Skawennati & LaTurbo Avedon

Two artists who make work in Second Life exchange ideas on the meaning of identity in virtual communities, and the prospects for widespread immersion in the metaverse.

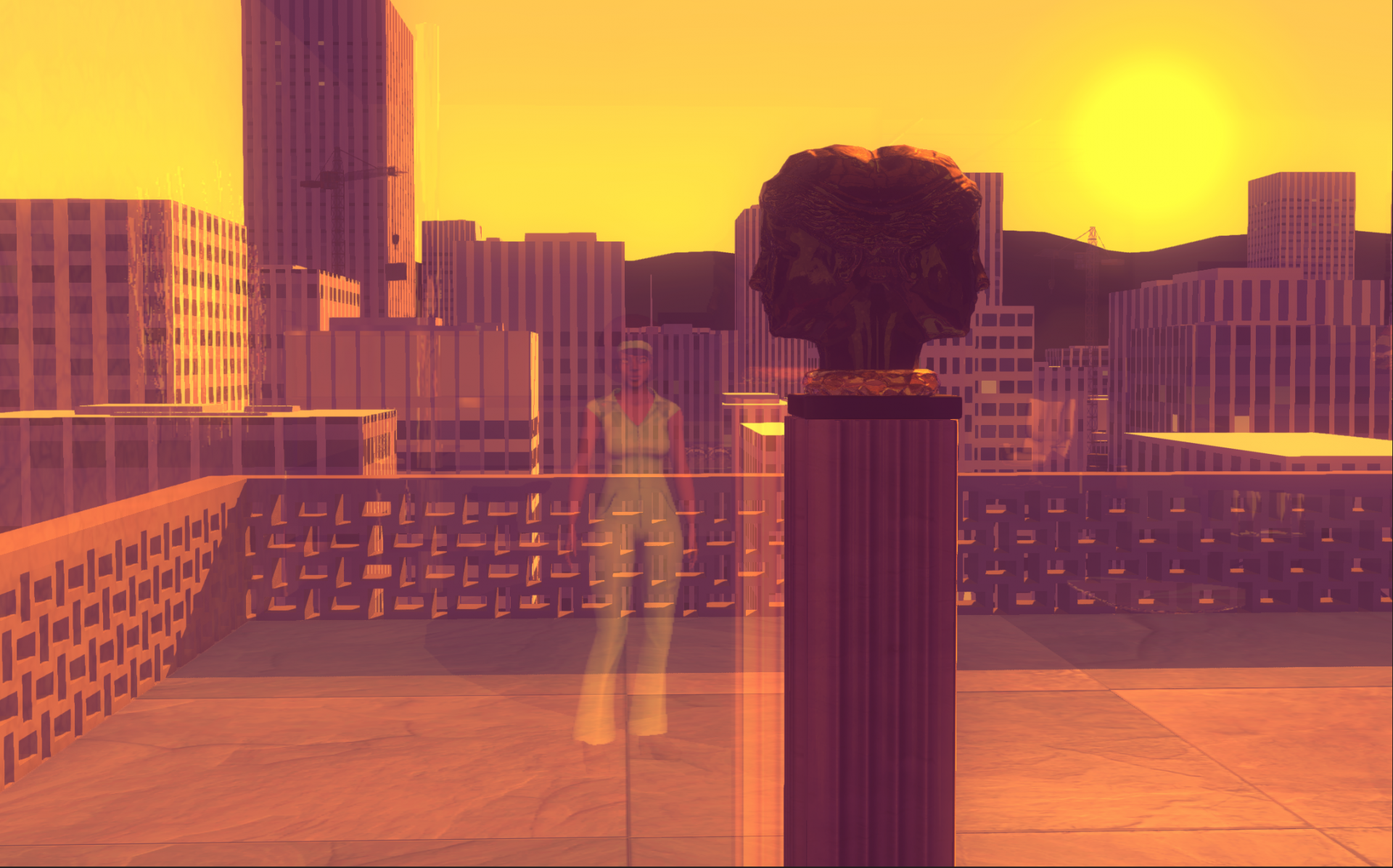

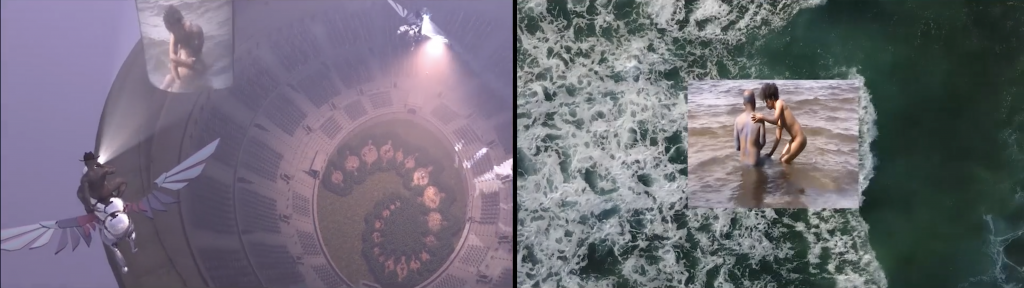

Artists who do the most interesting work with digital media often start elsewhere. Auriea Harvey studied painting at the Parsons School of Design before learning web design and then, with Michaël Samyn, founding the game studio Tale of Tales, which released experimental interactive experiences that expanded notions of what video games could be. Jacolby Satterwhite earned an MFA at the University of Pennsylvania, where he also studied painting, and only after graduation he began teaching himself Maya, which he used to create the engrossing, multidimensional hybrids of animation and video he’s known for today. Both artists still work in multiple mediums. Recently Harvey has focused on physical and virtual sculpture, blending 3D prints with natural materials and building digital models. Satterwhite returned to painting and showed the results in a recent exhibition at MoMA PS1. He is currently building an interactive virtual world for Cleveland’s FRONT International, a triennial that opens this summer. Harvey and Satterwhite met to discuss their shared love of video games, their interest in virtuality as an enhancement of the real, and how they achieved mastery through total dedication to craft.

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE I’ve been playing your games and you are a legend! Your syntax, your eye, your philosophy of turning the nonplayable character into a protagonist—it’s all so important. It bleeds into your sculptures, which give females in art history agency by reanimating their existence with 3D printing. The Graveyard is such a morbid weird mystery game. You have a refusalist style of making interactive experiences where entertainment is not the priority.

AURIEA HARVEY You’re exactly right. It was very much framed that way at the time. The Graveyard came out in 2008. It was actually the first game that we charged for. We did it as an experiment, to see if anybody would play such a thing. But we also wanted to make a statement about this refusal to make a game. We wanted to create a poetic experience, which was a rather rare thing at that moment in game history.

