Lenses on Glitch, Part 1

Four artists share the tools and approaches they have developed for working with glitch.

On November 3, MCH Group, the Swiss engagement-marketing behemoth behind the Art Basel brand, and the non-profit Luma Foundation headquartered in Arles announced the creation of “the first blockchain ecosystem built for the art community, by the art community.” Arcual, the press release said, is “born out of a shared mission to put artists at the center of the art ecosystem.” It intends to do so through “smart contract solutions” that will secure on-chain everything from the terms of sale, including artist and gallery royalties, to provenance verification and digital certificates of authenticity. In short, it purports to take some often-touted benefits of the cryptosphere—for artists, greater autonomy over sales; for collectors, standardized certifications of ownership and authenticity—and make them available them for the world of physical art, bringing a much-needed element of transparency to the notoriously opaque art market.

Arcual is far from the first start-up to attempt to make blockchains relevant for physical art collections. Verisart, Fairchain, and Lobus have each, in recent years, proposed to clean up the art market with blockchain, each making a virtually identical set of promises to those of Arcual. In September, the Swiss start-up SmartStamp launched its app, likewise professing to address concerns about authenticity and ownership through use of AI and blockchain. So what sets Arcual apart from its predecessors? A recent presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach provided little specific information about the complexity of the chain Arcual has written; a white paper is to be released in the first quarter of 2023 with more technical details and specifications. For now, as they demonstrated with a “live transaction” performed in Miami, Arcual has one unique selling point. This is a mechanism that they’re calling “two-factor authentication,” which means that artists will not be able to create a smart contract for their work alone. They would need a second party, usually a gallery, to send an input as well—an approach intended to combat fraud, offering more assurance to collectors.

There is no fundamental reason why an NFT shouldn’t authenticate a painting or sculpture rather than a jpeg.

Transparency and privacy; power for artists and protections for galleries and other stakeholders; “decentralization” as administered via a blockchain that has been built under the auspices one of the most powerful market forces in the sector: we appear to be deep in having-your-cake-and-eating-it territory. But how can blockchain technologies best be mobilized to the benefit of the art world, if at all?

Bernadine Bröcker Wieder, CEO of Arcual, spoke in Miami of the desire to “empower every participant” in the industry—but she also professed a more modest goal, that of achieving a “data standard,” and this is where Arcual may perhaps be on to something. Christiane Paul, professor of media studies at the New School in New York, likewise believes that the clearest potential benefit of blockchain is through “standardization” of museum and gallery practice for authentication and provenance. As Paul wrote for Outland earlier this year, the focus on NFTs as a sales mechanism has obscured their potential to record proof of authenticity on the blockchain. Smart contracts, that is, can encode something like the certificate of authenticity by which galleries and museums confirm that a sculpture or painting is by a certain artist, and in some cases that the work is in fact what it’s supposed to be—that, for instance, Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019) is Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019), and not just a banana and some duct tape. An NFT functions as a signifier for a work and not the work signified, so there is no fundamental reason why it shouldn’t authenticate a painting or sculpture rather than a jpeg.

What might be the benefits of storing a certificate of authenticity, along with any necessary information about provenance, conservation, or actualization of the work, on the blockchain as opposed to a museum or gallery’s collection management system (CMS)—or in a filing cabinet? For Paul, this is where standardization comes in. Museums and galleries have wildly varying protocols for collecting and storing data about the works they handle. The Whitney Museum of American Art, for example, has a notoriously long questionnaire for artists about acquisitions of time-based media work. But the problem extends to more traditional art forms; the information that has been collected about a painting or sculpture in different institutions fluctuates considerably. “One area where I see huge potential for the blockchain,” Paul said in an interview, “is metadata compatibility: the ability to exchange metadata on collection works.”

