Dina Chang

The creative producer discusses some highlights from her personal NFT collection.

Tim Whidden is a web developer and new media artist. He’s currently vice president of engineering at luxury online marketplace 1stDibs, where he leads the platform’s exhibition-based NFT sales channel. From 1996 to 2011, Whidden was also a member of influential net art duo MTAA alongside Michael Sarff. Together, the pair created a body of work that investigated networked culture with humor and a critical eye, including the much-adapted Simple Net Art Diagram (1997). Whidden now owns that work as an NFT, and it fits well in his collection, which includes several works by canonical net artists who are adapting to this new space. Below he discusses his collection, his evolving experiences as an artist working online since web 1.0, and the new, exciting opportunities he sees for artists today.

People working with net art back in the late nineties and early aughts put words and thoughts into our heads about what we were trying to do in terms of selling and collecting art online. There was a contingent, mostly based in Europe, who were decidedly against the market or anti-gallery, but not everyone was thinking that. MTAA definitely wasn’t thinking that. We wanted to sell work but it was really hard—there weren’t any good mechanisms to sell digital art, particularly if it was on the internet.

We made a lot of complex work that needed to be running on a server or in software in the browser. We made static files, whether it was a jpeg, or a gif, or a video—but we wanted that to be on the internet, too. We wanted it to live there. We wanted everyone to see it, but there was no way to sell that type of thing at all until NFTs came around. I even tweeted in 2014 asking if there was anyone working to sell art on the blockchain, because it seemed like an obvious thing someone must have been working on at the time. Later in the year Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash released Monegraph at Rhizome’s Seven on Seven.

But, I didn’t really get serious about NFTs until early 2020, when I started advocating for them internally at 1stDibs. In mid-2020 I started learning the technology because my role at 1stDibs is to implement the actual tech that we need to run the company, and by the end of the year the volume flowing through the NFT ecosystem allowed me to get the go-ahead to go full force. We put together a team in March 2021, and shipped our first iteration of an NFT marketplace in August.

While I was doing that, I wasn’t collecting a lot of NFTs. If you didn’t have that good crypto dough from back in the day, it was hard to jump in at that point. Probably the first thing I purchased was my ENS domain (thanks to Billy Rennekamp for giving me a push). That’s technically an NFT. That proved important later because I traded my ENS tokens for Ethereum, and then did a little bit of collecting with that. My first purchase was Chameleon #19 by Joan Heemskerk. I know JODI from way back in the day and I thought it was really special to own one of their pieces.

My collection has more old-school net art folks who are coming across to the NFT world. I know a lot of them personally. But Jimpunk (aka l__lll__l_l_ ), I don’t know who they are—Rick Silva, who collaborated with them on Screenfull from 2004–2005. doesn’t even know who they are. But when they started listing work on Hic et Nunc I wanted to support them. Punk 009 is great because it was an edition, but I was the only one to buy one. Then Jimpunk burned the rest.

