Golden Hour with James Jean & DBA

Highlights from our Golden Hour event, where friends of Outland, Vera the Ape, and James Jean gathered to celebrate the opening of Infinite Museum.

Rather than make our own selections for the best digital art of 2023, we asked five of Outland’s guest editors—from Sarah Zucker, who edited our first special issue at the end of 2022, to Mitchell Chan, who is planning our first issue of 2024—to share their highlights with us. Their picks cover a wide range of activity: on-chain experiments, augmented reality installations, and browser extensions. For more information on the contributions of our guest editors to Outland this year, you can read an overview of our special issues.

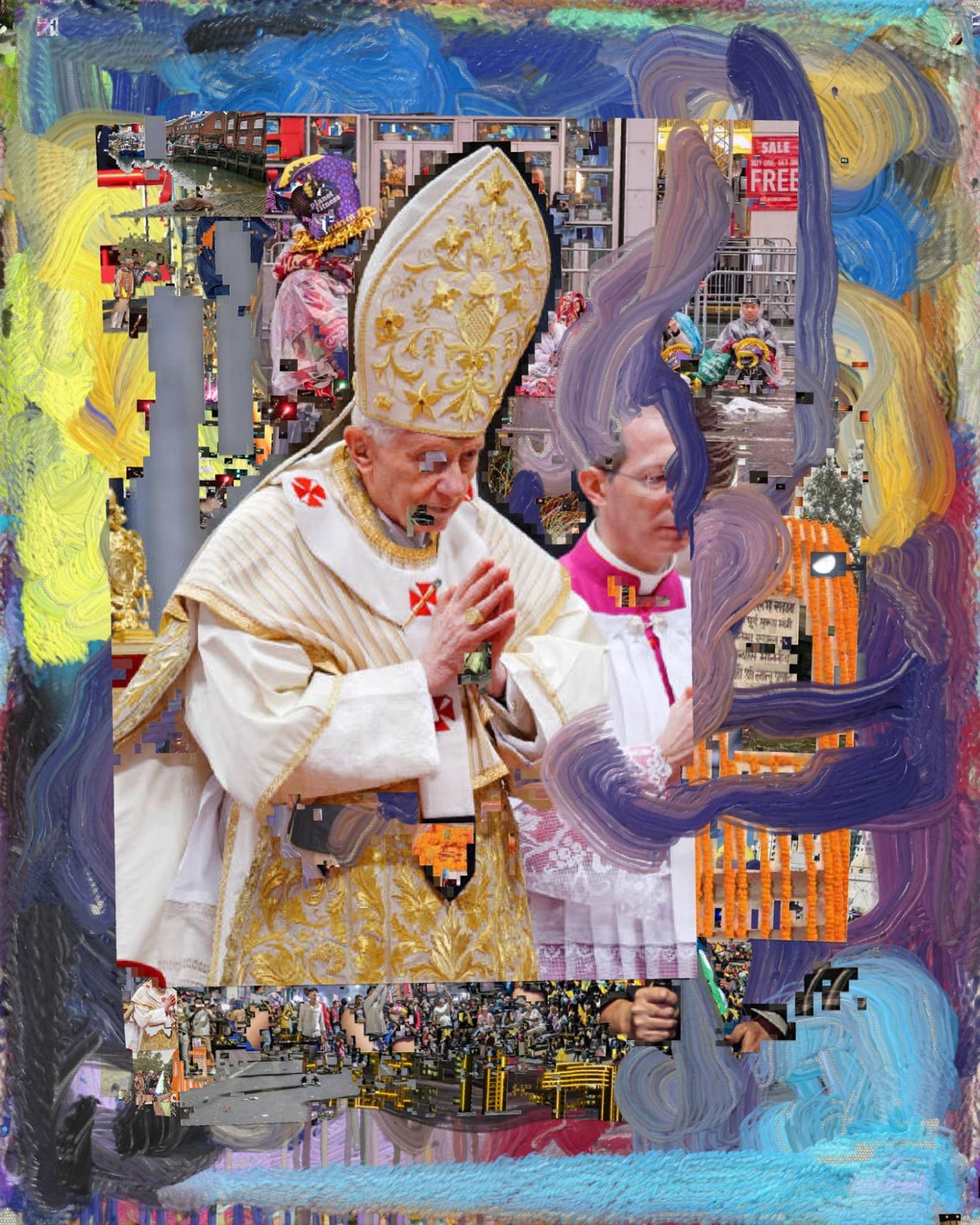

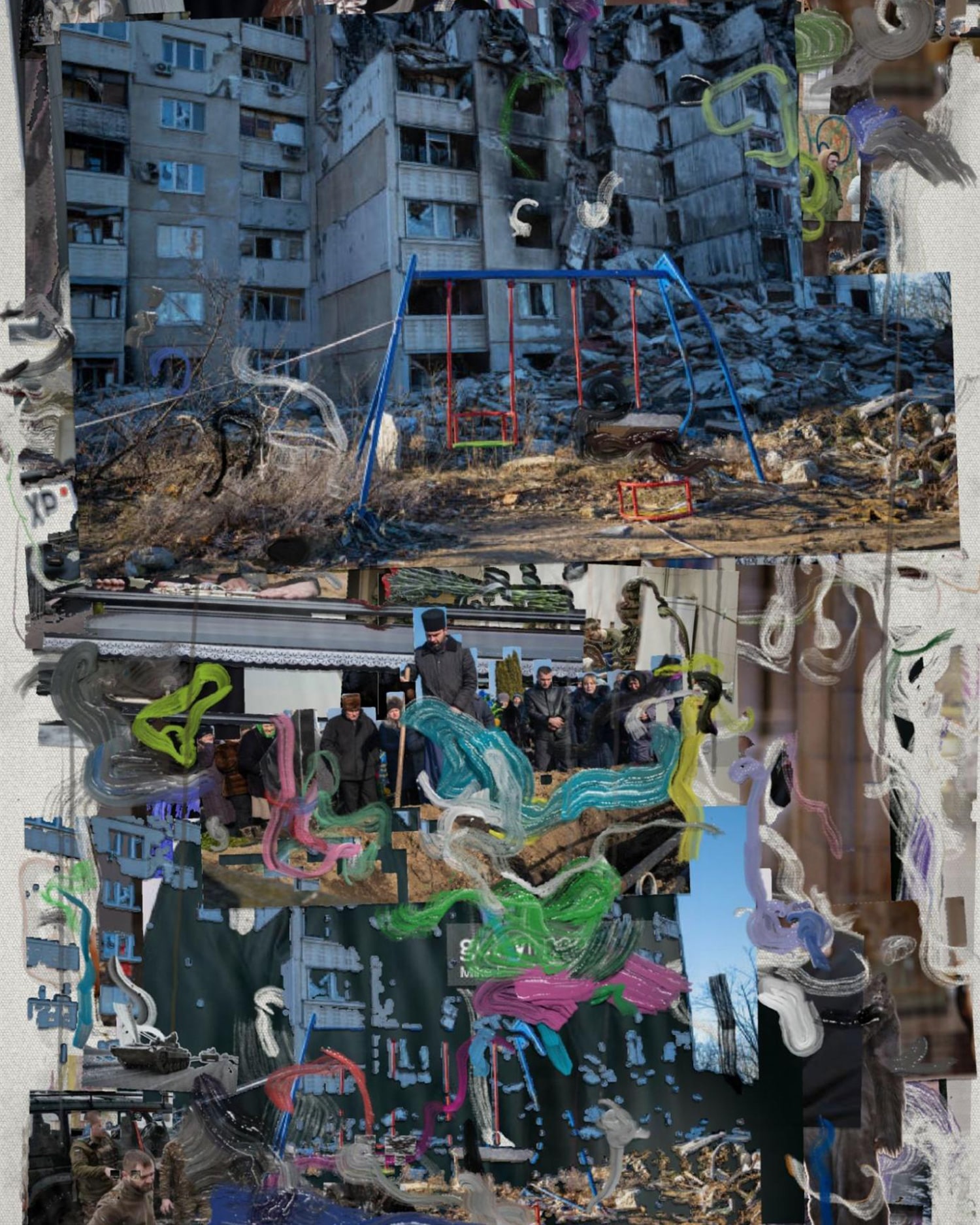

I found Siebren Versteeg’s For a Limited Time, released on Arsnl Art, to be one of the most interesting series of 2023. It incorporates the mechanics of blockchain editioning into the artwork itself—and the outputs are both aesthetically compelling and conceptually potent. Throughout the year, Versteeg’s algorithm generates a new digital collage based on current trending headlines every ten to fifteen minutes. By allowing collectors to claim which collages to imprint on their edition (and, conversely, which collages will remain unclaimed and then vanish), the project elevates interactivity beyond a sales gimmick and into the sublime realm of collective meaning-making. The collages themselves are striking and often surprisingly poignant in their clustering of headline text, imagery, and digital paint. As a rare long-form project, it has pulled me back repeatedly throughout the year to check on its unfolding. I’m eager to see how it will stand upon completion, and the narrative of this time that will emerge through the collaboration between the artist, the algorithm, and the collectors.

