Lucid Dreamer

Sara Ludy’s art explores the often unnoticed points where physical, digital, and imagined spaces meet.

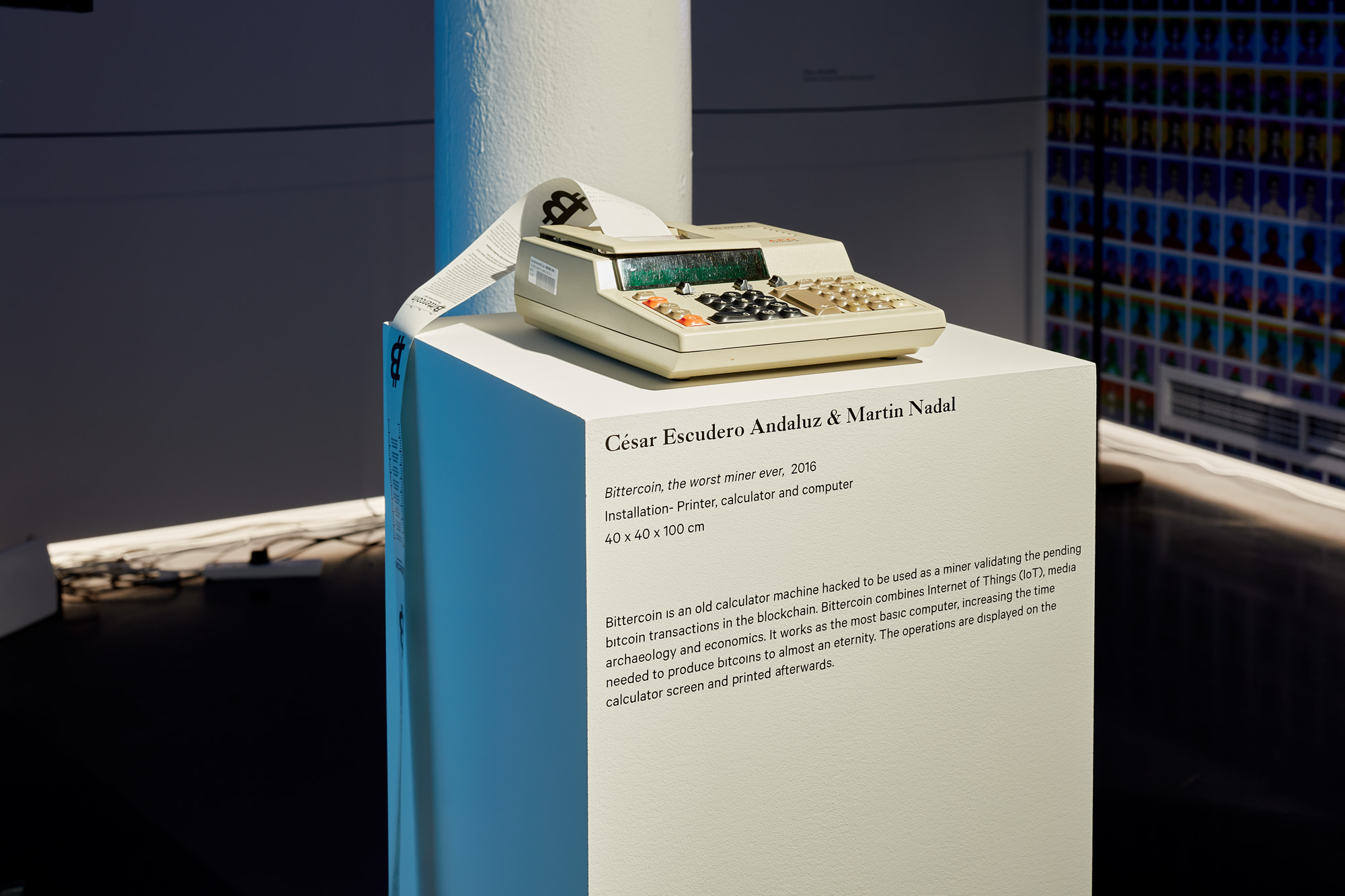

On an unseasonably mild September evening in 2021, I ventured to central London to catch an exhibition opening featuring Bittercoin, The Worst Miner Ever (2016), one of my favorite works of blockchain art.Created by Spanish artists César Escudero Andaluz and Martin Nadal, Bittercoin consists of an old financial calculator (the kind capable of printing its calculations on rolls of receipt paper) hacked to mine for Bitcoin while chronicling its near-futile efforts on endlessly unspooling printouts. The work is part sculpture and part hacktivist experiment, and was conceived as a way for the artists to better understand blockchain technology, while also offering a critique of Bitcoin’s power-intensive proof of work concept and crypto culture’s fixation on wealth accumulation at all cost.

