Keeping Time

What can a pair of artworks made using clocks teach artists working with blockchains today?

“Technology: Expanding or Erasing the Art World?” This was the title of a talk on the program of Art Basel Conversations at the fair’s current edition. Critic Ben Davis and artist Cecile B. Evans had an animated, wide-ranging discussion that touched on social media, artificial intelligence, and NFTs—phenomena that promise to upset (or are upsetting, or have already upset) the art world’s expectations for things as varied as intellectual property and the mediation of artist-collector relationships. Can a market that thrives on exclusivity and opacity successfully integrate technologies that have brought more openness to so many areas of life? Can art’s slow-moving institutions serve as oases from rapid change, or do they need to catch up?

The risk of staging Digital Art Mile alongside the art world’s most prestigious fair paid off.

Such questions felt especially pertinent this year thanks to the parallel presence of Digital Art Mile, a new fair organized by Art Meta that brought thirteen exhibitors to two venues on a street a short walk from Art Basel. A nearby cinema has hosted a robust program of talks and panels about digital art every day this week. And that programming was supplemented by crossover events where art world stalwarts welcomed their digital counterparts with a sort of anxious enthusiasm. Art Basel CEO Noah Horowitz greeted artists, collectors, and dealers from the NFT space at a cocktail reception Wednesday afternoon by frankly discussing the anxiety and distaste that his clientele of gallerists feels around the new digital art market, and jokingly hoped that the attendees would manage to get away from Digital Art Mile and see “a real art fair.” On Thursday, a grand, airy ballroom overlooking the Rhine was the site of dialogues between digital artists, convened by the platform Taex (which is exhibiting works by Krista Kim at Digital Art Mile) and Jeni Fulton, Art Basel’s head of editorial (who also moderated the conversation about technology’s potential for expansion and erasure). The mood at both events was earnest, as if people were really trying to move past their distrust and learn from each other. The risk of staging Digital Art Mile alongside the art world’s most prestigious fair paid off.

It’s no secret that the art market is going through a rough patch, and exhibitors at Art Basel are playing it safe, hanging booths that aim for surefire sales rather than curatorial excellence. But at Digital Art Mile exhibitors are taking the chance to show off. The standout is Fellowship, an organization that started out using the blockchain to license and sell photography archives (as described in a 2022 article for Outland), but has since shifted focus to contemporary work made with artificial intelligence. At Digital Art Mile they’ve staged a thoroughly researched and elegantly presented exhibition of milestones in AI art. It includes experiments from 2015 by machine vision researchers Alexander Mordvintsev and Elman Mansimov that weren’t intended to be art, as well as recent moving image works, such as Rachel Maclean’s DUCK (2023), where the artist uses deep fakes to appear as iterations of James Bond and Marilyn Monroe. The show features the outcomes of both well-funded research and DIY engineering, reminding us that these practices are in dialogue with one another, not poles on a binary. This perspective offers a corrective to the “expanding or erasing” question; it shows how artists working within or alongside disruptive technologies find space for reflection. Fellowship has made these works available as editioned prints and unique NFTs—an inversion of the standard relationship of digital and physical versions that privileges the origins of born-digital art.

“Collaborations with the Artificial Self” occupies the whole ground floor of a sleek art space, while the bulk of the exhibitors are on the fourth floor of a renovated warehouse. Even though the digs aren’t as nice, there are still some ambitious presentations. Paris-based RCM Galerie, a specialist in twentieth-century computer art, offers a few dozen works on paper with plenty of surprises for those who think that era is defined by repetitive patterns of rectilinear shapes. Ken Knowlton’s Birds (1967) assembles a pair of in-flight silhouettes from emoji-like glyphs—schematic trees, animals, and faces. Barbara Nessim’s untitled 1981 computer drawing with a watercolor finish juxtaposes a woman bathed in pastel tones and a figure sketched in energetic black lines, at once cartoonish and haunting.

Makersplace, a curated online platform, is presenting three very different approaches to art with code. Juan Rodríguez García applies generative procedures to models of the human body to make colorful multifigure compositions. Eko33 codes his own ways of interfacing GANs and hand-coded algorithms, marrying different approaches to image generation to produce ragged, wavering lines that are rendered by pen plotter. An installation by Operator includes a print of an output the artists kept from their generative choreography project Human Unreadable (2022), as well as a deck of cards for producing random sequences of that project’s movement by analogue means. Makersplace stands opposite the big booth of fxhash, which selected a handful of the artists who mint work on its open marketplace and who represent the platform’s tendency toward minimal geometric abstraction. While most of the works here were digital, there were some physical outputs as well, notably Andreas Rau’s Klangteppich (2023), with rugs he wove by hand on a loom from images that visualize generative sound.

