Commentary

Financialized Play on the Blockchain

by Martin ZeilingerMore and more, video games look like capitalism simulators and digital financial products look like games. Can art offer an alternative?

Let’s imagine the premise for a simple game—something a bit like charades, but with a twist. In this game, you draw a prompt and then describe it to the other players, trying to make it as easy as possible for them to guess it correctly. There are two types of prompts. One contains the title of a video game (say, 2016’s Stardew Valley), while the other shows the name of a digital finance product (such as Revolut). Our hypothetical game features an important constraint: when responding to a video game prompt, you’re limited to terminology related to the world of finance, whereas any prompt showing a digital finance product must be described using only game-related language. For Stardew Valley, this could mean describing the game’s mechanics, social interactions, farming activities, and quests in terms of investment choices, resource management, wealth accumulation, and transactional exchanges. For the online banking service Revolut, it could mean describing the app’s financial functions, including its online banking features and the many ways in which it incentivizes you to use transfer, payment, and savings functions, only in terms of game rules, goals, rewards, win states, narrative cues, or environmental storytelling devices.

I am willing to bet a big stash of coins and powerups that this little imagined game would work perfectly. Why? Because more and more video games are designed to take the form of complex capitalism simulators, whereas more and more digital finance products are designed to be experienced as if they were games. Consequently, terminological and conceptual distinctions between games and finance are becoming difficult to maintain. What is the language of finance today? What is the language of games? The lines between play and financial activities have become exceedingly blurry. Our reimagined version of charades explores the extent to which the realms of finance and games now share conceptual horizons. But what are the critical implications of this convergence—this simultaneous financialization of play and gamification of finance? NFT art projects, I think, provide some of the best context for reflecting on this development.

What made the NFT boom that crested in 2022 such a fascinating phenomenon was the technology’s perfect suitability for exploring resonances between finance and play. Today, a quick web search will yield hundreds if not thousands of mainstream NFT projects in which tradeable digital assets are designed to invoke video-game aesthetics, in which the financial transactions required to participate are dressed up as playful interactions, and in which engagement is incentivized through the promise of manifold rewards. Think, for example, of the pixel art aesthetics of the CryptoPunks, or of the blockchain-enabled, NFT-driven in-game economy of Axie Infinity’s online sandbox. In more experimental and conceptual contexts, digital artists have also been fascinated by the many ways in which blockchain tech allows for interactions that can invoke play while simulating (or sometimes subverting) the operational logic of financial technologies. Critically acclaimed projects such as Jonas Lund’s JLT (2018–) or Sarah Friend’s Off (2021–), for example, are strongly informed by thinking about connections between games and economics. JLT casts the artist’s entire career as a tokenized, participatory series of events in which Lund has committed to playing along with the choices his profit-sharing stakeholder community makes regarding what art to produce, where to show it, or how much to sell it for. Off, by contrast, is an NFT series of rectangular black images that also function as a multiplayer game. Here, owners can collaborate on finding ways to decode the invisible content of the images.

We can talk about the critical appropriation of fintech and defi in post-digital aesthetics all day, but there are also highly problematic moral ambiguities at play here.

A key question raised by such projects concerns the responsibilities of digital artists when designing new aesthetic experiences that combine gamification and financialization. In a generous reading, blockchain-enabled, transactional digital art can be described as providing commentary on the intersections between creative practice, play, and capital. (In fact, many artist statements and curatorial essays on blockchain-enabled art do just that.) But much of this art could just as easily be accused of complicity in the financialization and gamification efforts of informational, platformized capitalism. I would venture that this is true also for some community-focused DAOs that incentivize participation, engagement, and speculation, even when they have laudable goals such as climate action, fair wealth distribution, decolonization, or social justice. Yes, we can talk about the critical appropriation of fintech and defi in post-digital aesthetics all day, but there are also highly problematic moral ambiguities at play here.