We liked games that had moments or a vibe that stuck with you. We wanted it to be about that vibe, about that atmosphere, about that one particular moment in that one particular game where the old woman is walking in the graveyard and she just goes and sits down and she may or may not live to see the end of the game. And that’s it. Nothing else. That was a big statement about our philosophy. We can make games that enhance people’s lives rather than replace them.

When I was watching the Art21 video you sent me, it was amazing to me how fluidly you go in and out of the real and the virtual, how you pulling yourself into these virtual spaces and then embody those same characters in real life again.

SATTERWHITE Thank you. I think that principle was embedded in me when I was at boarding school. I had a photography teacher who gave assignments about extended frame photography where nucleus of the project sits within a two-dimensional image. But how do you find a way to build a mythology outside the frame? If I’m going to build a world, I’m going to think about this world as a sculpture. I’m going to render the architecture of it twelve hours a day like a dork in my studio. I’m going to do 3D prints for the costumes. I want to embody the character in real life, as a form of method acting.

HARVEY It’s cosplay, but you’re cosplaying yourself as a character.

SATTERWHITE When I was making Birds in Paradise, I was so deeply into making the projects and they were my life and it was the only thing I did, that I became the life that I was describing in the work. I went to Fire Island with a green screen and a backpack full of vintage Helmut Lang leather.I invited porn stars, drag queens, queer friends, and miscellaneous individuals into my hotel room to perform on my green screen. I worked with this archive on my computer every day for years. I rotoscoped the performers’ hands and feet in Maya, so I could parent objects to their body and make them look more integrated in the world. I delved so deep into this body of work that I began LARPing all the archetypes in my films.

HARVEY That’s brilliant. I liked something you said the other day, that I’m worldbuilding as a coping mechanism. I agree with that so hard. I get that from what you’re talking about as well. It’s these layers of fantasy that we put on reality in order to be able to express our true selves. I’m bringing things out of virtual worlds and into physical reality. I’m also putting people’s physical bodies into virtual worlds and trying to make them understand something through all these characters that I’m making up.

I put a lot of myself into every single character in every single game we made. I was the designer and the creative director and the everything. And the creator becomes the creation in a certain sense, too.