Five years after its creation, Bittercoin was to be included in “NFTism,” a group show curated by Kenny Schachter for Unit London. Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5,000 Days (2021) had been auctioned at Christie’s just a half year earlier, and the NFT hype was still gaining momentum. A commercial gallery exhibition dedicated almost entirely to NFTs still seemed at least a little bit radical. At any rate, I was excited by the prospect of seeing a work as irreverent and roisterous as Bittercoin in a mainstream context. Escudero Andaluz’s critiques are often issued from the margins; now, The Worst Miner Ever was being exhibited in the eye of the hype storm.

Escudero Andaluz’s critiques are often issued from the margins; now, The Worst Miner Ever was being exhibited in the eye of the hype storm.

Bittercoin addresses questions that characterize most collaborations between Escudero Andaluz and Nadal, as well as those made by Escudero Andaluz individually. How does platform capitalism instrumentalize new digital technologies? What ideologies are encoded in blockchain, cryptocurrencies, and their art market spawns? Can artists and everyday users resist assimilation into the circuits of hyper-financialized digital culture that has resulted from these technologies? Escudero Andaluz, who teaches at the University of Art and Design Linz in Austria, has developed intricate strategies for integrating critical pedagogy into his art practice, including DIY instruction manuals, physical computing, participatory performances, and workshops. Nadal, who lives in Berlin and has also worked in art college contexts, pursues similar interests; for example, his project FANGØ, which he began in 2020, is an anti-online surveillance data spoofer that has been shown in several group exhibitions. But while Nadal’s art practice emphasizes software-based art and has focused on wide-ranging topics in the broader critical design domain, Escudero Andaluz’s work features a persistent interest in financial technologies, and a sustained focus on physical computing, DIY aesthetics, andparticipatory formats such as workshops.