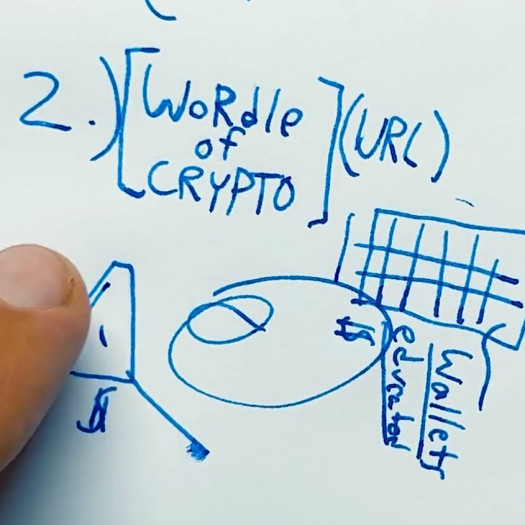

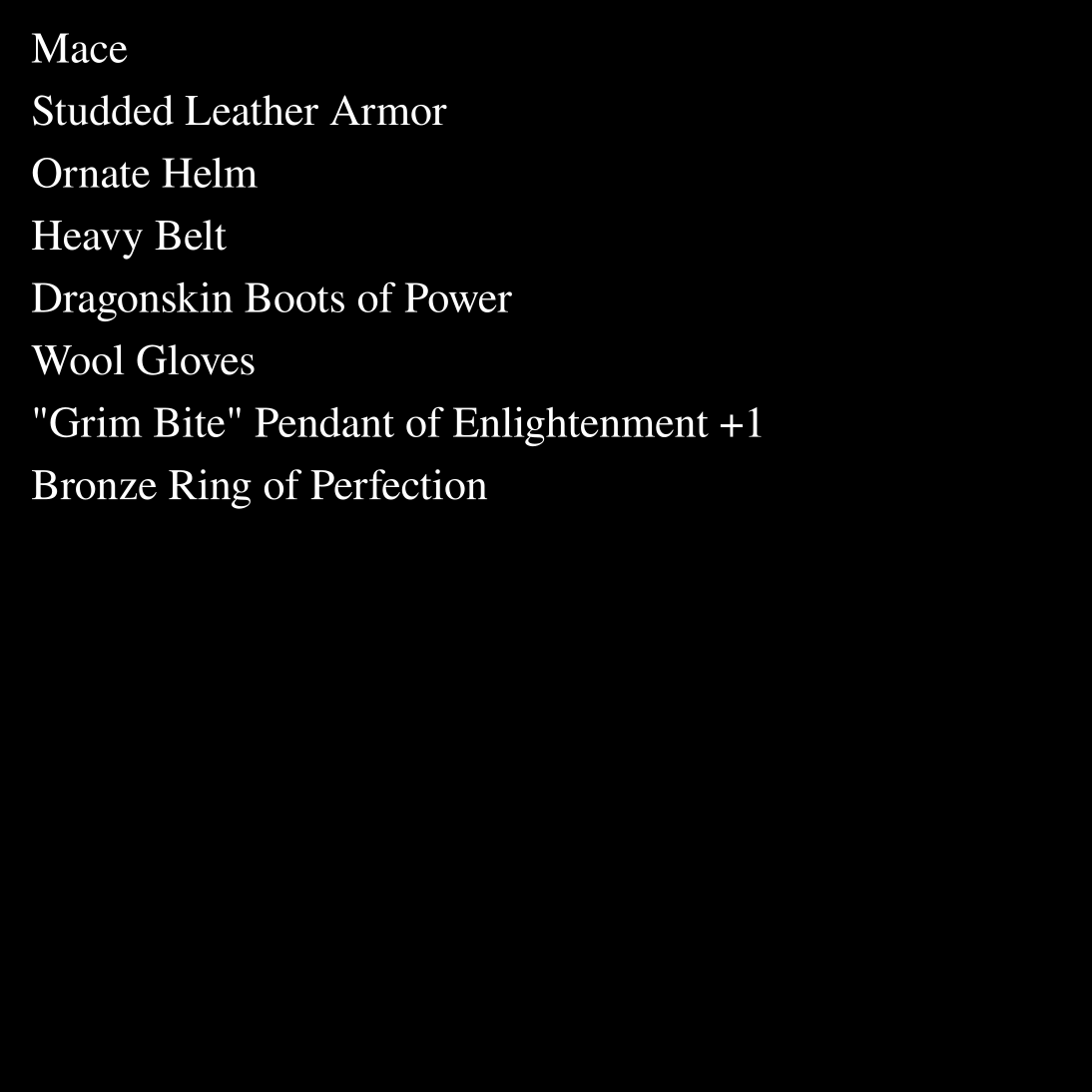

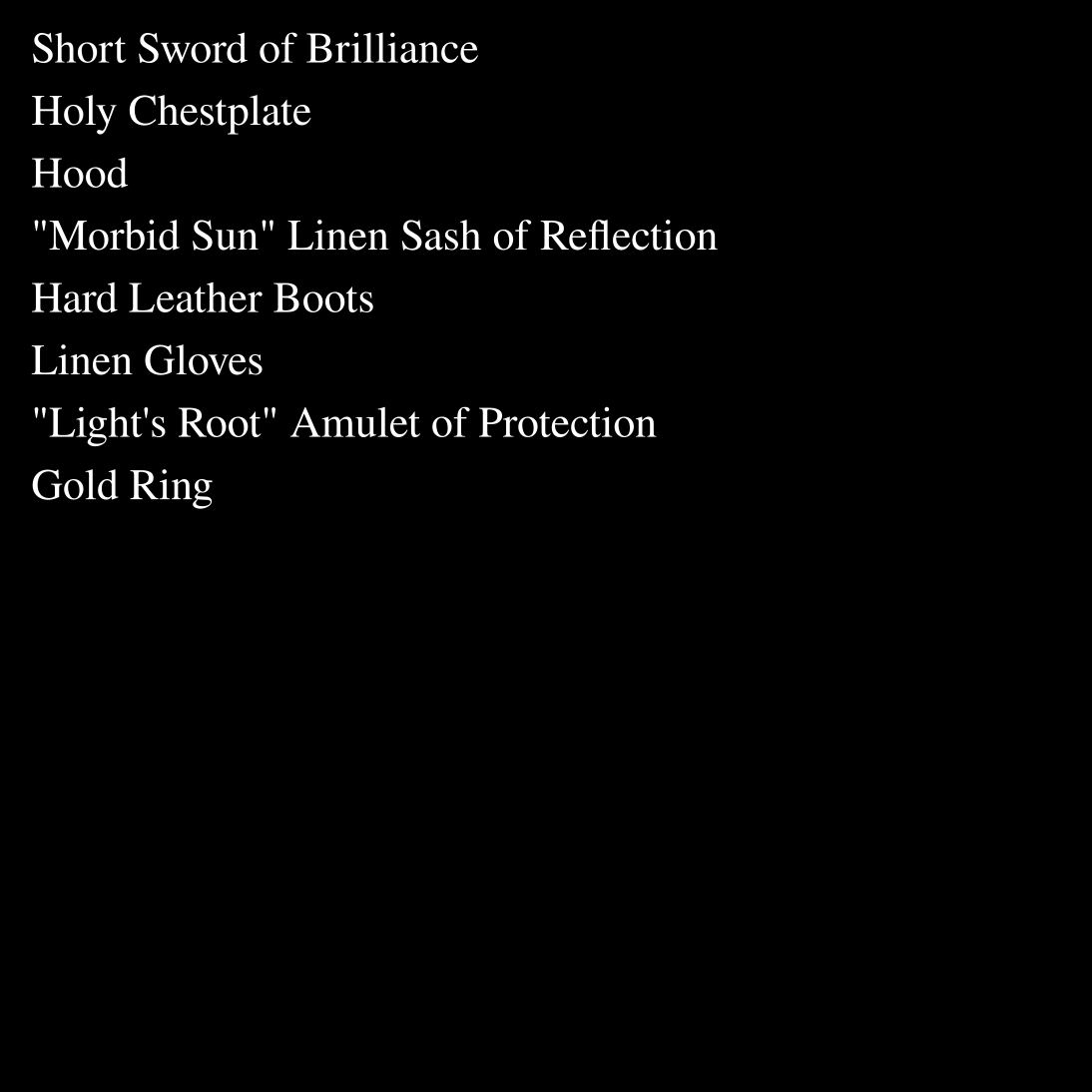

At its most extreme, the convergence of monetization and play takes the form of what Kevin Buist, in a widely noted 2021 essay for Outland, has usefully described as “ectogames:” “NFT projects that offer elements of games—characters, gear, fictional settings, lore, strategy, and even player communities—but lack the organizing form of a game.” The experience of interacting with ectogames such as Dom Hofmann’s Loot (for Adventurers), which was released in late August 2021, will almost certainly have a playful quality for most users. And yet, this is not a game in any conventional sense of the term. In an ectogame, rules are deliberately vague or entirely absent, and there’s usually no clear definition of what it might mean to win or lose. Often, it is up to players themselves to bond together and give meaning to their experience. This tends to happen in social interactions that take place entirely outside the project, for example when users write lore, add visual content, or make up rules to help shape the outcome of their involvement. Loot set a high bar for this kind of design. The project was framed around eight thousand generative, text-based NFT collectibles featuring descriptions of the kinds of fantasy equipment, armor, and weaponry contained in the “loot bags” familiar from role-playing video games. However, the itemized lists of the Loot NFTs offered no hints for what could actually be done with the asset tokens. No matter: all available tokens were minted within three hours, and a week later, the project’s daily OpenSea trading volume exceeded 100 million USD. Within days, derivative projects representing monetized forms of user-generated Loot lore began to appear, with astronomical combined market caps.

