Lenses on Glitch, Part 1

Four artists share the tools and approaches they have developed for working with glitch.

The Bitcoin blockchain was made to record transactions, not messages. Relatively recent changes to the Bitcoin protocol support the creation of Ordinals, or Bitcoin NFTs, but there is also a history of scrappier, clandestine inscriptions that goes back to the very beginning of the blockchain. There are jokes, poems, conspiracies, links, and ASCII art forever embedded in the logs. These messages that pre-date ordinals are primal and haphazard—they already give an air of the archeological. They are also, unlike NFTs, the result of the creative misuse of a technology.

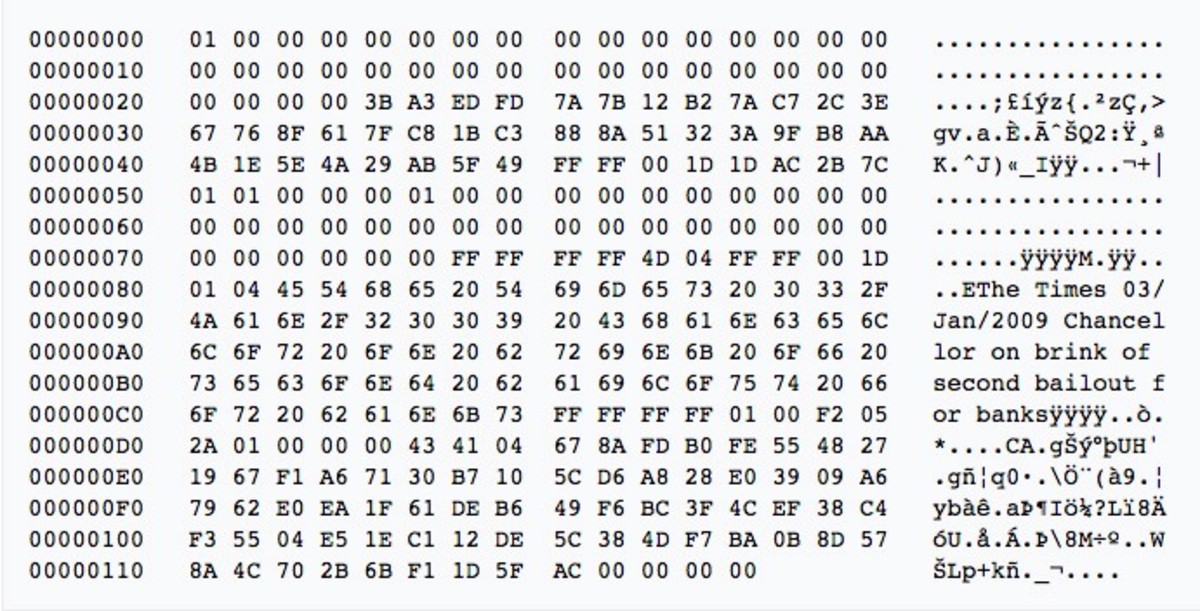

“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks” is inscribed in the genesis block of the Bitcoin blockchain. The message from Satoshi Nakamoto, the anonymous person (or group) who conceived and initiated Bitcoin, is at once clear and cryptic. It’s a headline from a British newspaper, The Times, reporting on the bank bailouts happening in response to the financial crisis at the time. This inscription of bailout news as extra text in the transaction record seems to hint at the desire for an alternative financial system—which is precisely what Bitcoin was supposed to be. Even with the cryptocurrency’s prices recently reaching an all-time high, the success of that endeavor is still a subject of debate. However, the genesis block also initiated a quest for something that gets lost in the shadow of Bitcoin’s fluctuating market: the creation of a record that’s both digital and permanent.

