Economic Provenance and the Audit Problem

How can expertise from time-based media art conservation help appraisers vet NFTs?

“The security guards looked pretty nervous,” Chidirim Nwaubani told me with a chuckle. He’d just arrived back at his studio in East London from the British Museum, where he and a colleague had been on something of a Saturday-morning mission. Their goal? Nothing less than the repatriation of the Benin Bronzes. But unlike the perpetrators of other high-profile examples of decolonial activism in museums, who have incurred court summons and fines, Nwaubani walked off scot-free. He had taken from the museum not artifacts but merely photographs.

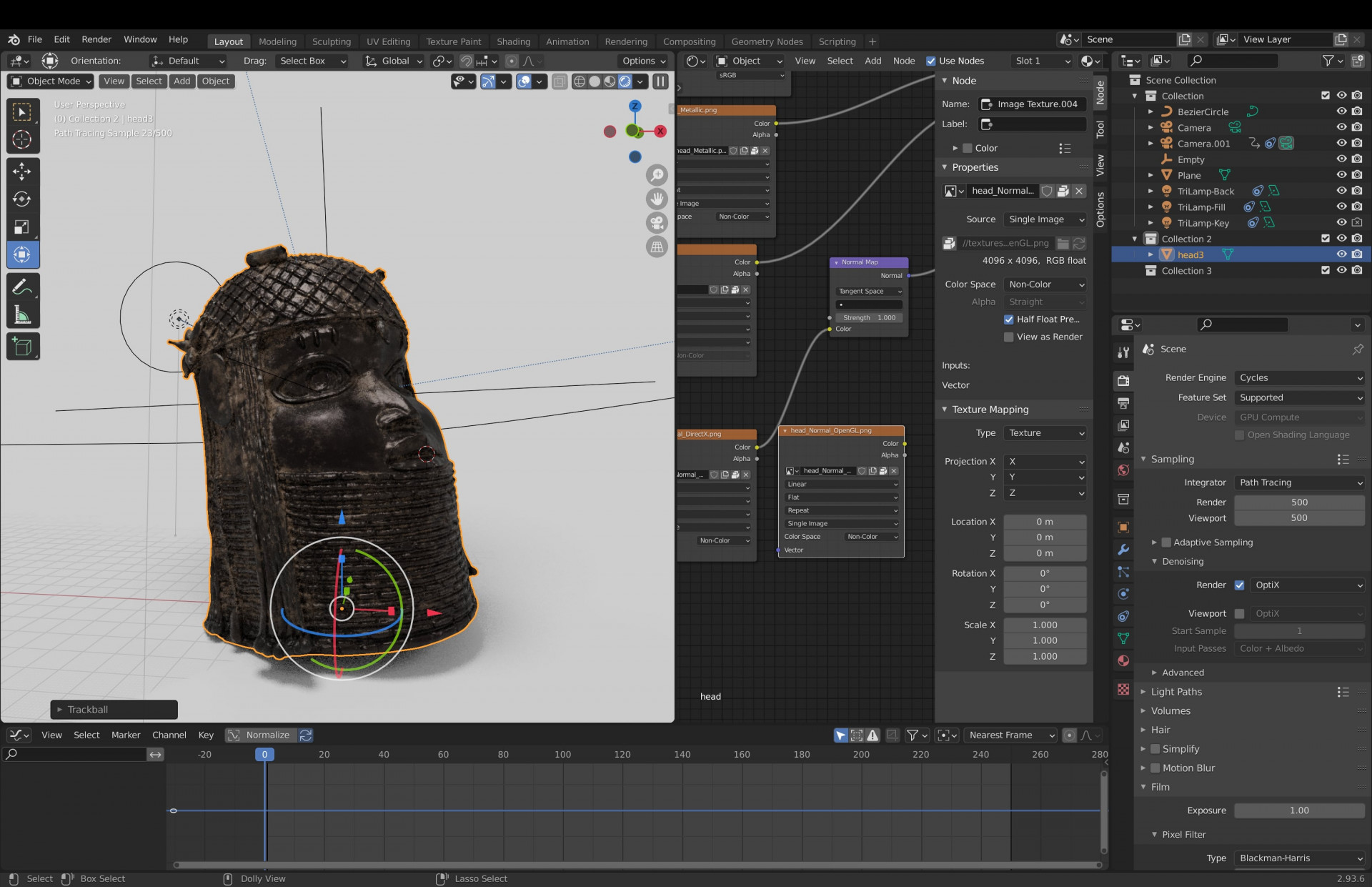

Nwaubani runs an NFT platform called Looty—named, with tongue firmly in cheek, after Queen Victoria’s prize Pekingese dog, which in turn took its name from the method of its acquisition, a raid of the Summer Palace in Beijing in 1860. The latter-day Looty’s inaugural collection of Benin Bronze NFTs are modelled from 3D digital scans of one of the famous cast-metal sculptures looted by British soldiers from the Kingdom of Benin, in what is now southwestern Nigeria, that have come to symbolize the broader debate around the restitution of cultural heritage taken during the colonial era. The collection dropped in June: an inauspicious time, Nwaubani admits, though he told me that he has taken the dive in the NFT market as an opportunity to regroup, and focus on building the relationships and networks that will underpin his more ambitious hopes for the project. “If you look at the time when a lot of these artefacts were taken,” Nwaubani said, “the Industrial Revolution had given the Western world a clean slate, and it managed to capitalize. Web3 offers another clean slate—and this time, we need to take control of the narrative.”

Are NFTs just another tool to galvanize the demands for restitution, or might they represent a more fundamental shift to the terms of the debate?