Yet this success story tells us nothing about what makes the experience of engaging with Loot game-like. Buist insists that ectogames “are not gamification.” This is correct, as I understand the concept, to the extent that his term applies to the individual assets (artworks) contained in the collection, and to the whole that they represent in the fuzzy relationships among them, as defined by the artist and perceived by collectors. In this sense, ectogame is an aesthetic category that activates the imagination and inspires playful interaction in ways that are evocative of (but not identical to) games, and without having to rely directly on the reward cycles of gamification techniques. But that’s never all there is to it. Inevitably, ectogames always also emphasize the dynamic of competitive collectability by which NFT technology’s underlying market logic of tokenization is fundamentally characterized.

In the financialized play that is required to participate in ectogames, making any move always has the potential to be both fun and profitable.

Is it fair to say, then, that even though ectogames themselves might not entail gamification techniques, they also don’t work without them? In the absence of discernible game structures (such as rules, a narrative teleology, winnable quests, etc.), incentive for engagement and participation appears to be mainly provided through the ambient noise of trad blockchain rhetoric and the elusive financial promises linked to trading project tokens or creating new monetization contexts for them. This is true for Loot, and it also applies, I think, to other projects that fit into the ectogame category. Pak’s celebrated Lost Poets (2021–), for example, is a very artfully presented NFT collection released in multiple stages that can be described as a strategy game without rules, as a sophisticated set of playful literary references (to Jorge Luis Borges’s famous short story The Library of Babel), and as a generative poetry experiment. All of these descriptions are spot on, but they are also incomplete, since they fail to account for the project’s most fundamental aspect, namely its intricate, ornate incentivization of users to participate in asset collection, complex transactions, and value-generating content-creation. Writing on Lost Poets in Outland, A.V. Marraccini argues that the project improves on historical models for the design of participatory conceptual art projects, because the significant financial stakes for involvement and the elusive promise of potential profits help increase and sustain user engagement. This is correct, of course. But it is also a case in point regarding my observation that ectogames, by way of financialization, certainly dorely on gamification techniques.

If NFT projects such as Loot and Lost Poets are not games in the conventional sense, and if they are not, as Buist argues, gamification, then what are they? As noted earlier, the current definition of the ectogame does not quite seem to capture everything that is going on here. Instead of trying to identify such projects as new types of game-like non-game objects, it might be more useful to think about the behaviors these media artefacts inspire. With regard to the examples of Loot and Lost Poets, user behavior registers as “investment” in a double sense of the word—both in terms of the financially motivated activities of collectors and in terms of the sustained attention they devote to the projects’ playful aesthetic, artistic, and pseudo-narrative appeal. In my view, this combination represents a new modality of financialized play. In this type of play, different value systems are conflated and muddled together. Here, it doesn’t matter whether we’re dealing with a recognizable game structure, narrative, or rules, because there’s always also the option of profit-based “winning.” The behaviors inspired by Loot and Lost Poets bear all the hallmarks of financialized play, including its reliance on the gamification techniques characteristic of mainstream blockchain culture. Beyond the game-like and quasi-narrative layers, in such ectogames you’ll quickly find token-gated access to participatory elements; leaderboards on owner-exclusive social media channels; privileged access to interactive elements that only become available through trading activities; and promotional rhetoric that masks the degree to which participating in the projects resembles gambling.

In the financialized play that is required to participate in ectogames, making any move always has the potential to be both fun and profitable. The risks involved will give players an existential thrill both within the “magic circle” of these not-quite-games and in their functioning as fintech vehicles. This is a highly complex scenario, and it’s easy to lose track of what’s what. The resulting uncertainty can be exhilarating but also dangerous—in ways that are both playful and very real. As the lines between play and financial activities are becoming more and more blurred, we have to think harder about how the effects of platform-based gamification change the social, cultural, and psychological meanings of play, how our definitions of games change when they are being financialized, and how gamification impacts our attitudes to money. In this emergent scenario, digital artists should recognize a responsibility to reveal and critique the insidious convergences at play here, rather than finding ways to blend in.

Martin Zeilinger is senior lecturer in computational arts and technology at Abertay University in Dundee, Scotland.