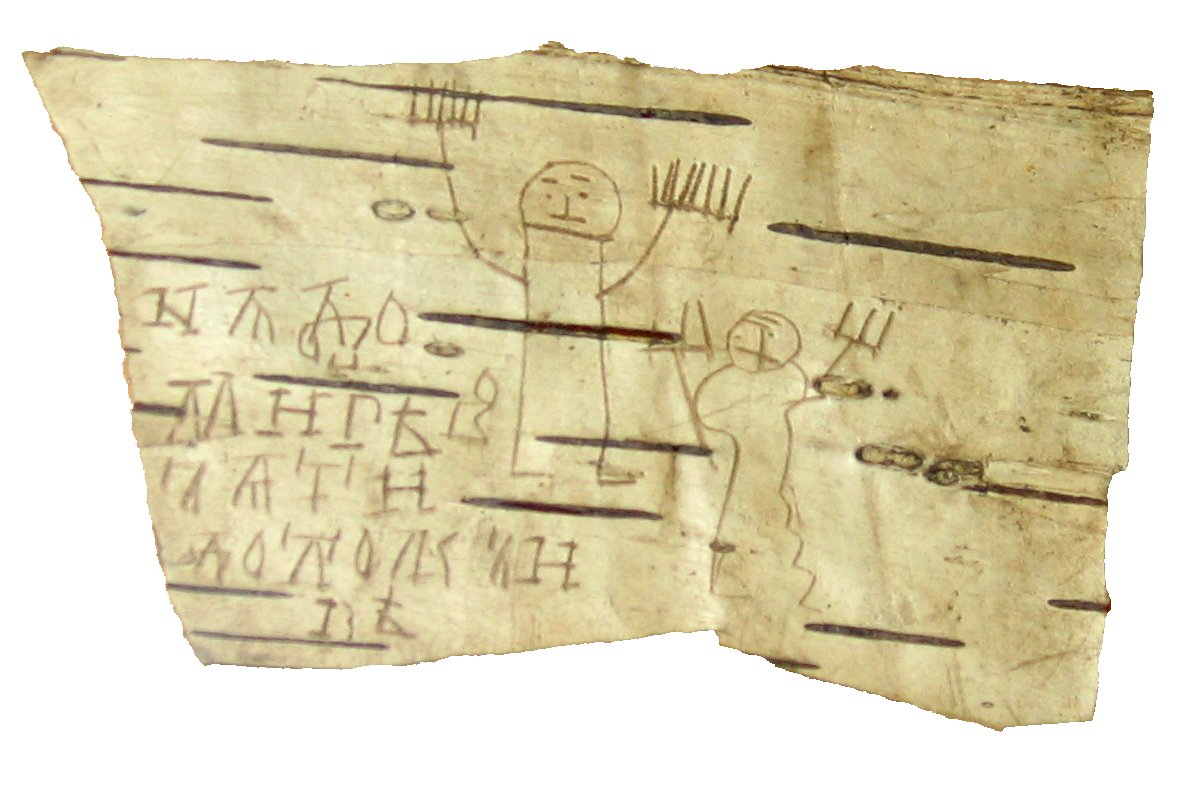

An odd feature of archeology is that mundane artifacts and messages can gain profound significance not because of the content they convey, but simply by virtue of having survived for a long time. An equation could be formed: prosaic expression + permanence + time = profundity. One can think of examples like the c. 1750 BC complaint about low quality copper ingots, immortalized forever in a Sumerian cuneiform tablet. Or the eleventh-century graffito etched into a pillar in Hagia Sophia where a Viking, apparently named Halfdan, wrote simply, “Halfdan carved these runes.” Clay and marble often survive centuries, but even scraps of birch bark proved resilient enough to hold the whimsical drawings of an eleventh-century Russian boy named Onfim, who imagined himself fighting dragons instead of practicing his grammar. Yet when it comes to digital messages, the equation is complicated by the fact that digital storage methods, and almost everything on the internet, are notoriously ephemeral. Bitcoin, and all the other blockchains that came after it, are a wager that the monetary value of maintaining a permanent ledger will ward off the entropy of digital decay. The durability and immutability of the blockchain is essential for financial transactions, but it also creates the tantalizing possibility of something else: digital stone, a matrix that could carry a message forever.

An equation could be formed: prosaic expression + permanence + time = profundity.

