Utopia Piece by Piece

LaTurbo Avedon is building a virtual world where the blockchain’s aspirations to decentralization and democratization can be fully realized.

For most of human history, social structures prevailed without statehood. Today such forms are endangered, as every modern state pursues the incorporation of non-state spaces and people. The South China Sea is one such battleground, where territorial disputes over islands, reefs, and the surrounding waters cast a shadow on traditionally sovereign ways of living. China’s claim over virtually the entire sea—through which about a third of the world’s maritime trade flows—is contested in places by Taiwan, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines, with additional involvement from the United States. Against this fraught political backdrop, Forkonomy() reimagines oceanic autonomy through a queer hackerist ethos. The project began in late 2020 as a workshop at Taiwan’s C-LAB, in which artists Tzu Tung Lee and Winnie Soon brought together policymakers, scholars, marine life conservators, cultural workers, artists, and activists to consider one question: “How do we buy, own, and mint one milliliter of the South China Sea?” Simple to the point of audacity, this proposition nonetheless launches a playtest for what it means to fight hostile legalities with codes—both computational and ethical.

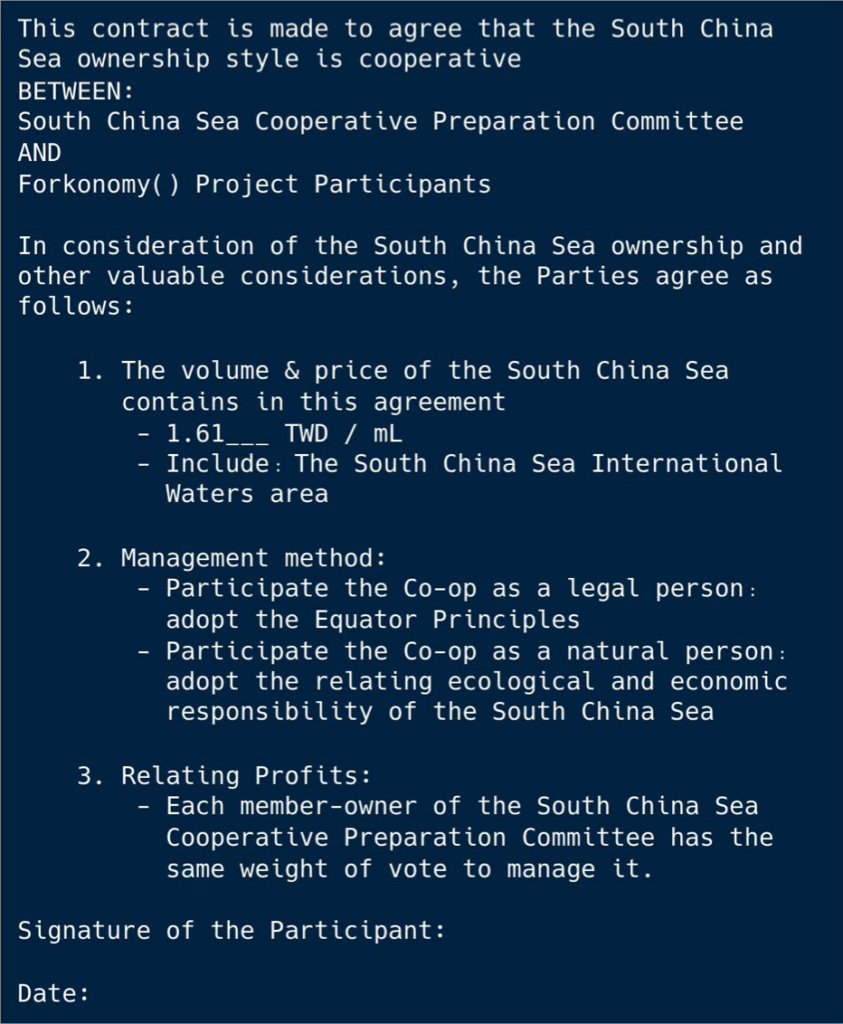

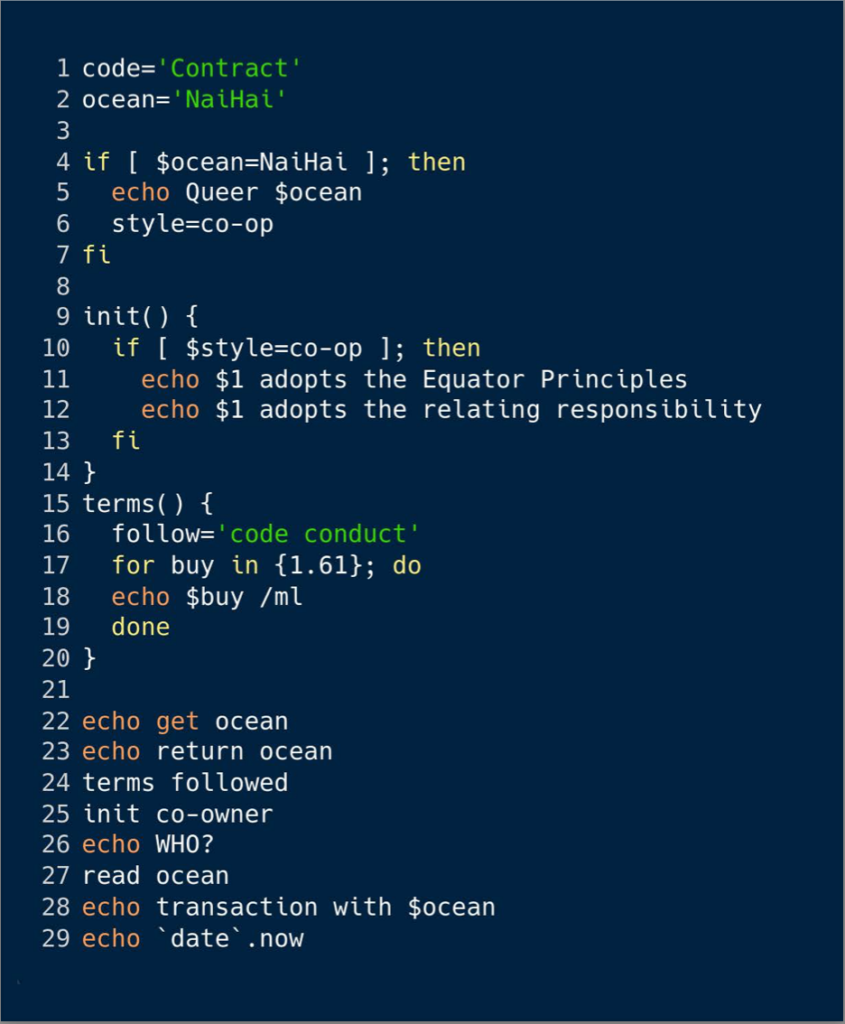

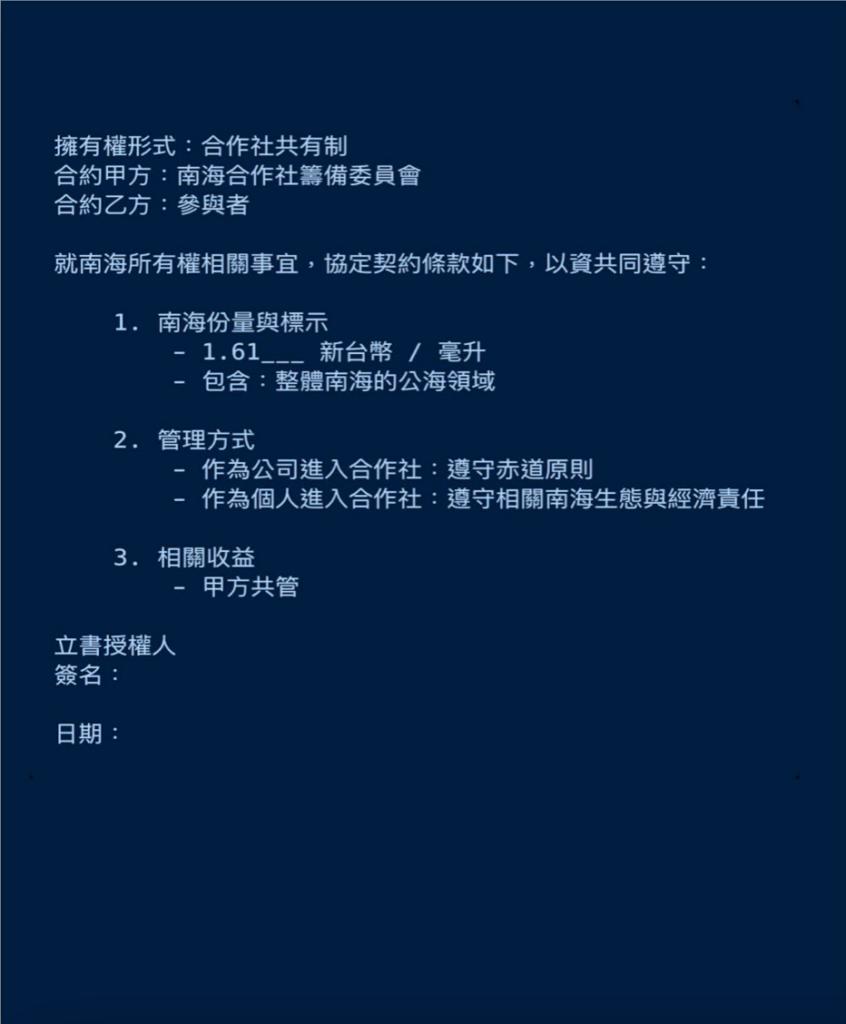

