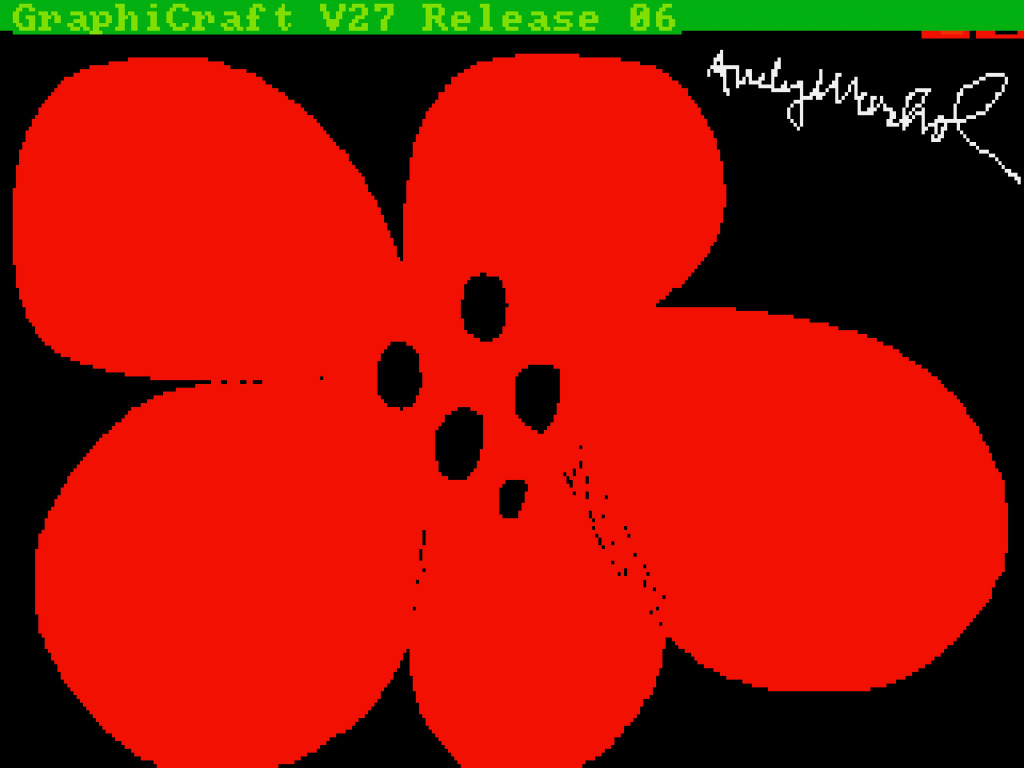

The Haring NFTs might be seen as a response to the controversy around a 2021 Christie’s sale of five digital Warhol drawings, which were made around the time of the event that Leary referred to in his note to Haring. Warhol used an Amiga to produce a portrait of Blondie singer Debbie Harry at a press conference at New York’s Lincoln Center in 1985. The artist Cory Arcangel, as he wrote in a 2014 essay for Artforum, surmised that Warhol’s performative facility with the computer meant that he must have made other drawings with it, so he approached the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh to investigate the disks kept in its archive. Warhol didn’t save his drawings neatly to a dedicated floppy like Haring did—he kept them on various boot disks and systems disks. But file names like cambell.pct helped identify them. Students and professors in the computing club at Carnegie Mellon University worked to get the files off the disks, and the museum presented them in the exhibition “Warhol and the Amiga,” on view from 2017 to 2019. Warhol’s own computer was included in the show as one means of displaying the recovered files.

