How to Glitch AI

Prompt-based image generators seem unhackable. But a committed glitch artist can still instigate interventions.

On February 27, I spotted a tweet by the anonymous artist Pak that began, “As a creator, politics bores me. I ignore it. So none of my moves are political…” The tweet was widely mocked and later deleted, but it spoke to a broader issue that I’ve noticed as NFT creators gain visibility. Many of them want financial and cultural power but they seem keen to avoid political power, even though those three pillars converge as they rise. Artists making NFTs are political actors whether they aim to be or not. They’re either propagandists for the ideological assumptions embedded in the technology they use, or they’re peeling back the layers to reveal the political assumptions behind the images, protocols, and conceptions of value inherent in NFTs. Artists, NFT or otherwise, don’t have the luxury of opting out of the political implications of their work.

Ethereum’s creator Vitalik Buterin is quoted in a recent Time profile lamenting that the blockchain he developed may be evolving to serve financial and political interests that go against his egalitarian sensibilities. “One of the decisions I made in 2022 is to try to be more risk-taking and less neutral,” Buterin says. “I would rather Ethereum offend some people than turn into something that stands for nothing.” This is admirable on Buterin’s part, but like Pak’s tweet, this quote reveals a flawed assumption. Regardless of what Buterin does now, it’s not possible for Ethereum to stand for nothing. Ethereum was built to extend the anonymous, trustless, libertarian ethic of Bitcoin beyond stateless currency and into more complex contracts that can authenticate off-chain goods, automate governance, and run executable programs. Buterin did not build Ethereum as a neutral platform. His politics are built into the protocol. The Time profile is fascinating because it depicts a concerned Dr. Frankenstein realizing the power of his monster long after it has escaped the lab.

Many NFT artists want financial and cultural power but they seem keen to avoid political power, even though those three pillars converge as they rise.

