The Superflat Metaverse

Takashi Murakami has become a staunch advocate of virtuality. But what gets lost when bodies are left behind?

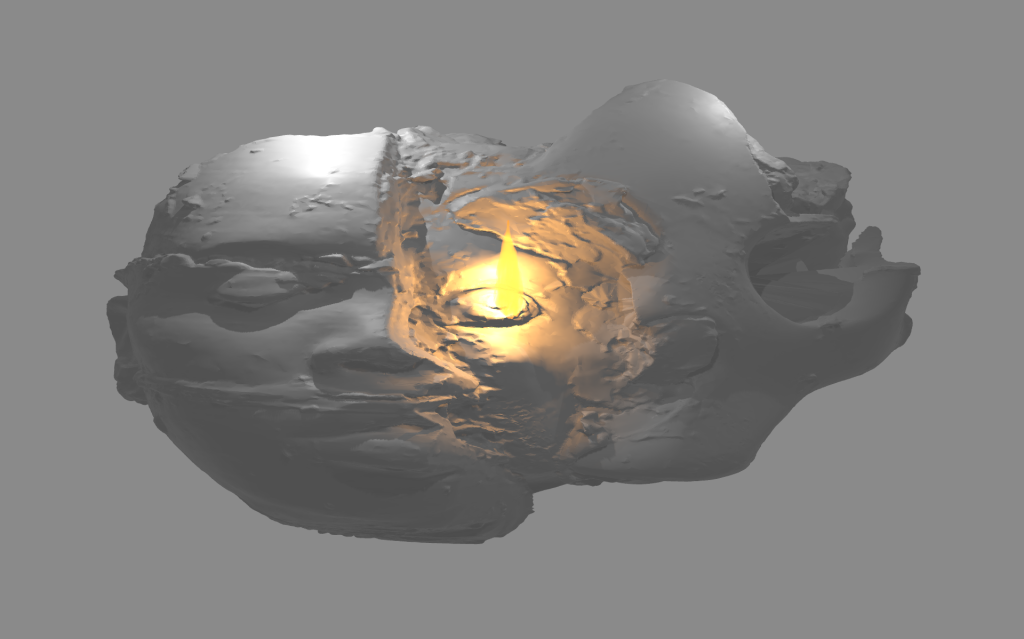

Suspended in a featureless void, Auriea Harvey’s Gray Matter exudes a sullen sense of mystery. The digital sculpture consists of a strange head, seemingly modeled from clay. On one side emerges a woman’s face, her gaze downturned and introspective; on the other, a smooth skull stares blankly into nothing; in the middle, both visages collapse, virtual flesh and bone, or clay, falling away to reveal a flickering yellow flame where the eye should be. This is the only source of color; everything else is shades of gray. The viewer, encountering the sculpture through a phone or laptop screen, can inspect it from all angles. Look underneath, and you discover the smooth cut of the neck at the base. Look above or behind, and the form becomes lumpen and unfinished, the skull giving way to rough, malleable gray matter. And you can manipulate it, up to a point. Click and drag the form and it will stretch or flatten under your touch. The face remains impassive, but stretch too far and its flame snuffs out abruptly.