SATTERWHITE I was listening to your interview on Barbara London’s podcast, where you talk about immersing yourself in the work. That’s something that I relate to. But 99% of our audience doesn’t understand the labor and intensity and involvement, and how taxing these processes can be. When you log in these hours, it’s not about the audience knowing. It’s about this uncanny poetry that you can get. Your facility for generating forms and ideas is on a level of masterfulness because of your commitment to playing with the material in such an intense way. When you learn how to code, and when you learn how to model or work with lighting—all these systems are so rigorous and intense that, once you start to explore them, the process in itself is elegant and poetic and speaks about the human condition in this weird way.

HARVEY At a certain point you let go of all the technical stuff and you’re able to just really think about the work and what you’re trying to do with it. When I finally got that breakthrough with 3D, it was an amazing feeling, knowing that I’m free to experiment. It takes a long time to get to that point. And people don’t know what it takes to get there. This notion of practice has fallen out of common knowledge. If you just do this thing with your whole chest long enough, you’re going to get it. It’s a beautiful thing. And I think that’s part of what you were trying to do when you were cosplaying so heavily that you became the character.

I’m able to better understand the world I live in by creating virtual worlds or virtual characters and melding myself with them. I think the only difference between us is that for you it’s more of an embodied thing and for me it’s very extrinsic. I create this other thing that says something for me. Whereas you’re just in it. I find that really beautiful. I want to talk to you about Love Will Find a Way Home, the album made with your mother’s cassettes, and the way you used her drawings in Birds in Paradise.

SATTERWHITE What influenced that was playing Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy and other role-playing games that inventory menus with items and weapons. The materiality was so densely mapped out that the world became really believable and poetic, and in a way that I feel Wuthering Heights or some other classical novel could never achieve. These Japanese narrators were putting their whole soul into their games. They’d hire composers to write compelling scores that were four hundred hours long.

That became my template along with thinking about worldbuilder musicians like Tricky and Bjork, and how their concept albums were so rooted in details, like Bjork recording all of the domestic items in her house to make an album about her relationship with Matthew Barney, or Tricky taking lyrics from his mother’s poems after she died of a drug overdose, and having Martina Topley-Bird sing them over a couple of albums.

It was traumatic for me to learn how to draw while my schizophrenic mother was making ten thousand drawings, sending them off to the Home Shopping Network, hoping she would get us out of poverty by inventing something that already exists. To me her drawings felt like the inventory from Final Fantasy—these schematic diagrams of tampons with remote control wheels. I traced them with a Wacom tablet and stylus and made a vector line and extruded the line, made piping. This inventory became the stage of a world where I could implement my own contemporary ideas.

I don’t make work about my mother. I just use her inventory to build my Final Fantasy. The album was commissioned by SFMOMA. I worked with Nick Weiss from Teengirl Fantasy. I split half of my budget with him so he would spend two years with me teaching me about the potential soundscapes that could be made with Ableton and miscellaneous hardware and synthesizers. We would work seven hours a day making serious soundscapes that would be synaesthetically related to what I’m trying to build in Maya. I would return to my studio listening to the demos and trying to model polygons, engineer lighting concepts, and texture-map my scenes in a way that matched the soundscape. It became less about me realizing a concept than allowing the process to create the concept.

HARVEY You can’t avoid that. You have to let it become what it’s going to become. What you made was really touching—a beautiful tribute all the work she did.

SATTERWHITE Your mother was a jazz singer, right?

HARVEY Yes. She was a touring singer. When she had children, she decided she would prefer to stay home with us. But she was pretty well known. We couldn’t go to a jazz festival without them calling her on stage.She took it up again after she retired and had a little band. They sang and played in restaurants. I just loved this aspect of her life. It never had a direct place in my work. But it definitely influenced my thinking about what art is—this notion that she could just get up anywhere and start singing these beautiful songs that so many people have sung before her. It’s a connection to history.

It’s not like your mom, who was making up words and songs. My mother was interpreting. And seeing that act of interpretation, I think, was what stuck with me. I’m quoting things a lot in my games. The Path is a version of Little Red Riding Hood. Fatale is a version of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. The Graveyard is based on a situation with Michaël’s grandmother. She had no fear of death at all. I’d never met anyone who didn’t fear death. That game is about the way that she looked at it: whatever might come is something she was looking forward to. That was something worthy of exploration. Video games are always about death on some level. You die and respawn. But what if death is death in a game? People were so mad when we came out with that game.

We wanted to explore the potential for games to really say something about the way we live. About being an old woman welcoming death, or being a seven-year-old-girl with your whole life ahead of you. All these things came from listening to my mother sing.

