Gestures of the Generative Painter

Simulated brushstrokes have long appeared in digital art. But generative art's expressivity is less about imitating painterly gestures than devising a system to produce them.

Some art is legendary. There are works of art that we hear about more than we ever see in person or even in reproduction. I’m thinking of some of Jeff Koons’s most production-intensive projects, like the Train that would have replicated a life-size steam locomotive only to hang it vertically over the street from a crane; it bankrupted his production house, or so the story goes. Sometimes these works, which we hear about in whispers, tell us something novel about an artist’s background or process, like Takashi Murakami’s early installation of a rocket engine glowing against the floor in a dark room. Supposedly it’s full of pathos and gravitas and lends a sinister glint to the enthusiastic grins of most of his ensuing work and has never been lent out by the institution that owns it. I say “supposedly,” because of course I’ve never seen it. It lives in legend.

I offer this as a preamble to James Jean’s Pagoda not because it doesn’t exist yet, but because it seems to be a characteristic of the work itself that it is destined to make its way out into the world in the form of fragments, whispers, sketches, reflections, and refractions. It is a work I’ve been anticipating based on word of mouth since smaller stained glass structures began appearing in James’s exhibitions, like the luminous Gaia (2019), a golden obelisk standing tall above visitors to his show at Seoul’s Lotte Museum. Pagoda, we’re told, would blow all these out of the water, an architectural environment with space for a dozen people—disciples? worshippers?—to fit inside at once. And so now it comes as no surprise that the seven thousand panels of Pagoda will be preceded by Fragments, NFTs similar in design to the panels that also number seven thousand. NFT drops are the whisper campaign par excellence of 2022. A legendary structure dispersed through the ether in thousands of digital fragments. Everyone is talking about it, but no one has seen it. Everyone wants it, but no one really knows what it is.

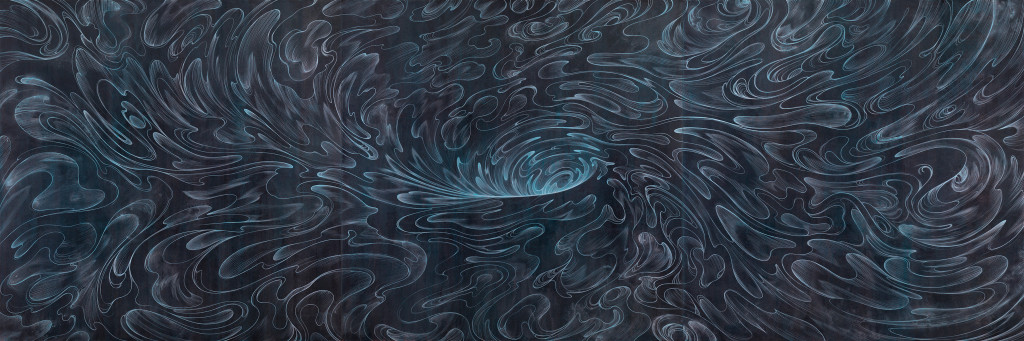

I’ve been spending time recently thinking about Jean’s painting work—specifically, I’ve been captivated by the massive paintings from 2019—Stampede, Bathers, Passage, Whirlpool, and the ongoing series “Descendents”—more than three meters high and some nine meters wide, a format that splits the difference perfectly between the cinematic, the mural, and the scroll. They’re indeterminate in the best sense of the word: we can move through them from left to right or right to left as if we’re characters navigating a landscape, and we can see narratives playing out across them via a very real sense of everything happening all at once. We are immersed within them as much as we feel ourselves positioned as heirs to a tradition that is forcefully conveyed, invented, fabricated—for the fact that we can see these myths making themselves in the process of being read and understood is one of the things that makes them what they are. As far as the Fragments are inspired by the stained-glass panels of Pagoda, they read a bit like the icons of Christian traditions, pocket-size images that refer back to a larger universe and suggest the bearer’s belonging to a wider community. That is what the PFP does as a medium today: it stands in for its bearer’s own face, and in doing so proclaims affiliation—even the sublimation of the self. You can take your PFP with you when you go, and it can take you places too. If Jean gives us a new epic tradition in which we can find models for aesthetic life today, its core values are these: we can be who we choose to be, and our identities are defined by our choices more than our circumstances; we can choose our own ancestors, and the history that culminates in the moment in which we live is a malleable and plastic one; we can define the aesthetic universes that give us sustenance, feeding on the very same myths and legends.

A world is built when its history becomes a shared heritage and its future can be evenly distributed.

This brings us to the worldbuilding aspect of Jean’s practice. Worldbuilding is one of those things that every artist, every creator—every child or teenager for that matter—aspires to before realizing how much labor actually goes into it. Internal consistency is hard, and reverting to normative baselines is easy. The epic paintings that captured my imagination might be best understood as the history paintings, the national galleries, the cycloramas of the alternative universe in which Jean’s alter ego as an artist resides, but there’s a self-awareness to the fact that these are the products of a very personal imagination. In reviewing a few hundred of his compositions I started taking a count of features: a menagerie of beasts real and fictional; recurring characters who appear in different places and times; graphic flourishes that signify particular economies of attention; colors that build different moods and allow for distinct sets of rules of physics based on what kind of medium they’re deployed into. These enormous paintings might be my personal fetish objects of Jean’s universe, but they’re just one component. There are also digital spaces, monumental sculptures, smaller paintings, and what could be described as design objects, an aesthetic diaspora so overwhelming it barely holds itself together.

In a way I suspect that this is the marker of a successful worldbuilding endeavor: we see drips of it leaking out into our other aesthetic universes, we note the resonances of where our traditions dovetail with its mythologies, we lose track of where one world ends and another begins. We mix up the actor and the character. We replace the soundtrack with live accompaniment. The whispers of legend become indistinguishable from the materiality of the work. To contain it would be to control it, a folly to which many of our most brilliant artists have given themselves over in attempting to craft the ideal environments for viewing their work, like the Rothko Chapel or Judd’s Chinati Foundation or Turrell’s Skyspaces. What the contemporary impulse seeks is an outward explosion, a generosity of spirit that trusts its viewers to accept and remake, to collect and remix, to role-play and reimagine. I can imagine the Pagoda shattering before it is built, thousands of faces distributed by the wind like so many pollen grains seeking fertile ground. To become a denizen of this parallel universe is to take part, to accept in our own space-time the partial histories, personal stories, and recurring dreams and nightmares of Jean’s cross-cultural genealogy. A world is built when its history becomes a shared heritage and its future can be evenly distributed.

Robin Peckham is a writer and curator based in Taipei. He is co-director of Taipei Dangdai Arts & Ideas, and previously served as editor-in-chief of LEAP.