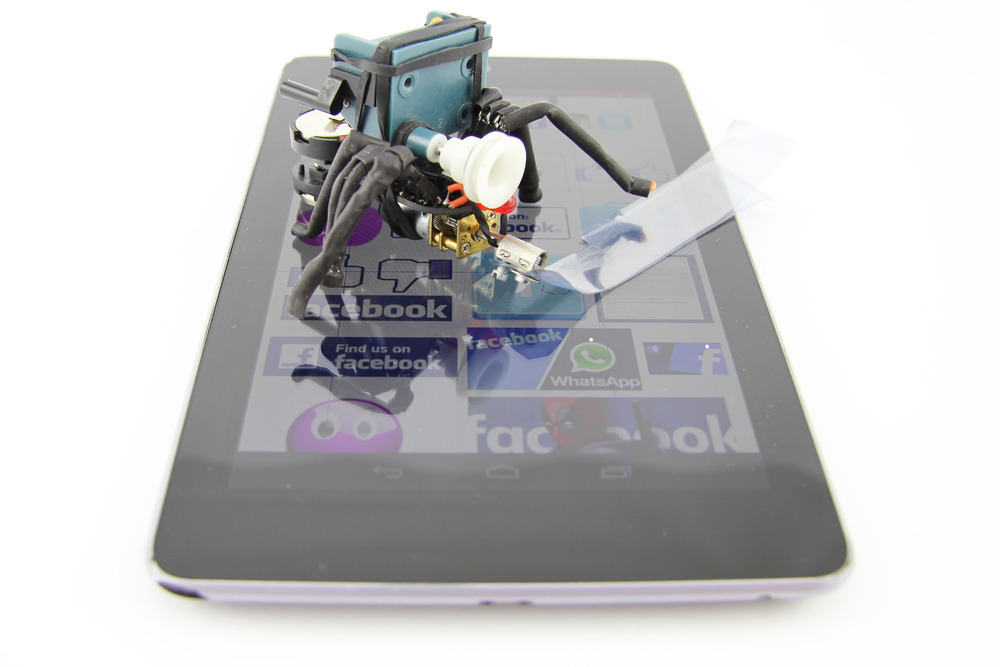

Frequently, Escudero Andaluz’s work explores how artists, activists, and everyday users of technology are subjected to corporate surveillance, data extraction, and labor exploitation. Many of the artist’s projects align with perspectives that invoke copyleft, open-source culture, critical engineering, and hacktivism movements. His treatments of these serious topics tend to be framed playfully, tinged with the wry humor of the tech-savvy tinkerer. Performative elements frequently run alongside didactic components such as manifestos and hands-on DIY guidelines. Inter_fight (2015) and Data Polluters (2016), for example, consist of devices that look like small robotic bugs from a cyberpunk near-future, and which are designed to sabotage the monetization efforts of platforms such as Facebook. Using readily available, often recycled electronic components alongside easily sharable code, the devices feature kinetic elements such a spinning arm that can interact with smartphone screens. In this way, they produce chaotic informational noise that “pollutes” the user data that is commonly scraped when we scroll social media feeds. In a media art context, we can appreciate these bugs as robotic artworks. Additionally, following instructions and DIY kits made available by the artist, we could also easily build these bots ourselves. This is both fun and a good way to learn about counteracting our exposure to surveillance capitalism.

Escudero Andaluz’s treatments of these serious topics tend to be framed playfully, tinged with the wry humor of the tech-savvy tinkerer.

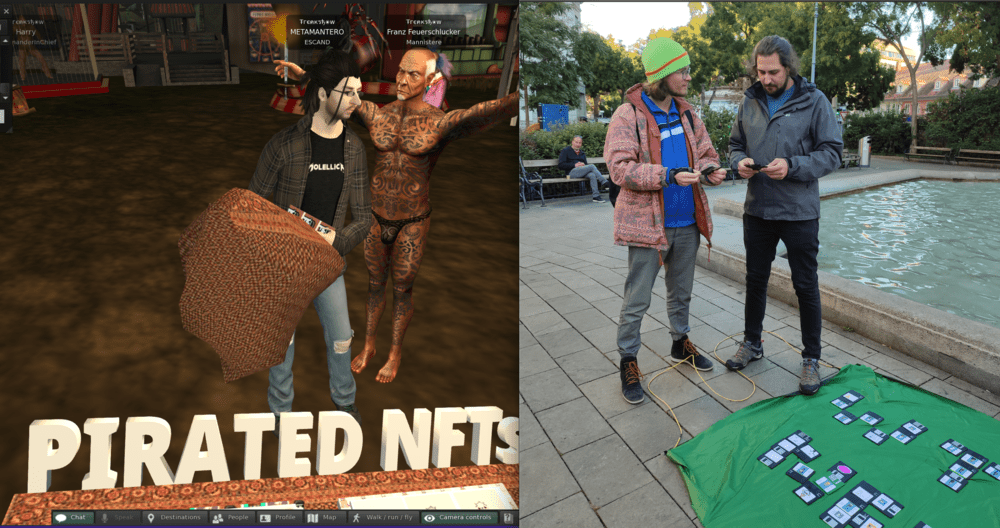

A more recent project, Metamanteros (2022), strikes a similar chord by proposing playful methods for undermining the new forms of corporate control, propertization, and labor exploitation that are emerging in web3 contexts. Specifically, the project critiques the notion of digital scarcity and the enforced use of proprietary platforms for creating, accessing, and sharing creative expression and cultural content. As a starting point, Escudero Andaluz invokes manteros, the road-side hawkers selling counterfeit goods such as fake designer bags and pirated DVDs at the fringes of “developed” world shopping zones. Escudero Andaluz reimagines these vendors as metamanteros: digital avatars who sell pirated NFTs (what else?) in the proto-metaverse of Second Life. While this platform has now mostly fallen out of fashion, it used to be a booming digital economy and has served as an early laboratory both for corporate-controlled, financialized play and for experimental media art. As such, Second Life continues to provide an ideal backdrop for exploring new forms of recalcitrant play through which we can interrogate the web3 world of digital art with critical attitudes.