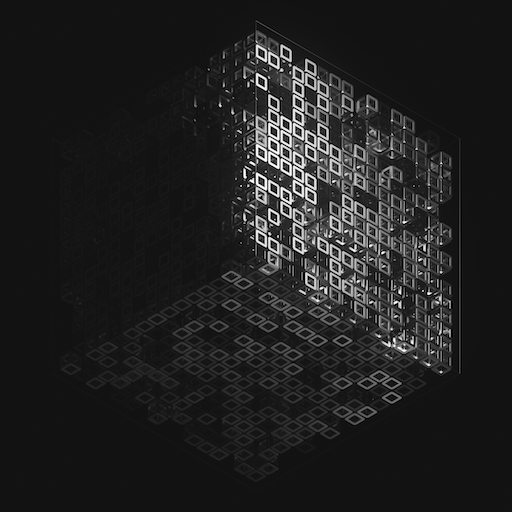

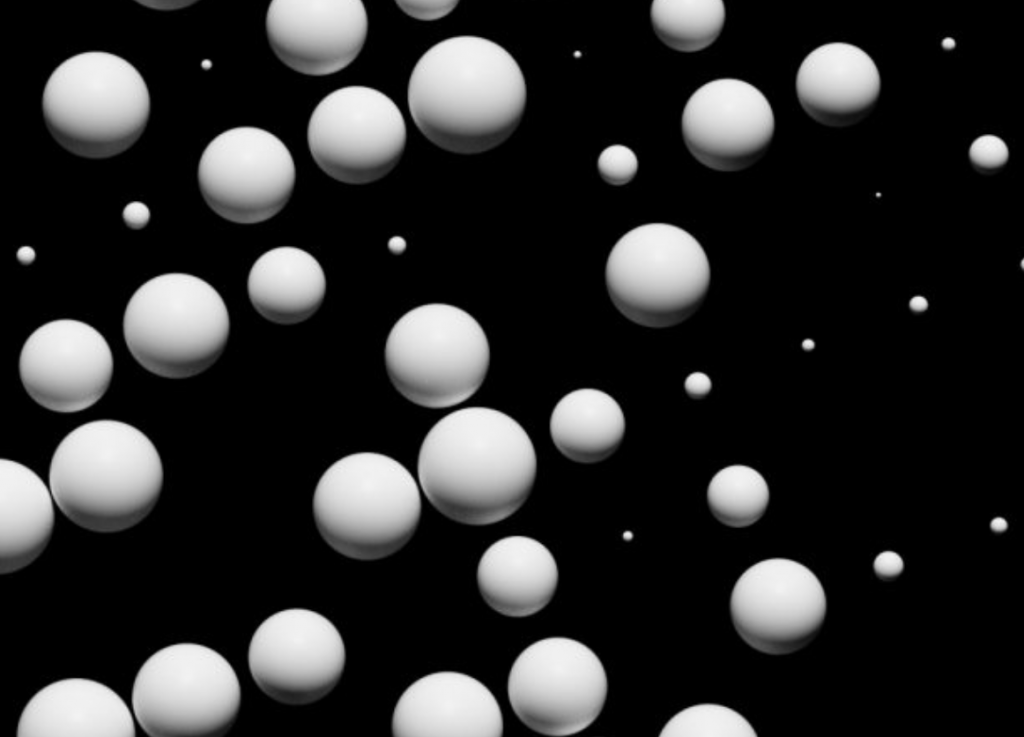

Pak is far from the only artist in the space eschewing their relationship to politics, but their retreat from this reading is particularly surprising given the way their work manipulates the core assumptions of the blockchain itself. Pak is known for making minimal and conceptually intriguing projects that offer fresh proposals for what NFTs can be and how they hold value. “The Fungible” was a partnership with Sotheby’s and Nifty Gateway that netted 16.8 million USD over three days in April 2021 by selling a series of NFTs, mostly images of cubes, in open editions, auctions, and reserved sales. Collectors were awarded additional prizes for acquiring large quantities of cubes, solving puzzles, and estimating the auction’s sales volume. In December, Pak released “Merge,” a 48-hour sale where 312,686 “mass units” sold to 28,983 buyers for a total of 91.8 million USD. (Disclosure: I bought one.) These are simple images of dots. If a crypto wallet acquires more than one, they merge into a single NFT, the dot growing proportionately larger. As collectors compete to get the biggest dot, the total number of NFTs in the collection decreases.

Through the experimental sales models of “The Fungible” and “Merge,” Pak approaches the fundamental qualities of blockchain technology—immutability, rarity, value exchange—as materials to be manipulated. By playing with the unspoken tendencies and limitations of NFTs, Pak is making visible the conditions in which all crypto artists operate. While many see NFTs as inconsequential deeds of ownership loosely tied to digital illustrations, Pak makes the blockchain both the medium and the subject of the work. They create work that digs into the financial implications at the core of blockchain technology, opening them up to examination and critique. Or at least that’s what I thought.

The “politics bores me” tweet was part of a thread announcing that Pak had given 670 ETH (1.8 million USD) to the government of Ukraine to help defend against the Russian invasion. It was a generous donation, to be sure, but this money may have a strange connection to the aggressor in the conflict. The 670 ETH was earned as part of a project Pak did just a few weeks earlier called “Censored,” which raised money to help Julian Assange fight his extradition to the United States. All told, “Censored” raised far more than the donation to Ukraine, 17,422 ETH (nearly 55 million USD), while the 670 ETH was Pak’s take for an open edition of NFTs that allowed buyers to input text that was crossed out by a thick line to create NFTs. Pak’s attempt to opt out of politics was not only naive, it also obscured that Assange was at least the Kremlin’s tool, if not ally, when he leaked documents to damage Hillary Clinton while declining to publish incriminating information about Vladimir Putin.

Pak’s tweet declaring their ignorance of politics, written amid highly political collaborations and donations, began an unexpected exchange between the artist and me. In response to the tweet I commented, “The thing about politics is that if you think you’re above it, it just means that you’re so enmeshed that you can’t recognize it.” Pak sent me a direct message shortly after that (we had never been in touch before). They clarified that the tweet was part of a thread about the donation to Ukraine, and suggested that I was misunderstanding the intent. I responded that artists make things that have consequences, and some of those are political. Collaborating with and providing financial assistance to Assange was indeed a political act.