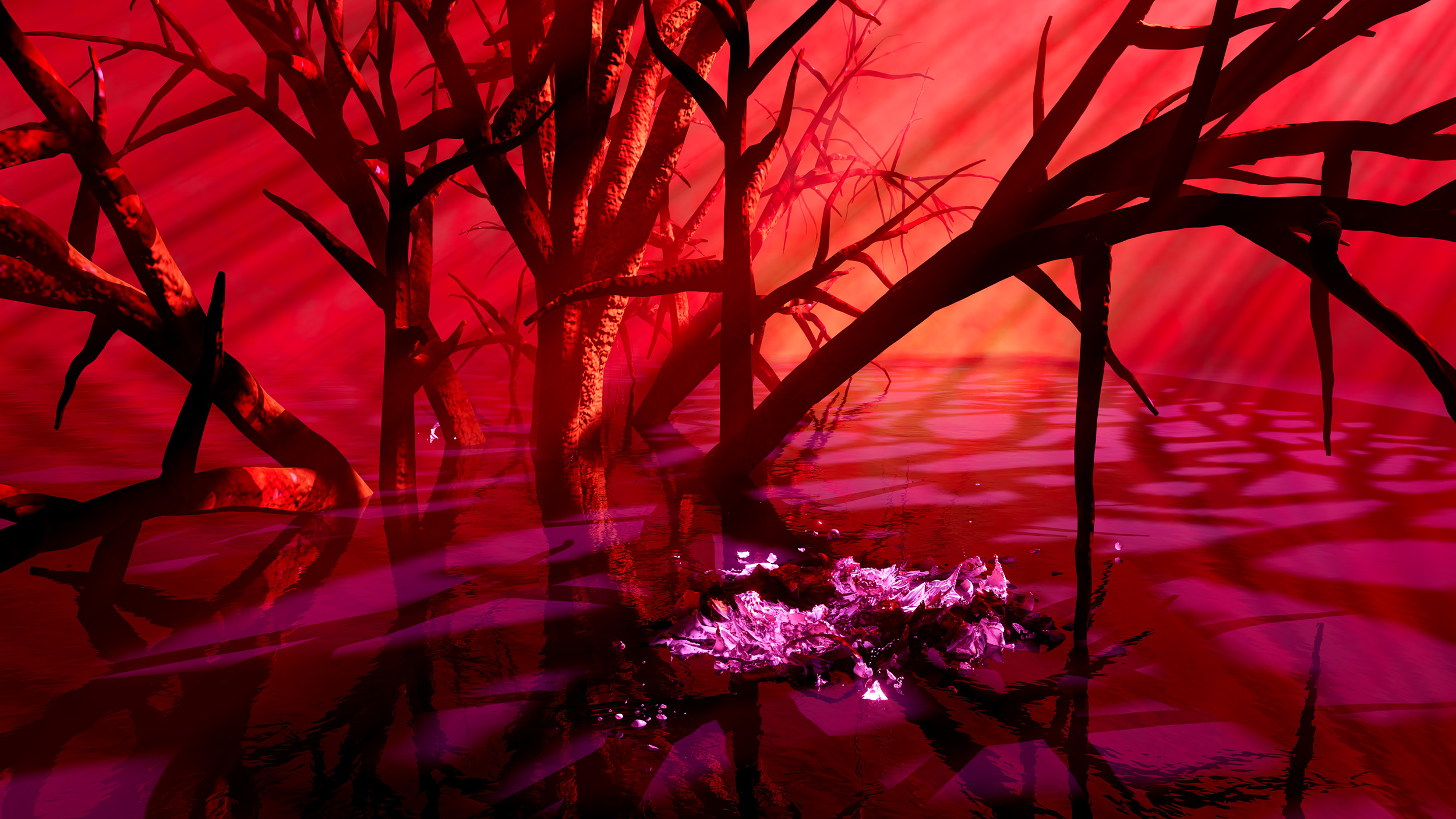

Nancy Baker Cahill’s “Cento” opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art on October 3 and was an immediate sensation. An augmented reality creature that floats above the museum terrace, the work extends Cahill’s use of fiction to generate transformative works of digital art. But Cahill released a slightly lesser-known work earlier in the year that really caught my eye. The quivering and lively nerve of the now is an homage to Brazil’s most important and most experimental twentieth-century writer, Clarice Lispector. This digital video tunes into the mediumistic vibe of Lispector’s book Água Viva (1973) by reveling in what Cahill refers to as an “abstract carnality” that counters “this moment of contemporary witch-hunting and politically sanctioned misogyny.” Like me, Cahill has a huge artist crush on Lispector and does everything in her power to create a work of art that summons the hidden depths of an imaginary language beyond the language we think we know.

Equally focused on language but through the lens of speculative fiction, avatar-otherness and persona-making, Carla Gannis presented her exhibition “wwwunderkammer” at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina, this summer. The project originally appeared in a smaller form at the Telematic Gallery in San Francisco in March 2020, but that show closed five days after opening due to Covid. This year’s extended play remix was inspired by The Blazing World (1666) by Lady Margaret Cavendish, the first known work of speculative fiction by a woman. The cabinets are lined with prints of AI-generated abstractions, trompe l’oeil imagery that teases the 3D sculptures accessible through AR. Gannis has transformed her AI alter ego C.A.R.L.A. G.A.N. into a work of art, and like the many components of “wwwunderkammer,” she too resists categories that are stabled or resolved.

Some 2023 highlights for me were more art-adjacent NFTs coming to visibility, sophisticated gallery and museum exhibitions presenting digital work, and serious art-historical reassessments of early website and AI work. Jill Magid’s Out-Game Flowers, launched on Artwrld in February, was a standout in the first category. Magid’s digital bouquets of flowers reproduced from several classic video games—gathering and arranging “nature” from many metaverses, and deploying them as grouped assets—felt simple and moving. Other NFT projects that resonated were Folia’s Viper-486 by Billy Rennekamp and Joon Yeon Park, which utilized an innovative update of a Cryptokitties-like mechanic for NFTs, whereby various snake NFTs can “bite” other snake NFTs, making the biters grow longer, and simultaneously producing a certificate-of-bite NFT in the receiver’s wallet.