Like many of Escudero Andaluz’s projects, Metamanteros cuts across different modes of artistic expression. Audiences are provided with detailed instructions for how NFT content can be scraped on the internet and resold on various digital platforms, to reject broad-scale propertization of culture and the assimilation of digital “creatives” into corporate-controlled environments. For Escudero Andaluz, digital technologies should never be separated for the material world; accordingly, he frequently identifies the most effective tactics for resisting globalized tech corporations in materially grounded, local, and community-oriented approaches. Metamanteros, for example, has an IRL counterpart called Guerrilla NFT (also 2022): a workshop template that teaches participants how to encode pirated NFTs on floppy disks, which are then sold, manteros-style, from street-side blankets in a collective performance. As Escudero Andaluz sees it, everyone can—and should—hawk copies of NFTs (whether in Second Life or IRL), and spread awareness of how this technology, which is so often praised for democratizing the art world, can also perpetuate centralized, hierarchical, elitist, and exclusionary attitudes through the financialization of creative practice.

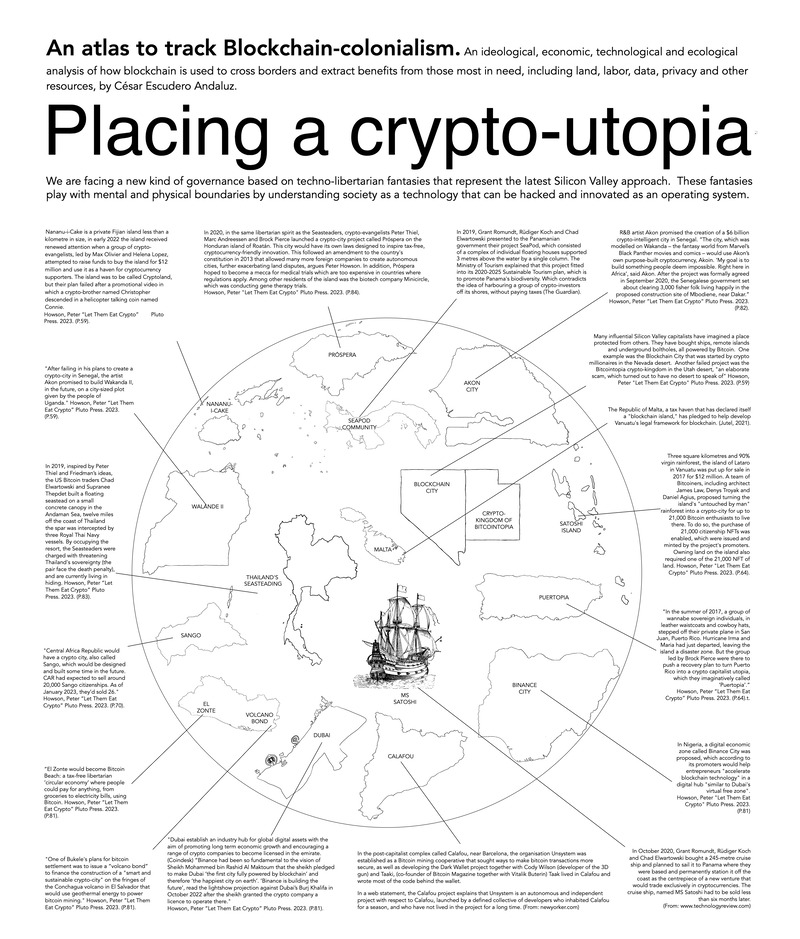

If most of Escudero Andaluz’s work appears to focus on the social and economic imbrications of blockchain and web3, his latest project, An Atlas to Track Blockchain Colonialism (2023–), extends its focus to the environmental impacts of decentralized computing and to the ideological legacies that blockchain invokes. The goal, as the artist recently told me, is to produce a set of maps through which users can trace and interrogate the complex connections between corporate fintech investment, surveillance capitalism, environmental impact, and user-facing applications such as NFT minting tools and marketplaces.