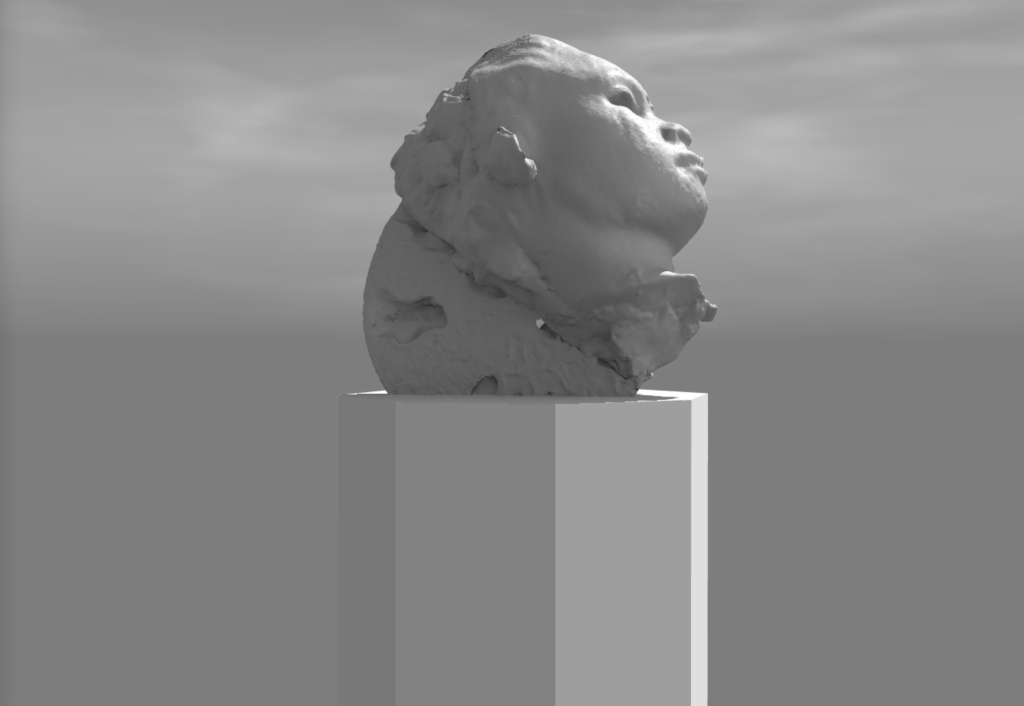

Gray Matter is one of eleven sculptures (all 2022) in Harvey’s online exhibition of the same name, hosted on Feral File. Each bears that same mysterious, hybrid quality—rooted in the long physical and cultural history of traditional sculpture, and yet utterly at home in virtual space. This is unsurprising, given Harvey’s professional background. Trained as a sculptor before transitioning into video game design and then, in recent years, back to fine art, she is a versatile artist, equally adept with physical and digital media and happiest when combining the two. All the sculptures on display here have origins in the “real” world; they are composites, digitally assembled from scans of the artist’s own body, assorted found objects, and physical sculptures and discarded workshop fragments in media including clay, gesso, and 3D printed wood and plaster. They have a physical future, too. Collectors of the work receive not just the digital creation, which is minted as an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain, but also a 3D printable file and a bronze sculpture—solid, richly patinated remakes of their virtual antecedents. (The sale is live until the end of November.) Together, these components form a project that is perfectly designed to break down, interrogate, and reform our expectations of what sculpture is, what it can be, and how we should engage with it.

This transmutation of artworks from physical to virtual states and back again is characteristic of Harvey’s oeuvre. In an accompanying exhibition text, the show’s curator, Gaia Bobò, likens the artist’s methods to traditional bronze casting techniques, through which a work is brought to life—and fundamentally altered—in successive stages, from modeled plaster or wax to a temporary mold, rough metal cast, and polished final piece. With each step, the surface and substance of the sculpture changes profoundly, yet each permutation is vital and linked. The difference is that Harvey doesn’t discard the products of the middle processes; they all have value. But while you can see the legacy of physical media in these digital sculptures—in Gray Matter’s wet-looking clay, in the polished reflective surface of body parts in The Hand-Heart Problem, and in the large fossil shell in Faunette—the real focus here is on the peculiar properties of virtual media. Harvey is interested in the inconsistencies that emerge during 3D scanning and often retains the extrusions in her digital models. She renders her virtual sculptures in polygons, translating a 3D surface into a flexible geometric mesh, and is clearly enamored with the medium, which she describes, in an interview with Bobò, as “sculpted math” with outputs as beautiful as the “facets of a complicated jewel.”

With each step, the surface and substance of the sculpture changes profoundly, yet each permutation is vital and linked.

The sculptures are presented as gray high-poly models without additional surface color—a decision which draws attention to their essential form while also suggesting potential for further development, like digital drawings or maquettes. Inspecting the works, one can’t help but discover the qualities and constraints of the medium. In White Rest, for example, a bulky, elephantine statue rests on a stepped pyramid. Its features, which include two outsized horns topped with a mass of flowers, are pale, their edges picked out darkly like contours on a virtual terrain map. As you rotate the sculpture, they flicker and blur before the graphics resolve again. In Curse Tablet, a strange, hollow sculpture resembling a torso on a classical pillar bounces perpetually on a string. It is described by the shadows moving on its surface—the lit parts merge with the gray background. If you angle your view above the sculpture and zoom in, you can peer into its shadowed depths, until it bounces up and collides with your virtual field of vision, causing details to blink and clip out of view. These are characteristics unique to the digital versions of these sculptures. Rather than glitches to iron out, they are presented as features to celebrate, bringing a certain truthfulness to the medium in the same way one might appreciate non finito carvings in marble.