Pak replied by saying that they don’t follow US politics and that the Assange project was supposed to be about censorship. They lamented that their support for human rights and freedom was being “read politically” by others. As our DM exchange continued, I pointed out that the design of the blockchain is inherently political. It’s a transnational system for value exchange that evades taxes and rewrites protocols of ownership. These political entanglements aren’t necessarily a bad thing, but they’re a reality that artists must contend with. I used examples of some of Pak’s own works, like “Merge,” to illustrate how artists can successfully manipulate the dynamics inherent in the technologies they use.

Pak’s response to my attempt at a compliment was evasive. They sent a link to a tweet of theirs from last September which simply states, “I am not an artist.” They then added:

I am very strict about my self definition. Designer.

If people want to read my creations as “art”, good for them. So, while I can’t comment on how art interacts with politics, I can comment for design.

Tell me how a cube I design is political?

Of course you can interpret it if you are a person of politics, but that does not change the existence.

You can interpret the existence of a pebble as well, if you try hard enough.

I left the conversation there and did not respond. A cube is political because it can never be just a cube. In the case of “The Fungible,” the NFT that points to the image of a cube is a contract that lives on the blockchain, a decentralized network that amplifies and automates political choices on behalf of its users. Without its smart contract, the image of the cube doesn’t retain its cultural value or exchange value. This is true of every NFT, of course, but Pak’s work goes a step further by simplifying its iconography to extremely minimal forms (cubes, dots, a single pixel), so that critical attention shifts away from the image and back to the blockchain itself. The cube NFT cannot exist without the blockchain, and the blockchain is an inherently political system, one that the cube seems designed to help us notice and critique. Beyond that, “The Fungible” wasn’t just a series of artworks, it was a crypto onboarding campaign by Sotheby’s, a conscious effort to acclimate their traditional art world clientele to the accelerated, gamified world of NFT collecting. The cubes are inextricable from their technological, financial, and cultural contexts. My delayed response is yes, a cube is political, and so is a pebble, if you decide to call it art (or design).

If Pak’s provocations are not meant to be understood as poetic political gestures, then they feel hollow.

Above all, finding out that Pak prefers to evade the political implications of their work by hiding behind the veneer of design was a little disappointing. I like Pak’s art, whether they call it art or not. I’m holding Pak to a higher standard than other NFT creators because I think the work deserves to be taken seriously. I’m not advocating that Pak, or any other artist, limit their output to my notion of “correct” jingoistic political propaganda. All art has political dimensions, but most political sloganeering is not art, and it’s not worthwhile to pretend it is. Instead, my hope is that Pak and other leading NFT creators seriously wrestle with the reality that many supporters of their work—and the systems on which the work relies—are actively implementing new financial, technological, and (yes) political systems that will have vast implications for many, many people.

Pak is one of the few artists who are truly using the blockchain as a medium in compelling ways. NFTs are supposedly constant, but Pak introduces mutability. Pak takes our assumptions about NFTs and manipulates them as material for new artworks. “Merge” reads as a critique of both the assumed permanence of NFTs and their non-fungibility. Tokens with the same mass are indistinguishable from one another; they are non-fungible tokens that essentially operate as fungible ones. Pak’s $ASH and $ASH2 coins are even more explicit attempts to blur the line between unique digital artworks and non-unique digital currency. Collectors can “burn” NFTs to collect their value in a bespoke currency that can be used to purchase new works by Pak and select artists. These projects are political because they blur the line between art and money in a way that feels critical and self-aware. Pak’s work has the potential to map the political foundations on which all NFTs operate. But if these provocations are not meant to be understood as poetic political gestures, then they feel hollow. If Pak is truly a designer and not an artist, as they claim, these projects are little more than a marketing campaign for a new vision of libertarian decentralized finance. Manipulating the political qualities of a medium and then boldly declaring that you ignore politics is not a way to rise above that reality. It’s just an admission that you’re making something with a material you don’t fully understand.

Kevin Buist is a design strategist, curator, and writer based in Grand Rapids, Michigan.