AFK, Josh Kline’s mid-career survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York showed some of the best object-meets-digital work, with his now classic 3D-printed branded body parts poignantly on their way to a dumpster or a Fedex. Afterall Books published an excellent reassessment of Donald Rodney’s incredible web and CD-rom chatbot AI piece and self-portrait, Autoicon (2000), by curator Richard Birkett. Among the many crypto closures this year, a special piece of NFT curatorial infrastructure, María Paula Fernández and Trent Elmore’s JPG closed its doors. It leaves behind an experimental legacy of attempts to add other metrics than price for determining value in NFTs—something I think is still a problem worthy of capital and capacity allocation in order to keep enriching this nascent space.

For someone who has been involved in digital art long before the rise of NFT, this year has been interesting because the scene has become more and more about the art and curatorial movements and less and less about speculation and PFPs. One stand-out project was Mitchell Chan’s The Boys of Summer. It came at a moment when people were taking things so seriously, or were so down about everything. Mitchell completely shifted how people were thinking. It was fun and kind of ridiculous but also smart and clever and conceptual, and used the blockchain in an interesting way. It brought some of the fun back into the space that I feel had been lost.

There are a few other drops and projects that I thought were spectacular. Paul Pfeiffer’s Vs. with Artwrld was an interesting statement on the space. MoMA’s Postcard project was brilliant and informative and again used the blockchain in a new way. The “FEMGEN” show by Vertical Crypto Art with Artblocks and Right Click Save was important because there had been such a lack of focus on female generative artists. Dina Chang’s curated sale for Sotheby’s “Glitch: Beyond Binary” also did a great job of showing how glitch has been representative of multiple different communities. And lastly, “Market Makers” at the Berliner Volksbank eG by María Paula Fernández—I admired the curation and breadth of artists as well as the context itself, the staging of the show in a bank.