Forkonomy() takes its name from the software development process of “forking,” which means to copy the original code and start working on it as a separate project with its own community of developers. This is a powerful strategy in situations of collaborative deadlock; it can be enacted without permission in the case of open-source software or by pirating proprietary software. As state-led governance calcifies over the South China Sea, Forkonomy() seeks an alternative path forward. Through a series of workshops, participants agreed on a cooperative ownership model with a set price of 1.61 New Taiwan Dollars (TWD) per milliliter of seawater. A collectively authored contract, written in English, Chinese, and the Bash programming language, endows each purchaser with the material asset as well as ecological and economic responsibility for the South China Sea at large. The artists later published 10,000 editions of the contract as NFTs on the Tezos blockchain with the aim of using potential royalties to generate subsequent editions, such that the number of member-owners may grow to eventually fork the South China Sea out of its current nation-state binds. In the process of setting a price, signing a contract, and drafting a code of conduct together, workshop participants found themselves confronting daring questions: Who has the right to make decisions about the sea? Can the act of collecting be in service of a commons? What does watery liberation consist of?

Can the act of collecting be in service of a commons?

Growing oppression under the neoliberal and imperialist order has spurred a myriad of alternative organizational experiments in recent years, both on- and off-chain. The term “extitution,” originating from the networked urban commons movement of Madrid in the 2010s and later worked into organizational theory by Primavera de Filippi and Jessy Kate Schingler, helps name a strategic shift