The only other digital art fair of this caliber is Art Dubai Digital, which I got to see in its second and third editions, and comparing the two yields some productive insights. Both piggyback on traditional art fairs, but Digital Art Mile is an independent venture, whereas Art Dubai Digital is a section of Art Dubai. This influences how they’re perceived. Art Dubai Digital ends up getting associated with the category of “special programming” along with performances that aren’t expected to sell. As a viewer I appreciate that open-endedness, but the exhibitors I spoke to who participate in both said they prefer Digital Art Mile, where visitors intuitively understand that the dealers are there to sell and thus take them more seriously.

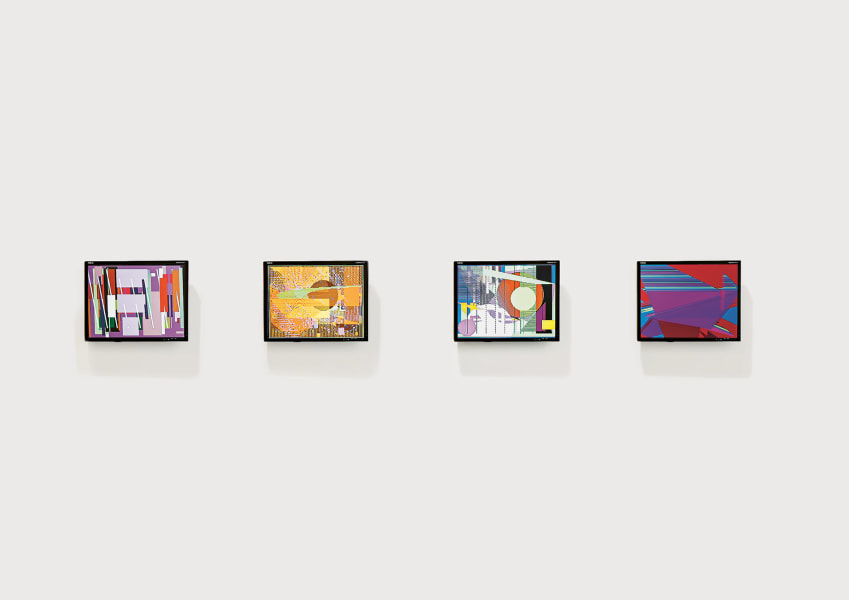

Art Basel, of course, has its own special programming where digital art makes occasional appearances. Unlimited, a section for work that is for sale but whose scale exceeds the standard booth, featured a presentation by Sfeir-Semler Gallery of the work of Samia Halaby, an abstract painter who got a Commodore Amiga in the mid-1980s and tested its image-making capabilities. Before Photoshop and its ilk offered skeumorphic tools to imitate the textures of oils and acrylics, Halaby programmed animated sequences in a 64-color palette. She didn’t translate painting to software or vice versa, but developed a language of lines and planes that could be articulated in both mediums. This is apparent in the display, which hangs a large painting kitty-corner to a series of monitors playing her kinetic digital works.

Digital art also appears among the sponsored booths in Unlimited’s lobby. Flight attendants from Turkish Airways invite passersby to enter an installation by Refik Anadol. On the screens inside, portraits of people melt into bands of tiny spheres that twist and flow in the signature moves of Anadol’s AI-powered CGI, which here supposedly visualize his subjects’ brainwaves as they fantasize about travel. Anadol’s prominence in recent years means that this kind of immersive spectacle is what many people expect digital art to look like—so it’s good that Halaby, and of course Digital Art Mile, are around to represent other approaches and traditions.

Next to the Turkish Airways booth, Samsung is presenting The Frame: digital TVs with handsome casings that display a rotating set of images when not in use. The sample imagery includes reproductions of modernist paintings and anonymous, anodyne pictures of animals and landscapes. This felt like a missed opportunity to curate a show of emerging digital artists. Or would that have made Art Basel’s exhibitors nervous? “As we redefine the art experience, we recognize and honor the contributions of existing galleries,” says Samsung’s obsequious wall text. “We truly appreciate the joy these galleries bring us.” The fear of erasure continues to block expansion.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.