Most of my best experiences looking at digital art in 2023 came through ArtTab, a Chrome browser plug-in. Each time I open a new browser tab, I’m presented with a different digital artwork, in its natural presentation format, mercifully free from the framing of a moonboi Twitter thread or marketplace interface. The playlist of artworks on offer is hand-curated to reflect a specific and deliberate taste, with “European Fine Art NFTs” in heavy rotation. Sometimes ArtTab will immediately hypnotize me for minutes, making me forget whatever I was supposed to be doing. Sometimes I’ll leave a tab open all day, so I can come back to the same artwork again and again. It’s obvious, I realize, to acknowledge just how much one’s flagging enthusiasm for NFT art can be rekindled simply by stripping away the toxic context of NFT culture.

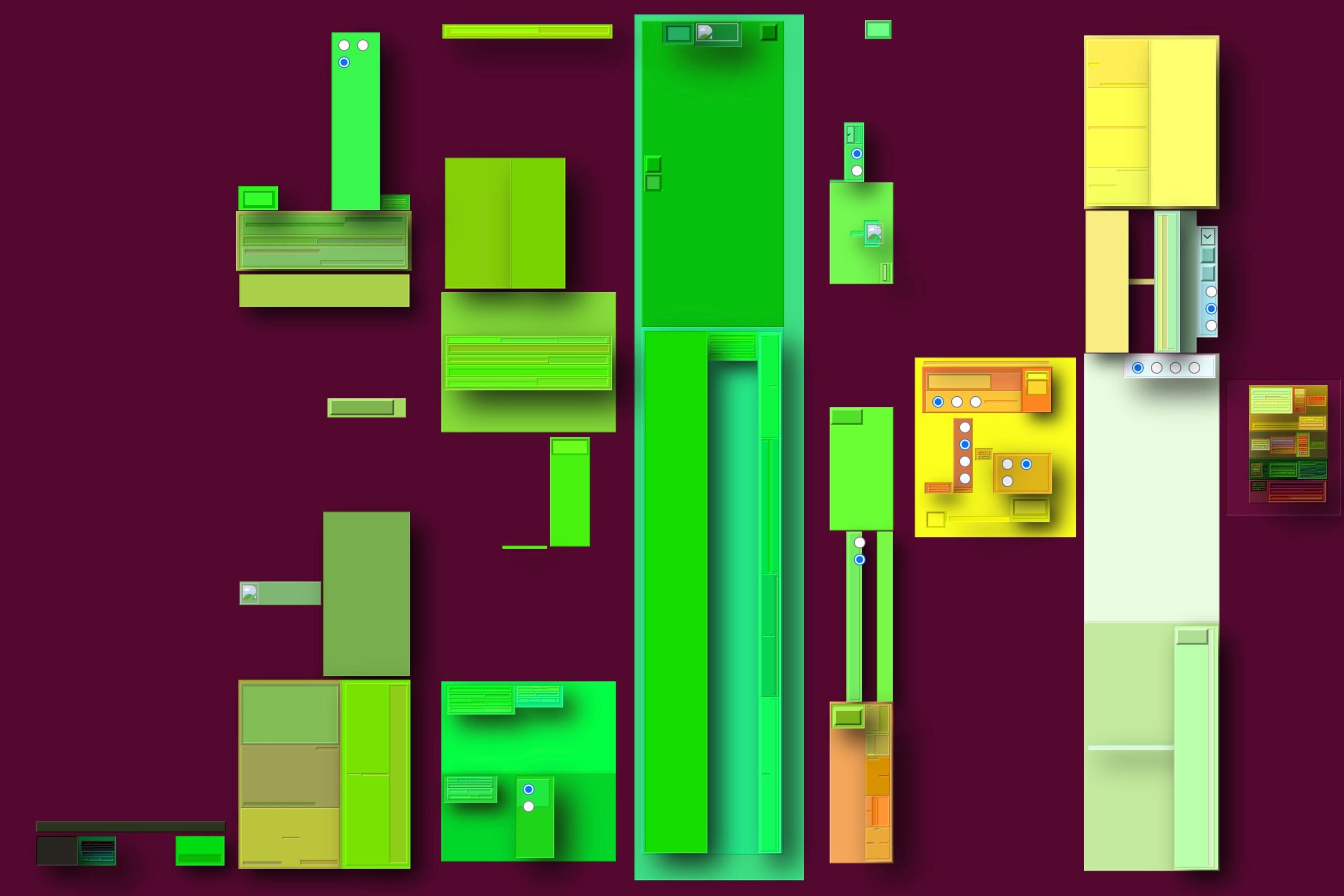

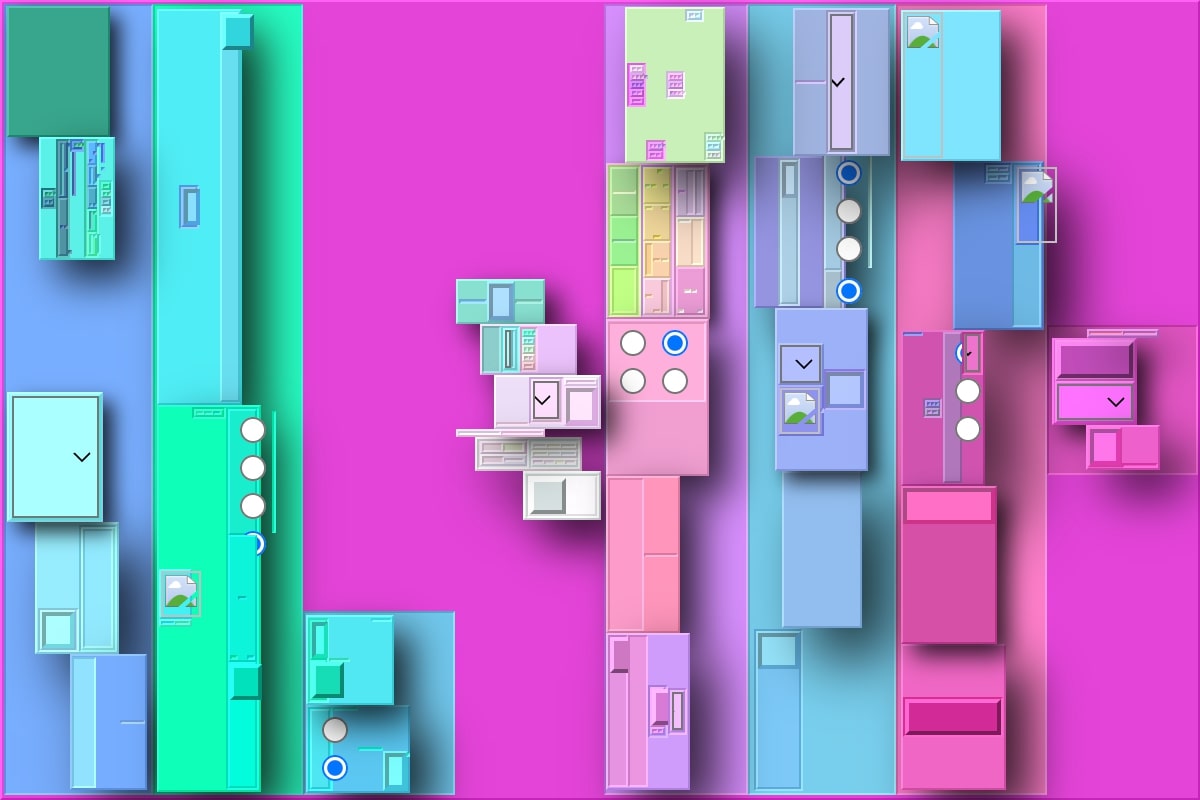

Speaking of context and browsers, one of my favorite projects of 2023 was Jan Robert Leegte’s Web. Like much of Leegte’s previous work, Web artfully composes HTML buttons, radio fields, and other hidden-in-plain-sight GUI elements that frame our digital experiences. In Web, however, Leetge takes his context-sans-content approach a step further by adding connectivity. In Web, each button is a functional link to another work in the series. The result is an acerbic portrait of the internet: a tightly connected network of structural forms without content, with each artwork serving as a context for the next.