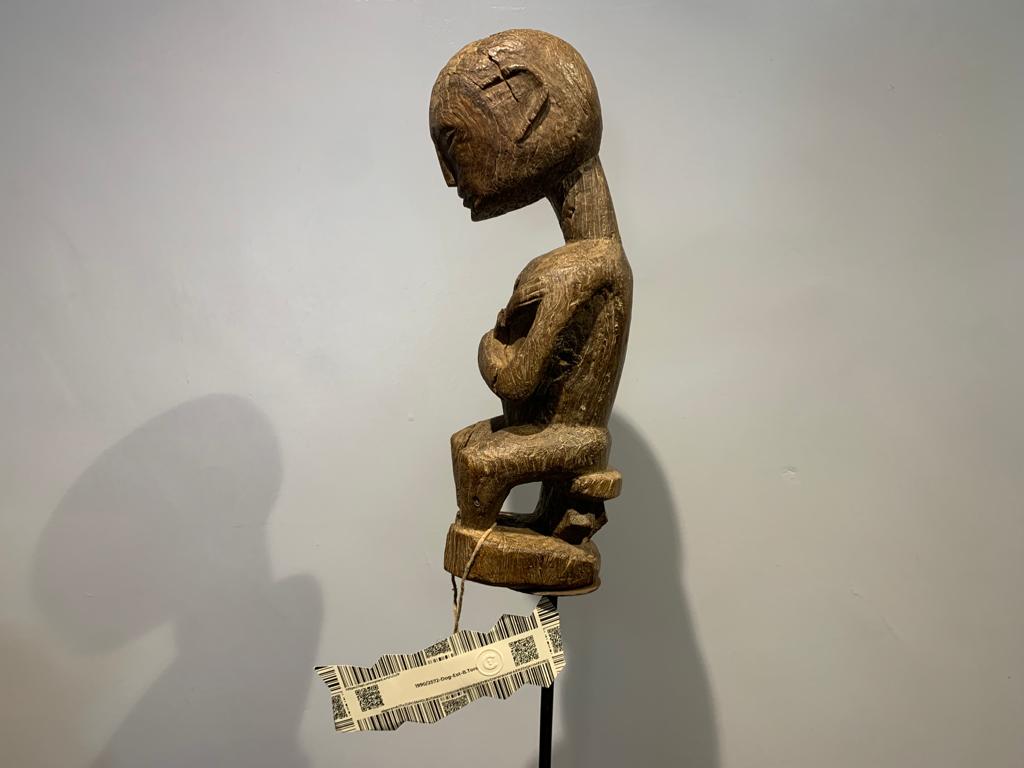

It is easy to imagine the benefits of a system of on-chain protocols that standardize the information that accompanies an artwork as it passes hands, from artist to gallery to private collector to museum. As well as setting an industry standard for data to be collected, there is the possibility of making this standardized metadata available on a public ledger to everyone from curators and art historians to invested amateur researchers. Uncopied, a venture founded by the Paris-based computer scientist Elian Carsenat, has demonstrated this “utility” in a recent collaborative project with the Sirius Art Gallery in Mali. A certificate of inventory for a votive statue in a private collection in Mali has been recorded on the Algorand blockchain and saved on IPFS. Uncopied originally intended to work with the National Museum of Mali in Bamako to certify further works but financial and logistical difficulties connected to the country’s long civil war, as well as the pandemic, have delayed this project, with the votive statue serving as a “pilot” case. A system that makes data on works held in collections with scant funding, or locked in war zones, as comprehensive and accessible as the data held by the world’s major institutions—while also being stored in ways that don’t rely on the continual functionality of servers—could be manna for art historians.

Museums and galleries have wildly varying protocols for collecting and storing data about the works they handle.

However, it is just as easy to see the challenges of using blockchain in this way. One inherent limitation is the immutability of blockchains. What happens when the record needs to be altered, whether because its condition changes or because an artist changes their mind—one thinks of the many lives of Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–23), for instance—or because researchers have uncovered new facts about an older one? This, according to Paul, is one of the key unresolved questions. (A spokesperson from Arcual told me by email that they “understand the need to update/amend/append artwork and provenance data” and “are considering and researching use-cases that require these actions.”) Other issues are perhaps more pragmatic—there are debates over whether a smart contract, which on Ethereum can include up to 256 kilobytes of code, can support the level of detailed provenance data, condition reports, conservation histories and so on that museums require. Supposing it were possible, how much energy would such complex information need, and how much would it cost?