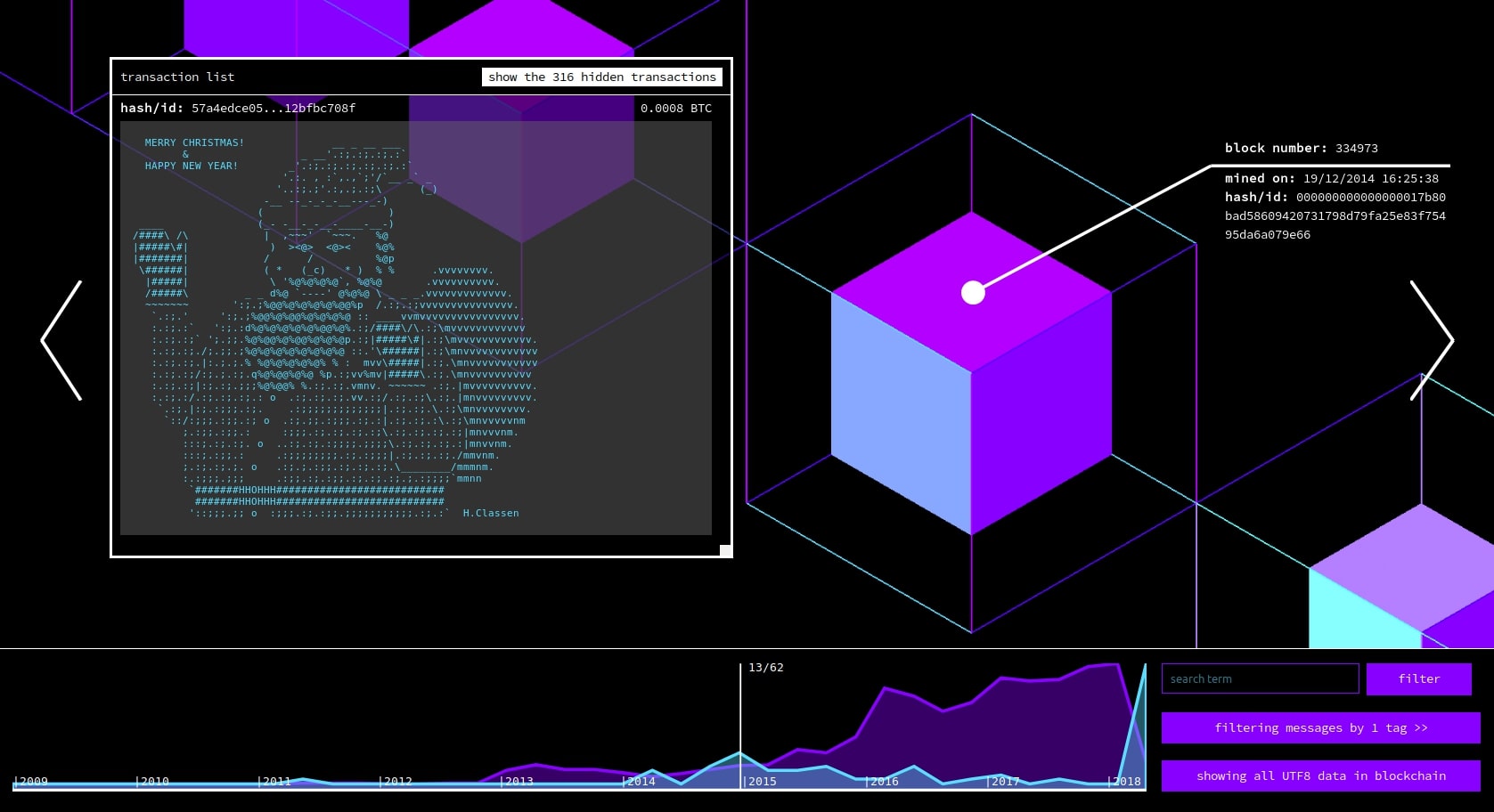

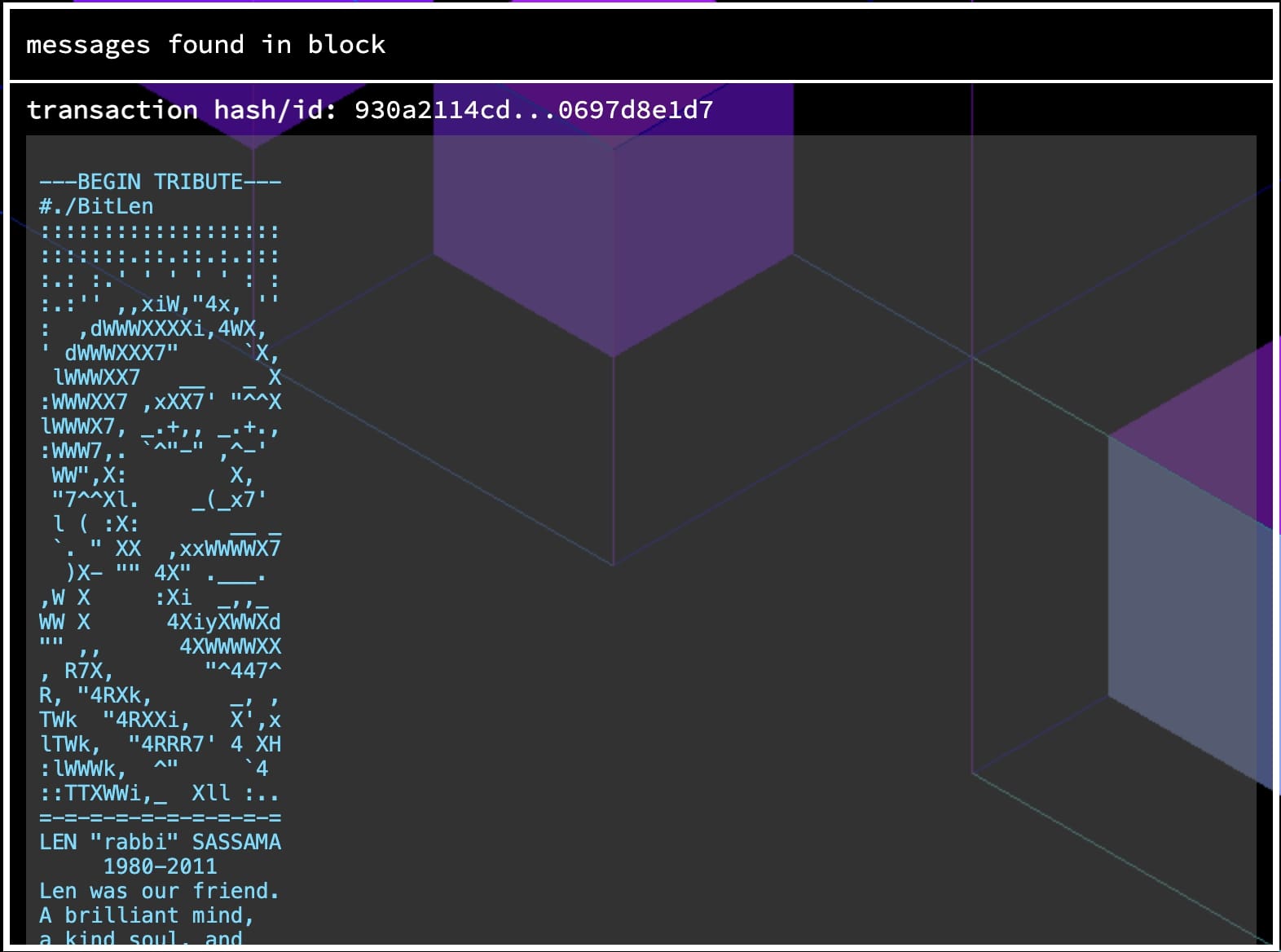

In the first decade of Bitcoin, the allure of digital permanence led to the creation of thousands of short inscriptions buried in the blockchain. In 2018 a Florida design agency called Branger_Briz produced an interactive installation and website dedicated to cataloging these inscriptions for the purpose of anthropology and media archeology, called Messages From The Mines. The archive only goes through 2018, but it allows users to search by keyword and filter based on a number of categories. Branger_Briz has annotated many inscriptions with helpful explanatory text. Not unlike the message left by Halfdan, most messages are simple signatures from Bitcoin miners, like the second message ever, inscribed two years after Satoshi’s headline: “Eligius.” Many mining signatures contain Latin prayers, such as “Benedictus Deus. Benedictum Nomen Sanctum eius” (Blessed be God. Blessed be his holy name). There are also prayers in English or other languages. A message from July 30, 2011, is the first instance of ASCII art: a tribute to Len Sassaman, a cryptographer who had recently died. It contains his ASCII portrait, a short eulogy, and an ASCII portrait of Ben Bernanke, who was then chairman of the Federal Reserve. There are plenty of 2010s meme references (“I LIKE TURTLES,” “ALL YOUR BLOCKCHAIN ARE BELONG TO US,” etc.). In 2016 there was a rash of PizzaGate references, along with plenty of other conspiracy theories, insults, and abhorrent antisemitic messages. There are links to Wikileaks documents, named accusations of Slovenian organized crime rings, and scores of other sensitive and anonymous messages.