Co-funded by the European Union as part of its ARTeCHÓ program for art, economy, and technology, Atlas continues the artist’s emphasis on creating hybrid formats that combine artworks, critical analysis, commentary, and critical pedagogy. For now, Atlas comprises an in-depth social and historical survey of technology-based colonialism, discussing how radical political and feminist theory can be used to analyze corporate stakes in blockchain tech. To make this survey accessible for non-specialist audiences, Escudero Andaluz has been creating highly detailed diagrams that straddle the genres of infographic, manifesto, and research essay, and which invoke the poetic and speculative traditions of Borges, Calvino, and others interested in the imaginative and critical dimensions of map-making.

But to get back to Bittercoin and its inclusion in “NFTism” a few years ago: given the limited computing power of the old calculator at the heart of what the artists called a “Bitcoin of Things” sculpture, Nadal and Escudero Andaluz have described the likelihood that the sculptural work will ever successfully solve any of Bitcoin’s proof of work puzzles as extremely low. Accordingly, the receipt printouts that pile up around the artwork only serve to document its utter lack of meaningful progress. We can read this as a critical comment on the technology’s carbon footprint more generally. Nadal and Escudero Andaluz have calculated Bittercoin’s resource consumption as amounting to roughly 17.6W of electricity and 10 meters of paper per hour, and its theoretical progress as roughly one hash per ten minutes. Truly, this is the worst miner ever.

Even though the work of this theoretically functional Bitcoin miner appears pointless and wasteful, Bittercoin, because of the ordinary hardware it uses, provides a particularly relatable critique of both proof of work and the hype surrounding blockchain-augmented digital art. Like Bitcoin and like NFTs, a calculator is a quasi-magical invention: it constantly dangles ideas of unfathomable riches right in front of your nose by letting you work with impossibly high numerical values, but it is never likely to make you rich. Ultimately, using a digital calculator, like mining for crypto currencies or trading NFTs, will mostly remind you of the many unfulfilled promises embodied by such technologies.

What was it, I wondered on my way to the Unit London show, that made Bittercoin, with its biting assessment of the world of crypto, resonate for the curator and organizers of “NFTism”? In contrast to most NFTs, the work is sculptural and fully grounded in the material world, and resists the new dematerialization tendencies that characterize so much blockchain art today. Maybe it was just that: if this artwork won’t crunch the right numbers to make you crypto-rich, at least there’s the work itself to hold on to—that’s more than most NFT collectors can claim. The tongue-in-cheek critique of Bittercoin is just oblique enough to appeal to the performative ironic stance of many NFT evangelists.

The tongue-in-cheek critique of Bittercoin is just oblique enough to appeal to the performative ironic stance of many NFT evangelists.

Nadal and Escudero Andaluz couldn’t make it to the exhibition opening, but they set me up with an invitation to the VIP preview. When I arrived at Unit London, I was struck by how empty the gallery was. Where was the art? Where was the open bar? A few small tables were scattered throughout the space, and some monitors and vinyl banners had been hung on the walls. This looked more conceptual than expected! I was intrigued… Soon, however, I realized that I was in the wrong place. On this evening, Unit London’s main location in Mayfair was hosting a social event where hopeful crypto entrepreneurs could elevator-pitch their ideas to invited angel investors. What a fitting mix-up.

I found the real “NFTism” opening at a hip Covent Garden location. There, the scene was very different: a row of people hoping to get in was twisting down the street, kept in line by bouncers sporting earpieces. Inside, a big crowd was drinking signature cocktails as they mingled among flatscreen monitors displaying NFTs in the form of animated and static digital images. Everyone present, I’m sure, agreed with the conclusion drawn in a review in the UK Times a few weeks later: “beats scratching your head over gifs at home.” Bittercoin was set up in a far corner of the gallery, doing its thing on a plinth surrounded by piles of printouts. In the frantic NFT enthusiasm that vibrated through the rest of gallery, Bittercoin felt out of place in the best sense: an artwork designed to provide critical commentary from the margins that had ended up in the thick of it. Like all of Escudero Andaluz’s work, Bittercoin was adding something to the mix that the contemporary digital art world desperately needs: an approach that is open-minded about uses and applications of new technologies, but also uncompromising in its opposition to the lures of art-market trends, and unwavering in its insistence on exposing problematic ideologies inherent in such technologies.

Martin Zeilinger is reader in computational arts and technology at Abertay University in Dundee, Scotland.