Then there is the matter of trust. Paul was quick to point out to me that the use of smart contracts for institutions would be a supplement rather than a replacement for existing practices—indeed, Uncopied is exploring the possibility of integrating their API with museums’ existing CMS. But it would nonetheless take a leap of faith for institutions to entrust part of the historical record to this relatively new technology. It is notable that, while Arcual has announced the intention to work with museums in the future, for the moment it is confining its offer to commercial galleries, with the likelihood that it will be primarily geared at contemporary dealers selling new works for which the provenance record starts at zero.

This leads into the sometimes murky differences between museums and commercial galleries. While public availability of data is a clear boon for the former, for the latter it’s often anathema. Collectors don’t necessarily want the world to know that they own, say, the last great Rembrandt in private hands. And of course, multimillion-dollar assets secured on the blockchain will be a prime target for hackers. For galleries to do business, they need to be able to provide collectors with assurances that their anonymity is secure. Bröcker-Wieder explained in a recent WAC Labs talk that the blockchain Arcual has created will be private, at least to begin with. The plan is then to gradually decentralize as the ecosystem develops through the activities of legitimate parties and trust is established. This privacy will apparently make it easier not only for Arcual to root out any fraudulent activity that does take place, but also to clearly establish the codes of ethics that govern users of its chain—for instance, ensuring agreement among all its users that the tokens it mints have no secondary market value (unlike NFTs), but operate solely as digital certificates of authenticity, immutable provenance records, and enforcement of artist and gallery royalties. But there remain questions about the security of this information—as well as the safeguards that are in place to ensure artists get paid royalties. The Arcual spokesperson confirmed that they are working on compatibility with Ethereum—but this carries certain risks. In theory, it would be possible for a collector to burn their smart contract and remint it on Ethereum, meaning that any artist resale rights encoded in ways that the ERC-721 can’t host may evaporate.

From another perspective, the proprietary nature of its blockchain marks Arcual out as a deviation from the principles of artistic empowerment and decentralization that it professes to uphold. Regina Harsanyi, a specialist in the preservation of time-based media art and a curator at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, is a strident critic. “If the people behind this product truly, deeply cared about artists, their rights and royalties, they would just be fighting for something that’s open source or they would be banding together to create some kind of new improvement protocol, such as an Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP), on existing blockchains,” she told me. Harsanyi cited Billy Rennekamp and Sam Hart’s Cosmos—a protocol for inter-chain communications, as well as an “open software development kit” to build a blockchain—and Protocol Labs’ upcoming launch of the mainnet of their layer-one blockchain that works with Filecoin as “solutions that already exist.” “Protocols are supposed to be transparent and open and should be anti-custodial—or they’re not decentralized,” she said.

Provenance records are meant to last for centuries—and to put it lightly, blockchain’s staying power has yet to be put to the test.

More broadly, Harsanyi voiced skepticism about the potential for blockchain as an improvement on existing models for recording information about artworks. There is an important qualification here: museums looking to acquire significant works using blockchain as their medium need to update their CMS to adequately engage with the particularities of on-chain art. But beyond that, Harsanyi sees few real benefits of blockchain technology for how museums operate. “Would the museum want to ever use a blockchain for provenance purposes?” she asked. “It’s complete smoke and mirrors as a preservation tool in almost every regard.” Provenance records are meant to last for centuries—and to put it lightly, blockchain’s staying power has yet to be put to the test.

Time alone will tell whether the impressive promises that have been made for blockchain’s potential to transform the analog art world will translate into something more tangible, and what form that might take—whether, for instance, standardization of provenance data or artist resale rights will be in the foreground. But for the moment, the contradictory nature of these promises suggests that we may eventually find them too good to be true.

Samuel Reilly is assistant editor of Apollo.

Thanks to Simon Denny for granting permission to illustrate this article with images from Blockchain Future States (2016), an installation of imagined trade show booths for the crypto companies Ethereum, 21 Inc., and Digital Asset, in these images exhibited at the 9th Berlin Biennale.