This approach is particularly interesting at a time when photogrammetry, 3D scanning, and other digital technologies are being hailed for their potential to record and preserve historic art in unprecedented detail—even to create exact “replicas.” Harvey’s sculptures suggest that this is not only impossible—a degree of modification and manipulation will always be necessary when copying works into new media—but also perhaps undesirable. The artist lives in Rome; her work is replete with references to its rich sculptural heritage, but rather than perfectly replicating her influences she hybridizes them. In Faunette, she reimagines the head of a classical faun in her own likeness; in Messenger (Fragment), a disembodied foot is poised to spring into the air with the breath of a zephyr at its heel; in AlleluiaAlleluia, a seraphim-like figure with a wing for a body wheels in space, wielding two glowing crescent moons. The wing in the latter work is from a scan of the Nike of Samothrace, a well-known Greek votive monument now held in the Louvre. It is no coincidence that most of these references take the form of fragments. Fractured, decontextualized forms tend to have a potent yet surreal effect on the viewer quite distinct from their original purpose, and can be recontextualized and reassembled in myriad ways. For Harvey, as for many artists before her, sculpture is a living tradition whose power lies not in its perfect preservation but its constant transformation. Her sculptures are the latest contributions to a centuries-long process of repurposing, reformulating and revitalizing forms and ideas.

For Harvey, as for many artists before her, sculpture is a living tradition.

This is also true of the interactive elements that Harvey has introduced. In Gray Matter, the act of stretching the sculpture destroys the illusion that the work is made of clay. One can imagine parts of the model yielding under the firm press of a thumb or finger, but tapping and dragging its surface elicits a totally different sort of transformation. Messenger (Fragment) blurs as you zoom in, like an unfocused camera, reminding you that you are looking through a screen. The controls can be a little tricky to master, as tapping, dragging, and pinching actions are programmed to affect each virtual environment slightly differently. By repeatedly changing the rules of engagement, Harvey forces us to renegotiate our relationship with the virtual works, making us more aware of the physical actions and interfaces involved, and even of the role our own “gray matter” plays in processing simple pixels and polygons into this strange pantheon of living sculptures.

In Harvey’s work, the process of scanning an object is not to preserve the original, but to unlock its digital potential and open up new creative avenues. Once she has a sculpture in the virtual realm, she plays with these possibilities. “Gray Matter” features unique custom environments for each artwork. Some works hover in empty space; others sit on simple plinths and platforms, under atmospheric skies or in sparse landscapes bounded by low horizons. All the scenarios are impossible in real life, and also quite unlike the majority of “virtual reality” exhibitions, which generally try to approximate gallery settings. The artist also has her sculptures engage in impossible acts. The spindly totem in ba-eye, whose stylized hieroglyphic eye cries animated tears, would be miraculous in a museum. Dagger, a rugged obelisk flanked by the busts of two minotauresses, periodically leaps into the air, flips, and pierces the ground, literally upturning our expectations of monumental sculpture. It would be interesting to explore how sound, for example, could further alter or enhance the character of these works—though its absence, like the absence of color, seems calculated to draw attention to their artifice.

One of the simpler sculptures in the exhibition is called Mumble. It consists of a mask-like face (another of the artist’s likenesses), its left half cleaved away, its lips muttering soundlessly. The caption accompanying the work asks: “What makes something alive in the digital space?” “Gray Matter” is a fascinating meditation on this question. Harvey’s sculptures celebrate the rich potential of digital modeling and display, which can reanimate forms and engage audiences in a new way. But they are also deeply embedded in the physical world, laden with cultural references and personal imagery, and loaded with potential for future transformations. In Harvey’s oeuvre, the life of a sculpture is always changing, its reality never quite fixed.

Maggie Gray is a writer, editor, and art historian based in London.