SATTERWHITE You were saying she modified songs. There’s a culture of gaming where people make mods. Is that something you do?

HARVEY These improvisations that happen in jazz are very much like that in a sense. But I never was one for making mods, believe it or not.

SATTERWHITE If I did a mod, I’d just take the skeleton. I’d insert an idea on top of the structure of something like Castlevania. I’m obsessed with side scrollers. They look like paintings, or illuminated manuscripts.The side scroller is underrated. The people who made Super Mario Bros. 2 and 3 made gouache paintings on grid paper that were scanned into a computer. And the walk cycles were coded. I have to have my hand in things. That’s what I’ve been struggling with, right now. I had to get it out of my system and do a painting show because that’s my number one passion, secretly.

HARVEY Really?

SATTERWHITE Yes, that’s what I studied in college and grad school. I taught myself digital tools after grad school.

HARVEY That’s cool. But I wish more artists like you would get involved with games. I’m glad you have a passion for side scrollers and can find these parallels between your painting practice and what a side scroller could be. I think that people who love games as is shouldn’t be making them. They don’t have that extra vision. If you make a side scroller, you’re going to bring something that no one has ever seen.

Artists should look at games as a wide open field. Be inspired, but don’t just be a fan. From the beginning, I looked at video games as interactive artworks. Other than that, it was an empty box that I could do anything with. What kind of worlds would I create as a Black woman living in Europe, feeling somewhat displaced? I knew my voice would very different from anybody else’s.

SATTERWHITE I feel you and agree. I am trying to make a side scroller, but I put it on the back burner because I’m making a game for the FRONT International. I got a commission from the Cleveland Clinic, which has a new building in the city’s Fairfax neighborhood. The community there has an exceptionally high rate of health issues such as cancer and heart disease. So they wanted to build this center as a resource for education and free research and medicine, to shift the narrative. But there was some hesitation from the neighborhood because of gentrification. I took on a commission, and we did outreach for two months to 105 residents to make schematic drawings in the fashion of what my mother or Jean-Michel Basquiat did. The prompt was: how do you create your prospect for utopia? For some people it was a Cadillac, others drew city infrastructure and recreational spaces. Some were these heady inspirational quotes. This was during the lockdown, so everyone was looking for a better future.

I hand-traced all the drawings in Maya and made them into full-on objects. I made another data bank. And, I wanted to make this game called Dawn that’s actually similar to your Endless Forest. I wanted to make a simple game where you can walk around this utopia that the residents built. I wanted make an exploratory game about utopia. But I’m still working on it. I’m scared.

HARVEY Making games can be a scary thing. You don’t know if you can finish it. You don’t know if you have the stamina. You don’t know if you’re going to run into some awful technical problem that makes it impossible to finish. But don’t be afraid. You’ll do it.

SATTERWHITE I just finished a painting show at MoMA PS1. The next suite of paintings are mixed reality paintings, where I made traditional, archaic-looking paintings. But you put your phone or mixed reality lenses to them, that triggers a world to come out of the painting.

What scares me about getting so deep into painting right now is that I invested over twelve years into CGI. These mediums are so far apart in their construction that it creates a very bizarre tension. And I want to bend that tension and strain that tension and maximize that tension. I create CGI films in the same way that I make painting. My favorite thing is to do is to model the form and extrude polygonal planes and color them with a neutral gray, a neutral pink. And put a Mental Ray light on top of it to give it a chiaroscuro Caravaggio effect. How were images built in classical painting? And how does Maya give me the tool set to replicate that?

HARVEY I get it. I’m surprised to hear that you were a painter first. That’s pretty interesting, actually. I went to Parsons School of Design and I thought I was going to be a painter. But I got there in the late ’80s and everybody was like, “No one’s painting.” So I gave it up. My whole career has been this sequence of giving things up and then rediscovering them. But painting is something that I never went back to.

Drawing, yes. I went back to drawing really heavily, to the point where I feel like that’s the third element of my practice. But my drawings are very different from everything else. It’s very tight and more about this notion of a practiced hand technique. In other words, I feel you on the idea of returning to an older look to things. This Caravaggesque notion of light and shadow—I understand that completely because a lot of my drawings are based in the Baroque or even earlier periods. I’m often looking at Hellenistic sculpture. Things that are very old. Primarily, I’m looking at things that are before photography in a sense, because I’m looking for forms that are not influenced by the photographic sense of what a human looks like. So I’m looking at those sculptures trying to see who people were before we had that camera in our head.

I’m always doing a lot of 3D scanning, which is a kind of photography. But at the same time it’s not. It’s this in-between thing. I see it as pulling myself or someone else into a timeless space, rather than capturing a moment.