In the context of growing calls for the return of objects taken during the colonial era, it remains to be seen what precise role NFTs and web3 might play: are they just another tool to galvanize the demands for restitution, or might they represent a more fundamental shift to the terms of the debate? For Looty, it is very much the latter—the main goal of the project is a metaverse museum, which it hopes to launch this time next year. The planned museum will be accessible to the public through AR and VR and will house a collection of historical artifacts from the African continent (after the Bronzes, Looty has set its sights set on the Rosetta Stone). There will also be new commissions by contemporary African artists on display to “reimagine” the older pieces, while 20 percent of proceeds from the sale of NFTs have been earmarked for grants to be awarded to young African “creatives” through the Looty Fund. The idea is to bridge not only past and present but also East and West Africa; partnerships have been struck with a museum in Rwanda and with Yinka Shonibare’s Guest Artist Space foundation near Lagos, where Nwaubani recently staged an exhibition with Nigerian artist and fellow blockchain advocate Femi Johnson. “It’s about rewriting what we believe a museum to be,” Nwaubani said.

While Looty describes itself as “the world’s first digital repatriation of art to the metaverse,” in fact the term “digital repatriation” far predates the rise of web3. It emerged among anthropological circles in the early 2000s as a means of describing how tangible artifacts taken from their original communities during the colonial era and housed in Western museums might be meaningfully substituted by digital “surrogates”: images, videos, sound recordings and other forms of digital (or digitized) archival material. Anthropologists involved with digital repatriation have often been at pains to point out that these surrogates are not intended to function as replacements for physical objects—they have different uses, sometimes serving as supplementary context for these materials, and sometimes as stand-alone resources giving access to forms of intangible cultural heritage (songs, for instance). But that has never quite allayed fears among some Indigenous leaders of being fobbed off: a suspicion that was memorably expressed by Jim Enote, a Zuni tribal leader and director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center in New Mexico, before a congregation of anthropologists at the Smithsonian Institution in 2012. “If the digital is so good, why don’t you keep it?”

Looty is not the first project seeking to harness NFTs in the push for restitution—though it is perhaps unique in focusing its efforts solely on returns in the digital sphere. Last November, Bronze DAO launched, with the aim of “utilizing web3 technology” to raise funds and, ultimately, buy back some actual Benin Bronzes (although the organization hasn’t been particularly active since then). Then in February came perhaps the most high-profile entry into the fray to date, emerging from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For two years prior, the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC)—a collective that in 2017 co-founded White Cube, a contemporary gallery in the middle of a palm oil plantation outside Lusanga—had been attempting to obtain on loan a carving currently held in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The carving depicts Maximilien Balot, a Belgian colonial officer beheaded during the Pende uprising of 1931, in retaliation for his officers’ rape of Pende women at the same plantation where White Cube now stands; Pende tradition holds that carved effigies encaged the vengeful spirits of defeated foes. With the museum unwilling to cooperate, two artists with the CATPC—Ced’art Tamasala and Matthieu Kasiama—decided to take matters into their own hands. They minted an NFT of the sculpture, with 306 unique copies later going on sale for 0.2 ETH each—then equivalent to the price of a hectare of land in Lusanga, which they intend to buy back from multinationals with the proceeds.

The Balot NFT gained widespread media attention, not least because of the reaction of the museum, which escalated tensions by accusing the CATPC of copyright infringement. The museum claims its photograph of the sculpture was used without consent; Renzo Martens, the Dutch artist who collaborated with CATPC on White Cube in Lusanga, counters that the NFT falls under fair use. And it’s clear that the publicity generated by the Balot NFT, which went on show at Art Basel this summer and has since been touring venues in Africa, is largely the point. When I spoke to Ced’art Tamasala, he was skeptical about the idea that NFTs, divorced from their referents in the real world, can constitute meaningful return. The digital copy can go some way to “recovering the force of the sculpture,” he said, “for the benefit of the inhabitants of Lusanga … where our ancestors suffered forced labour in the imposed monoculture.” But Tamasala also believes “there is indeed a difference between the NFT and the physical sculpture.” The primary goal remains the return of the latter to Lusanga. He is also concerned about the environmental impact of NFTs—unsurprisingly, given that his organization was founded with the mission to achieve the equitable distribution and proper use of plantation land. “We’re going to plant a variety of trees to compensate,” Tamasala told me.

Physical acts of restitution are “too little, too late,” since the meaning of the objects has been irrevocably changed during their confinement in the West.

Echoing Tamasala, Nwaubani suggests that NFTs can be a means of replicating the force or “the aura” of a historical work, but in most other respects their views are poles apart. Nwaubani feels that he is building on the anthropological definition of “digital repatriation”—and yet he goes somewhat further, in proposing that NFTs can function as digital surrogates that do, ultimately, replace the physical object. Physical acts of restitution are “too little, too late,” since the meaning of the objects has been irrevocably changed during their confinement in the West. “It’s like abducting a child, and returning it as a pensioner,” as he put it. And he noted with indignation a section of the 2018 Sarr-Savoy report on restitution in France, which recommended open-access digitization of African cultural heritage. This recommendation has been widely called into question: Should it not be African institutions making the decisions over who has control of digital resources? “I think they’re aware of the same thing that we’re aware of—that there’s a time in the future when the digital will replace the physical,” Nwaubani said.

There are many in the museum world, having built their careers around physical objects, who are unlikely to be converted to such a notion any time soon. But it seems fair to say that when Jim Enote posited his question about the value of digital artifacts ten years ago, it was hard to imagine a world where those terms could be so easily flipped.

Samuel Reilly is assistant editor of Apollo.