The 2021 Christie’s auction, which raised funds to benefit the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, sold versions of Warhol’s Amiga drawings as high-resolution tiff files, linked to NFTs that serve as certificates of authenticity. The restoration team back in Pittsburgh was not consulted, and they weren’t happy with the language around the sale. Golan Levin, a media artist and professor at Carnegie Mellon, posted Twitter threads lambasting Christie’s for claiming to offer collectors the original work, when they were in fact selling a high-resolution file with dimensions of 6000 x 4500 pixels, significantly upscaled from the 320 x 200 pixel version that Warhol created. A collector today might prefer to display a digital Warhol on a big contemporary screen rather than a device approximating the original hardware—and that potential preference was prioritized over fidelity to the Amiga’s specs. The Warhol Foundation rejected Levin’s criticism, asserting its prerogative to authenticate a Warhol. The controversy didn’t seem to affect the success of the auction; the five lots netted 3.4 million USD. (One was acquired by Jehan Chu, who in an interview with Outland about his NFT collection said: “Some people think the original pixels […] are what make something art. I think that’s silly. Retouching and conservation are normal aspects of maintaining works.”) A year after the Christie’s sale, Bonham’s auctioned a disk from the collection of a Commodore executive containing nine drawings by Warhol—some of which are nearly identical to the ones in the Christie’s sale—along with an Amiga computer to display them on. The lot sold for 252,375 USD. There were no NFTs involved.

The Haring sale suggests that Christie’s learned some lessons from its 2021 Warhol auction. The solution developed by Digital Practice and Artestar offers both flexibility and fidelity, encompassing files suitable for display on today’s screens as well as a faithful replica of the original pixels in contemporary code. Digital Practice has coded NFTs for a number of platforms operating in the art world, including Outland, and applied that experience to working with the Haring files. A technical document shared by James Healy, founder of Digital Practice, describes the process of studying the binary code from Haring’s files to identify the colors used by Haring and preserving that data in multiple formats. One version of the artwork in each NFT is a translation of the obsolete file format’s ones and zeroes into Solidity, the programming language used to write smart contracts on Ethereum, so that the original bits can be recalled from the blockchain for historically accurate display. A second version adapts Haring’s image as a png file, an image standard that supports the color tables used by the original and that can be rendered on any contemporary computer. A third version embeds the png in an svg, a scalable format that keeps the image crisp when enlarged, so the works can be displayed at variable dimensions. The NFTs store all three files as text on the blockchain rather than pointing to files kept elsewhere, eliminating the risk of broken links associated even with decentralized servers.

Haring’s body of work poses some quandaries for preservation. As previously mentioned, it spans collectibles and ephemera like clothing and club flyers as well as monumental paintings, like the 85-foot mural extracted from a former youth center on the Upper West Side and sold at auction in 2019. In other words, Haring’s art requires a variety of approaches to preservation because it is both very big and very small. So it’s appropriate that the solution for preserving his digital art allows for scalability. And it’s a good thing that they have been preserved. Judging by the restored drawings, the Amiga was a suitable vehicle for Haring’s bold, happy line. He favored figures without facial features, whose moods are conveyed by the curvy lines around their bodies that express states from agitation to joy. The thick contours of his figures and the solid fields of color that fill them work nicely within the limitations of early drawing software. Only the last drawing Haring made on the Amiga—dated April 16, 1987, about two months after the first—attempted a modulation of color, simulating three dimensions with mottled pixels crossing a gradient from brown to green. The suggestion of volume on a screen within a screen is a departure from Haring’s signature style that plays with the textures specific to digital media—a fascinating suggestion of another direction his work could have taken had he continued using the computer.

The Haring NFTs demonstrate that the smart contract can be a flexible tool, accommodating the various needs and contexts of digital art.

It doesn’t seem controversial that these Amiga drawings are significant exponents of Haring’s art. So the more interesting aspect of this release is the argument for NFTs implicitly made by the restoration process. Too often NFTs are written off as tradable assets, as “expensive jpgs.” The Haring NFTs demonstrate that the smart contract can be a flexible tool, using metadata and code to accommodate the various needs and contexts of digital art. No digital image exists in a fixed state. The preservation and display of digital art rely on a complex ecosystem of software and hardware. This is as true for art made today as it is for art made forty years ago. The Haring NFTs propose a standard that takes this into account.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.