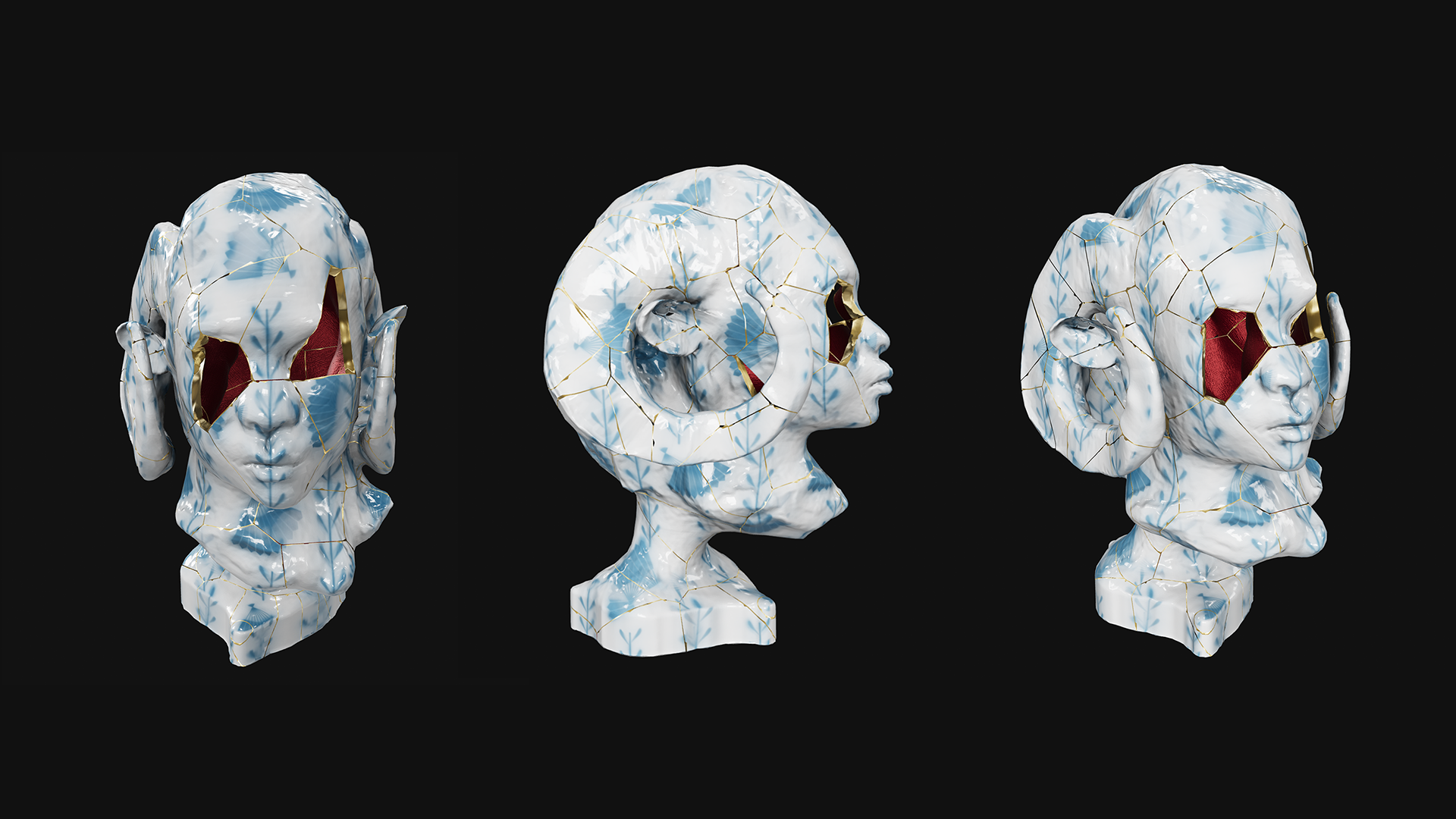

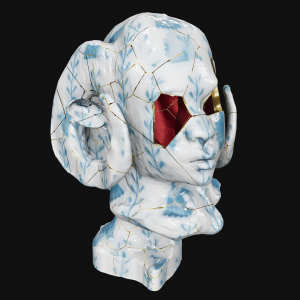

RAM v2-dv1 by Auriea Harvey is cool. Its beautiful. It looks like it has this history, this mythology, with an animal quality. It feels special, somewhat luxurious, but then it’s broken. If you had a house, you’d want to put something like this on a pedestal somewhere and have it around you. My only strategy of collecting so far is getting work from artists who I admire quite a bit, and Auriea is one of them. She’s a legend, and the fact that I could get a piece of hers for a relatively small amount of money in relation to her other work meant a lot to me. I could then identify myself with her work, and share it with others online, which is something I haven’t really done before with work I’ve purchased. I own art that I hang in my house, whether it’s my own art or other work I’ve acquired, but being able to have Auriea’s work and share it online so that anyone can come and see it is really nice.

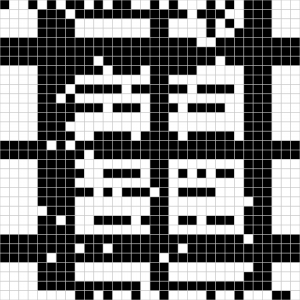

The only historical internet art piece that I own that was completely redone—and I think they did a really good job with it—is Every Icon.

Fingerprints DAO, Divergence, and e.a.t.}works took John F. Simon, Jr.’s original code that was written in Java and they ported it over to the blockchain. So the state of the icon, as well how it gets drawn, is all on-chain. And it generates an svg file that is animated in the browser. With a lot of on-chain generative projects, you don’t see what you get until you mint the token. Every Icon had this cool feature where you got to click through options—there were 800,000 different variations—when you found one you liked you could pick it, which was pretty fun. It was also stressful, because you only had one choice and couldn’t go back to options you’d already skipped through.

I use Showtime to display my NFT collection. I’m sure there are—and will be—more ways to do this. Twitter is going to adopt it most likely, too. It’ll happen more and more that your identity online can be associated with your collection. I think the exhibition aspect will be big for people who are in it for the art—people who are in it to flip it, not so much. I think that the gulf between those two types of collectors is becoming wider as time goes on. What I’m seeing and interacting with, the flippers and the 10K PFP projects aren’t getting. Those projects have some art in it— just like a comic book has some art in it—but it’s not necessarily art that you would think of as stand-alone.

Then you get into this weird area where the two methods of collecting are mixed up. Joan’s Chameleon had 256 pieces that collectors minted themselves. It was the same with John F. Simon, Jr.’s Every Icon: there were 512 available. These projects used the conventions and mechanics of the NFT drop. I purchased an Every Icon in the original mint because I’ve been a huge fan of this piece for twenty years. I can’t believe I never got the twenty-dollar Java applet it was originally built on. Having one now feels great.

I checked out a Discord after the Every Icon release, and people were wandering in there asking, “What’s the utility?” or “What’s the floor?” Who cares about utility and floor? We bought it because we like it. I have to admit, though, I wonder if I’d be tempted to sell if the price went up. It’s the same for Ornament by Jan Robert Leegte, which like Every Icon is all on-chain. Part of why I bought Ornament is because I like it, and because I follow Jan’s work, but I also thought it would be a good investment. He also used the drop mechanic of a limited edition; once they’re all minted, you have to find them on secondary. These sorts of conventions or methods seem to work well for NFT buyers. The 1/1s are a harder sell I’ve found so far.

Rick Silva’s Antlers WiFi were originally from 2011. He was ahead of the time. He was thinking of gifs as a legitimate artistic medium, which wasn’t that common a decade ago. Now there’s a way to sell those things.

I’m grinding an ax a bit, but in the nineties and aughts—when I was making net art with MTAA—we were oddballs on listservs and at conferences and exhibitions. Most other artists taught or lived in a country with social programs to support artists. Basically no one made money selling their work, but most had some sort of institution supporting them. That was my perception anyway. And now I’m seeing lots of criticism of NFTs from similar people— people who never had to try to make a living from marketing their artwork. That rubs me the wrong way.

Many museums have digital works in their collections, but very little that lives online or was meant to exist on a network. Now you can sell and view networked art exactly as it’s supposed to be through NFTs.

— As told to Lauren Studebaker