from the centralized enclosure of institutions toward more adaptive, decentralized dynamics. Forkonomy()’s ambitions call to mind related efforts, such as Indigenous-led movements to grant rivers and lakes legal personhood; the founding of community land trusts, agrarian commons, and platform co-ops; terra0’s speculative “self-owned forest”; copyleft licensing; and web3 tools for financing grassroots regenerative economies. The common challenge these organizers face is developing some sort of structure that can withstand existing legal and economic pressures while scaffolding a reparative zone within which more fluid and cooperative relations can thrive.

In manifesting “a queer ocean of freedom,” Forkonomy() also pays homage to the influence of transfeminist activism in shaping more robust codes of conduct practices in free and open-source software (FOSS) cultures. FOSS has historically struggled with sexist and racist online behavior; meanwhile, LGBTQ communities have pioneered the conjuring, both online and offline, of “safe spaces,” through the explicit statement that violence, harassment, or hate speech will not be tolerated. It is to the credit of organizations such as Ada Initiative that codes of conduct have proliferated across open technology and culture projects—“confront[ing] systemic oppression through the work of articulation,” as artist and Forkonomy() co-owner Femke Snelting puts it. Lee and Soon invite a conspiratorial process that carries on this lineage, as workshop participants have come together to define expected and unacceptable behaviors in hopes of warding off harmful interests while sustaining a fluid confluence of identities and activities in the South China Sea.

To cast some liberatory spell for the ocean is beyond a question of necessity, but who holds the power for such incantation? Following the now-too-familiar priorities of the speculative crypto market, it is not difficult to imagine this invitation to own the South China Sea quickly devolving into an investment grab by faraway technocrats and the beginnings of a dystopian network state. Even with the best of intentions, if the new owners possess a merely trivial understanding of what stewardship truly entails, the sea’s fate may be cursed to nothing more than that of a goldfish brought home in giddy haste from a day at the carnival. As financial wealth and technological access are already concentrated in the hands of the elite, how might a project like Forkonomy() take care to prevent the further disenfranchisement of the sea’s existing community of stakeholders?

The internet is not unlike the ocean in its strange ungovernability, and there lies across both a potentiality of rogue organizing.

Under contemporary factors including degrading coral ecosystems, depleting stocks of fish and other goods, increased market tensions and militarism, and the geoengineering of artificial islands by the Chinese government, traditional ways of life have become more difficult to sustain. It would then be remiss to not consider nested strategies of resistance that can respond at the scale and power of intergovernmental forces. As demonstrated by rapid response projects like UkraineDAO, a tangible vehicle can funnel solidarity from afar, and the South China Sea needs all the friends it can get. Lee and Soon hope to evoke through Forkonomy() the possibility of building power across many roles and positions of support. As Lee wrote last year in an essay for Makery: “Imagine if the dotted lines on a map were no longer representing the competition of territorial boundaries and colonial powers, but for people and communities to make and maintain connections.”

Artist Amelia Winger-Bearskin has issued a call to “code our morals.” This can prove difficult in practice. Drafts of the Forkonomy() code of conduct reveal tricky nuances as participants wrestled with what should be formalized as expected behavior between the practicalities of anonymity and transparency, situated knowledge and monitoring at scale, shared ideals and heterogeneous norms, and so on. As an ethical framework for software development based on the Iroquois practice of recording agreements, Winger-Bearskin’s Wampum.codes serves as a possible reference for how to articulate the commons by software terms. In this framework, an open-source project carries a json file in which the developer would repurpose prompts like “Start,” “Test,” and “Build” to inscribe specific value-based intentions, non-negotiable limits, and real-world dependencies that guide appropriate use. Such categories may help to situate some of the initial wishes and concerns of Forkonomy() participants while allowing for future adaptations as needed.

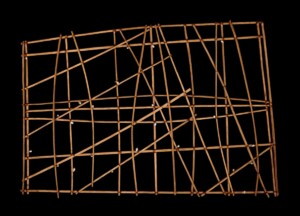

While the protective frame of Forkonomy() may position the South China Sea in a mode of resistance legible to anthropocentric systems of power, the ocean itself evades the shape of a border or the accounting of an asset. Navigational charts from the Marshall Islands testify to what Phil Steinberg and Kim Peters in 2015 defined as “wet ontology.” In contrast to two-dimensional cartography, these arrangements of sticks and cowrie shells allude to a way of mapping that is subjective, embodied, and born of the fluidity of ocean swells. As such, it is unsurprisingly difficult to set a cost to the waters. In Forkonomy()’s survey of preliminary prices, participants suggested that a milliliter of the sea might cost anything from nothing to the price of a cup of boba to 10,000 TWD (with a snarky discount of “buy a thousand, get a hundred.”) Though eventually agreed upon and minted, the price graciously resigns to the realm of poetic gesture to surface a reminder of truer relational terms.

It’s not a coincidence that the term phishing comes from fishing and pirates from the sea. The internet is not unlike the ocean in its strange ungovernability, and there lies across both a potentiality of rogue organizing. Perhaps instead of a united front, a truly protective “fork” seeks to simulate the technology of cell membranes. The Forkonomy() contract for the South China Sea itself can be taken as open source, replicating across translocal groups to make many situations of fugitivity possible, until they ultimately corrode the very notion of ownership itself.

Alice Yuan Zhang 张元 is a Chinese-American media artist and cultural organizer.