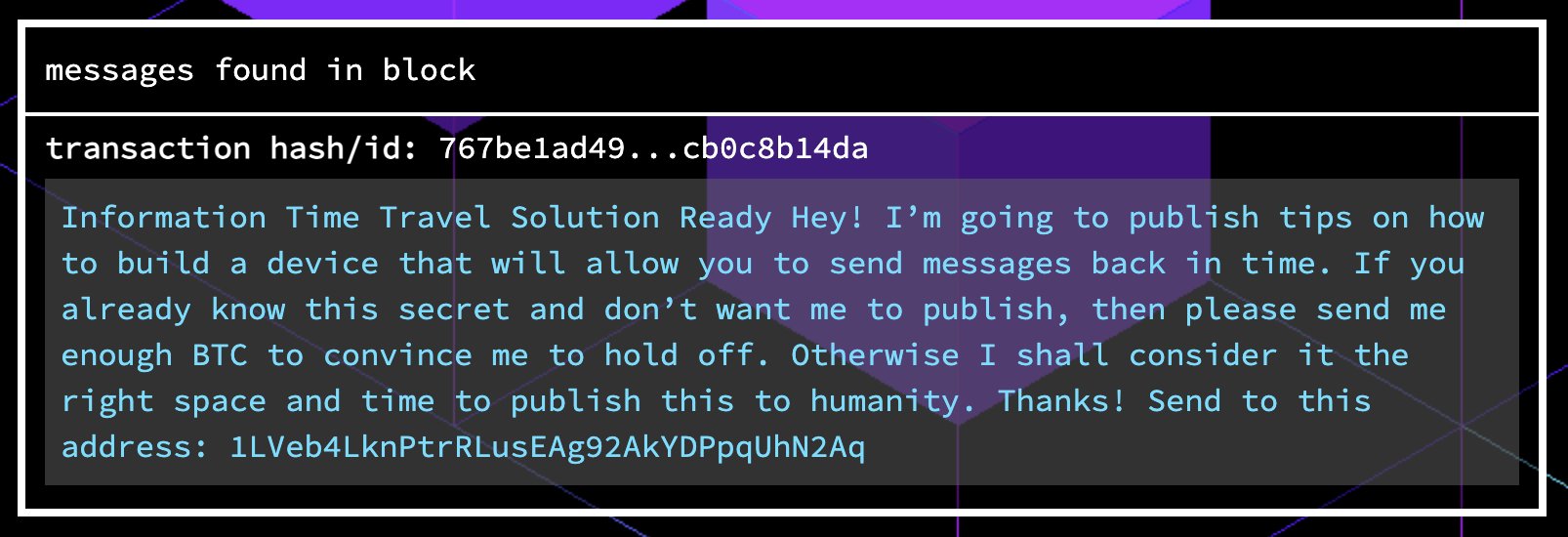

When Messages From The Mines was created, about 11,000 intentional messages were found in the 520,000 blocks that existed at the time. Unsurprisingly, most of them are junk. The most intriguing one I found was a short paragraph in which the author threatens to share a secret method for sending messages backward through time. “If you already know this secret and don’t want me to publish,” the apparently tongue-in-cheek inscription explains, “then please send me enough BTC to convince me to hold off. Otherwise I shall consider it the right space and time to publish this to humanity. Thanks!” The message concludes with an address that a Bitcoin payment could be sent to. There is no follow-up message, so we’re meant to infer that someone else did indeed employ this time-travel messaging technique in order to transfer Bitcoin to the inscription’s author, thereby keeping the secret safe. It’s a joke, but a clever one—a nod to the idea that whatever is included in the Bitcoin blockchain will remain there forever, a kind of time-traveling message that goes only to the future.

Compared to the elaborate creations that are possible using Ethereum and other more versatile blockchains, the pre-Ordinals inscriptions on the Bitcoin blockchain can seem mundane. Their romance, however, lies in their continuation of graffiti in the most ancient sense of the word: mark-making where mark-making is not normally permitted or anticipated. This kind of creative misuse is particularly hard to carry out in digital spaces, because everything on a computer is a program or an app or a function. Artists make images with Photoshop or Unity Engine or MidJouney because these are programs written for the purpose of image-making. Writers use Microsoft Word or Google Docs or Final Draft because those applications were designed for that purpose. Even code is mostly written within platforms designed for a particularly narrow type of creation. The creative misuse of the Bitcoin blockchain is a rare example of making a mark in spite of the purpose of a program, rather than in service to it. This logic does not apply to Ethereum NFTs, even the ones that are brilliantly designed to work on-chain or accomplish other novel things. Ethereum, from its founding, was intended to be a blockchain that fostered the creation and exchange of more than just a digital currency. Its versatility makes creative misuse nearly impossible because it was designed to anticipate creative uses.

Bitcoin inscriptions are a testament to the persistent human desire to leave lasting marks wherever we are.

Bitcoin inscriptions—and, later, Ordinals—are a testament to the persistent human desire to leave lasting marks wherever we are. Inscriptions are also proof that nothing can ever maintain a single purpose. Bitcoin wasn’t designed to be versatile, but users (including its creator) made it versatile. People make inscriptions on the Bitcoin blockchain in a bid for permanence, but the fact that inscriptions are possible, and the evolution towards Ordinals, shows that the blockchain is far more mutable than it was ever supposed to be. Bitcoin’s supposed permanence and its hedge against digital entropy are vulnerable not only to outside forces like regulators, but also to the shifting whims of the community that uses and maintains it.

Kevin Buist is a critic, curator, and filmmaker living in Grand Rapids, Michigan.