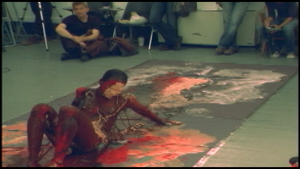

SATTERWHITE I relate entirely with you. In 2017 through ’19, I did mostly sculpture, actually. I scanned my head and put it on these figures that I modeled in Maya to recreate Caravaggio’s Doubting Thomas composition. But I did these performances in grad school where I’d print out these Xeroxes of the SARS virus and the HIV virus, because the viruses looked so painterly and crazy. And I Xeroxed a runway across this corridor. And I staged a performance where I put flesh-tone acrylic paints on the edges of the line.I was naked. I used my body as a redaction tool. So, my body was like an antibody and I just dragged my body down this paint. I didn’t know what to do with this video for years. When I made the sculpture, I hired someone to code the video into loops. And when you walk up to the sculptures you can see the video in the wound.

I was thinking about what you were saying about the difference between digital and sculpture. My point of view is that when you walk around the sculpture, that’s virtual reality.That’s a time-based experience. And it compliments what’s inside of the film. There is a dialogue happening there and that was a breakthrough for me. I featured that sculpture in a film later. But I tried to experiment with other 3D printed mythological characters from my world and embedding. I made a late Picasso Demoiselles d’Avignon but with Grace Jones figures.

HARVEY Man, you’re so busy. It’s amazing how much you’re doing.

SATTERWHITE I feel so much gratitude about that, actually. I used to be stressed. But now I feel fine. I would be in a really bad situation in life if I didn’t have these vignettes to explore. I feel like it’s good for my mental health, my physical health. I have to work out and exercise and take care of myself in the morning in order to be ambitious. My commitment to my work keeps my body sound and my mind sound. And my relationships with my friends sound. Art is my number one love, and I have to love myself and others in order to preserve it.

HARVEY I’m going to try to remember this also. I’m newer to this than you are. I’ve done a lot of things in my life—from net art in the 1990s to making games. Now for the first time I’m really trying to embrace fine art. I used to think I would be doing that my whole life, but life took me all kinds of places.

SATTERWHITE I wanted to talk about your game Sunset. It’s like fine art. The idea of the nonplayable character having narrative agency, cleaning up a house and making discoveries—no one does that.

HARVEY This game is the last one we made. It was when we finally knew what we were doing. But we felt like we had said all that we could say in the form of the commercial video game. I’ve given whole two-hour talks on this game because it was so deep. It takes place in the 1970s—a period that my husband and I barely remember. But we have these weird memories about the ’70s so we decided to investigate that. I put in things about the Black Power Movement. We took the floor plan of the apartment that was in the January 1970 issue of Playboyas the perfect bachelor pad. We made that into the apartment that the game is set in.

So it was this perfect melding of things that we both wanted to explore. But this game was complicated because it had too much in it. It’s about revolution. You’re in a fictional South American country. You never meet the protagonist but you have to learn everything about him. It was the ultimate test of our game-making skills. I’m extremely proud of that game, even though it’s trying to do a little too much.

SATTERWHITE So interesting.

HARVEY I’m glad you were attracted to Sunset. Because it was a tribute to everything that I love, in a sense. It had this notion of, and the speculation of, what if we lived in a different world where even though you are the house cleaner, you can stop a war. I like to believe that that’s possible, somehow.

SATTERWHITE Playing it anchored my intention for what I’m about to do with my own work. So I want to thank you for that because I was literally dragging my feet with the games that I’m developing. I like your refusalist mode, how you allow things to be. That made me feel OK with the things that I’m trying to do, because I feel I was expected to do something else.

HARVEY You should follow your instinct and see where it leads. A lot of people start approaching games and they think it’s got to be a certain way. But you can make a game that is all the things that are inside you. We once tried to make a game that was about everything. And we failed. It was about the universe outside and the universe within—the movements of stars but also chakras, the connection between people and the connection between worlds, sex and intense emotions as well as traveling in space and time. It didn’t come together, and it actually ended up being two different games: Luxurious Supurbia, which was our sex game, and a small vignette called Lock, which was about the universe. But these two things were very small compared to what we were trying to make.

What I’m saying is, a game can be all those things. You are the only limit. You’re the block. You’re the one who has to decide where the limits are on that in order to accomplish something. It’s something I had to learn the hard way—to make not one game about everything, but two games about different aspects of the thing you’re trying to accomplish.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour