Kanon

The K21 collection identifies significant works of digital art and aims to preserve them for the next hundred years.

Institutions that focus exclusively on exhibiting and collecting software-based art are relatively rare—in part because the history of this art is still being defined, and also because maintaining such works involves special technical knowledge and care. HEK (House of Electronic Arts) in Basel, Switzerland, is one museum committed to this field and the questions it entails. Sabine Himmelsbach, a curator with a long record of working with media art, has been HEK’s director since 2012. She spoke to Outland about the challenges of preserving software art made in the era of Web 2.0—with tools and interfaces that are subject to constant change by their corporate owners—and how HEK is embracing the opportunities of web3.

HEK is a relatively young museum. It was founded in 2011 as the merger of its predecessor institutions: Plug.in Forum for New Media and Shift Festival of Electronic Arts. The idea was to complement those festival programs with a collection. We are the only museum dedicated to media art in Switzerland. When I got here and started to work on the collection, I asked: what kind of difference can we make? Software and net art were missing from many public and private collections in Switzerland. That’s where our focus is, but the field is quite complex, as you can imagine. Software and hardware change rapidly. As an institution, we have to make sure that this digital heritage of ours is canonized and recognized.

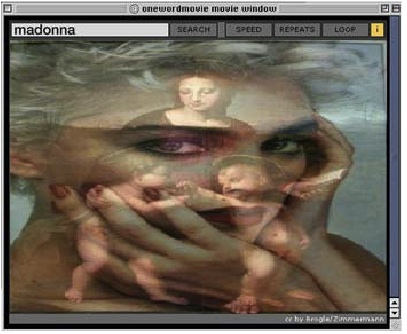

One early work that we collected was onewordmovie (2003) by Beat Brogle and Philippe Zimmermann. The artists approached us because they needed help keeping the work alive. We took it on as an important piece of Swiss media art history and used a two-part strategy. We migrated the piece to the new standards, so that it can continue to do what the title says: the work draws results from a Google search to create a movie. But migration always is a temporary solution to the problem of distributed obsolescence. It is dependent on the strategy and policy of Google. So we also produced an emulated version with the look and feel of using a Google search in 2003. We added a database where we collected all the searches made by users while the piece was being restored. In the years to come, we will have a quasi-interactive version, where all the images and data found at that time can still be retrieved. This has been a major undertaking.

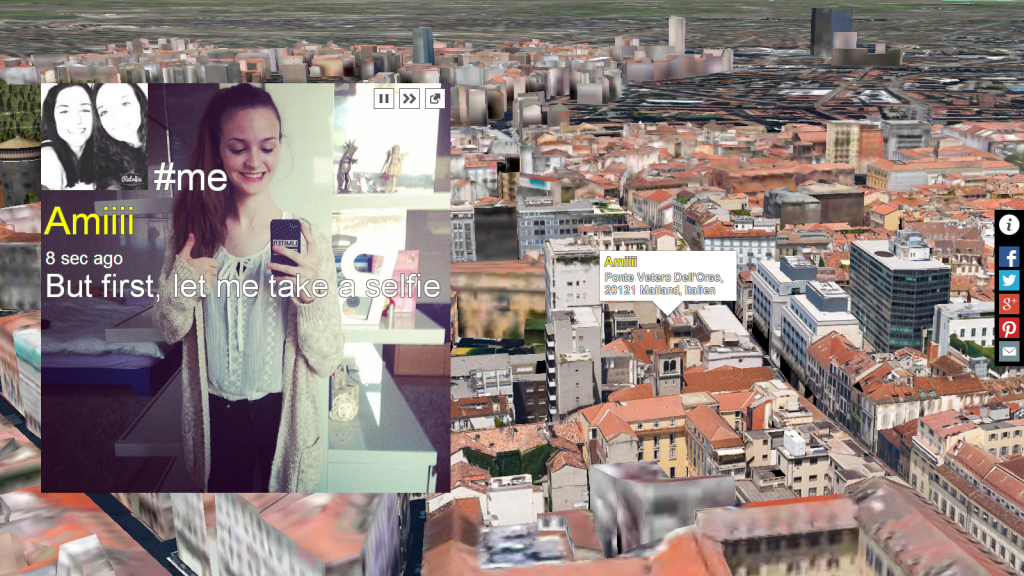

Marc Lee’s works TV-Bot 2.0 (2010) and Pic-Me (2014) are also very interesting. Usually, as an institution acquiring a work, we would handle the preservation, either migrating the work or emulating it. But Lee’s approach is that if he sees a work is no longer functioning, he versions it and calls it Pic-Me 2.0, for example. That leaves us as an institution with a static work. There’s no need for us to migrate it.

Every year we do a case study on one of the works from our collection that showcases conservation strategies and models. With software and net-based art, there’s no one solution. We’re now in a working group of several museums, including Tate Modern, that addresses virtual reality projects. We have an early VR piece by Mélodie Mousset, We were looking for ourselves in each other (2015). It was made for Oculus Rift, which was acquired by Facebook. It’s not clear how long it will be supported. So in the research group we are working on 360-degree video documentation as a preservation strategy. It’s important to understand that you cannot tackle these issues on your own. You have to be in a network of partner institutions because we all are facing the same problems.

At HEK it’s clear that NFTs are becoming a part of the kind of work we collect. But NFTs are certificates of authentication. There are on-chain NFTs, which arguably use the blockchain as a medium, but for the most part NFTs have to do with how the art is handled. There’s no such thing as Visa art, right? So I’m not sure “NFT art” is a good term, because it really just refers to how the digital asset is managed. For younger audiences, buying NFTs is about having a collection on your phone. Sometimes the app doesn’t even retrieve the data—it just shows how the NFT is featured on a platform. For a museum, things have to be clarified. Where is the digital asset? How is the NFT mechanism making it secure?

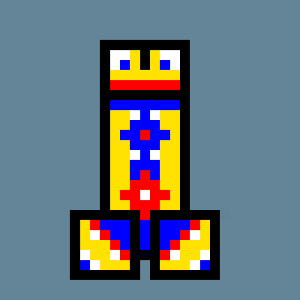

What interests me for HEK’s collection are works that look at the intrinsic qualities of blockchain technologies and how artists are tackling them with NFTs. I see it more like early net art that has embraced what’s possible on the net, from distribution channels to self-marketing. What is this new space? How is it connected? What utopias are imagined there? The first two NFTs that we collected are by the group Ubermorgen, from their project The D1cks (2022)—pixelated drawings of penises as an ironic gesture toward the PFPs that were so popular last year. And clearly it’s making fun of the male dominance in the NFT sector, with a rude gesture that’s like giving the finger. The work is fun but it also has many layers.

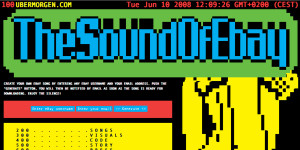

We have an older important piece by Ubermorgen, too: The Sound of eBay (2008–09). We’re currently showing it along with The D1cks in a new online exhibition space that we just opened at virtual.hek.ch, where we try to tell the history of our collection with several works spanning from Web 1.0 to web3—and trace how artists have addressed issues of representation from social media to the decentralized web. The Sound of eBay is a huge project by Ubermorgen to sonify the online marketplace. We only have part of it. When they work for several years on a huge project—how do you price something like that? We decided to acquire bits of data that they put together especially for us.

We’re developing our strategy to move forward in web3. We want to establish a HEK DAO in the next six months. Like many institutions, we realized during the pandemic that our outreach was limited when the borders were closed. Basel is a small city—just 200,000 people. Through the DAO we hope to reach a younger, global audience that is passionate about media art, and invite them into our decision-making process. As part of the DAO’s activities, we also want to produce NFT editions connected to our program. We minted one NFT with the artist Ursula Endlicher, who is part of our current exhibition “Earthbound: In Dialogue with Nature.” She has created a digital interface in the exhibition space, which is about ecology and the trees on the square outside HEK. By using an AR app, you can go outside and scan the bark of the tree, then access the NFT. It links physical and digital space.

In their book Radical Friends (2022), Ruth Catlow and Penny Rafferty say: “Blockchain technology continues to secure billions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency and cannot easily be unthought or unbuilt. Culture will therefore be shaped by those who engage with it.” We can either be part of it and try to shape it or shy away and not do anything. Now is the moment to try to shape it. That’s the agenda that we’re pursuing.

—As told to Brian Droitcour