Gestures of the Generative Painter

Simulated brushstrokes have long appeared in digital art. But generative art's expressivity is less about imitating painterly gestures than devising a system to produce them.

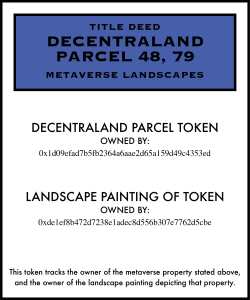

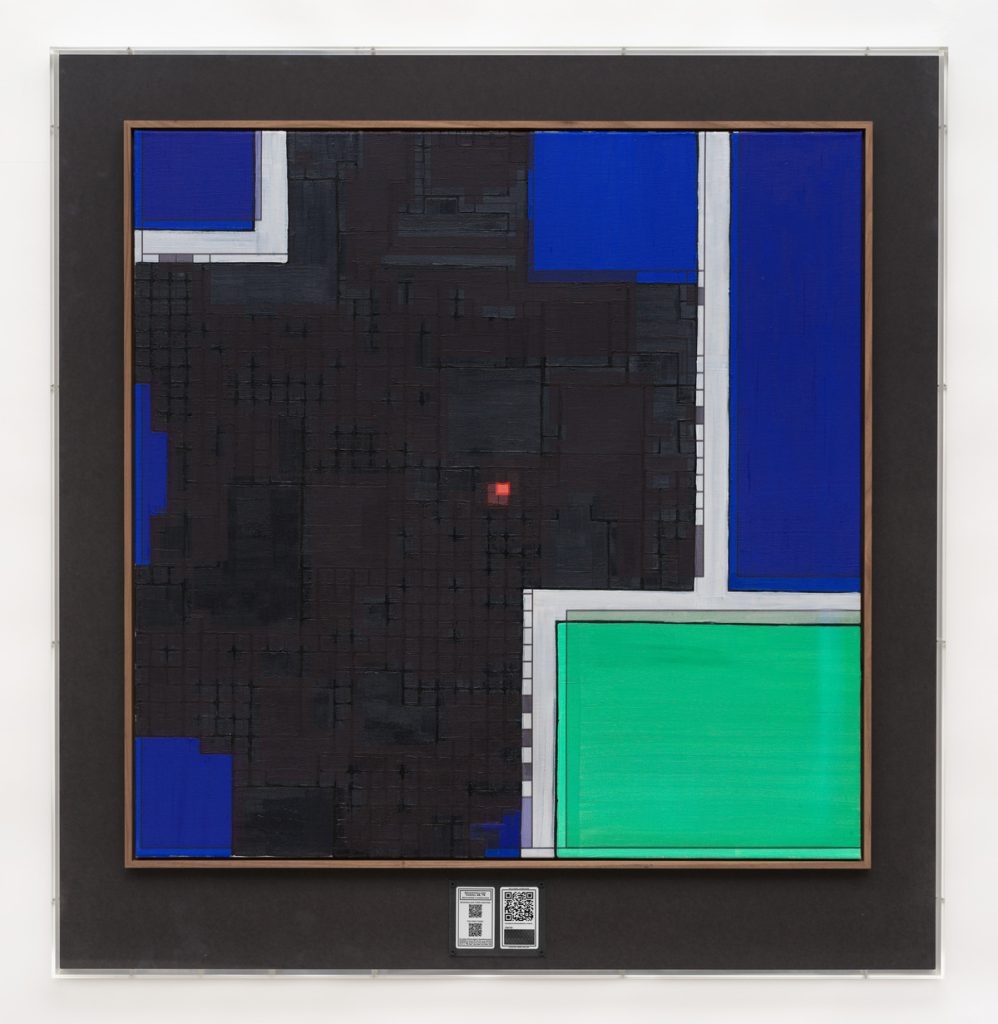

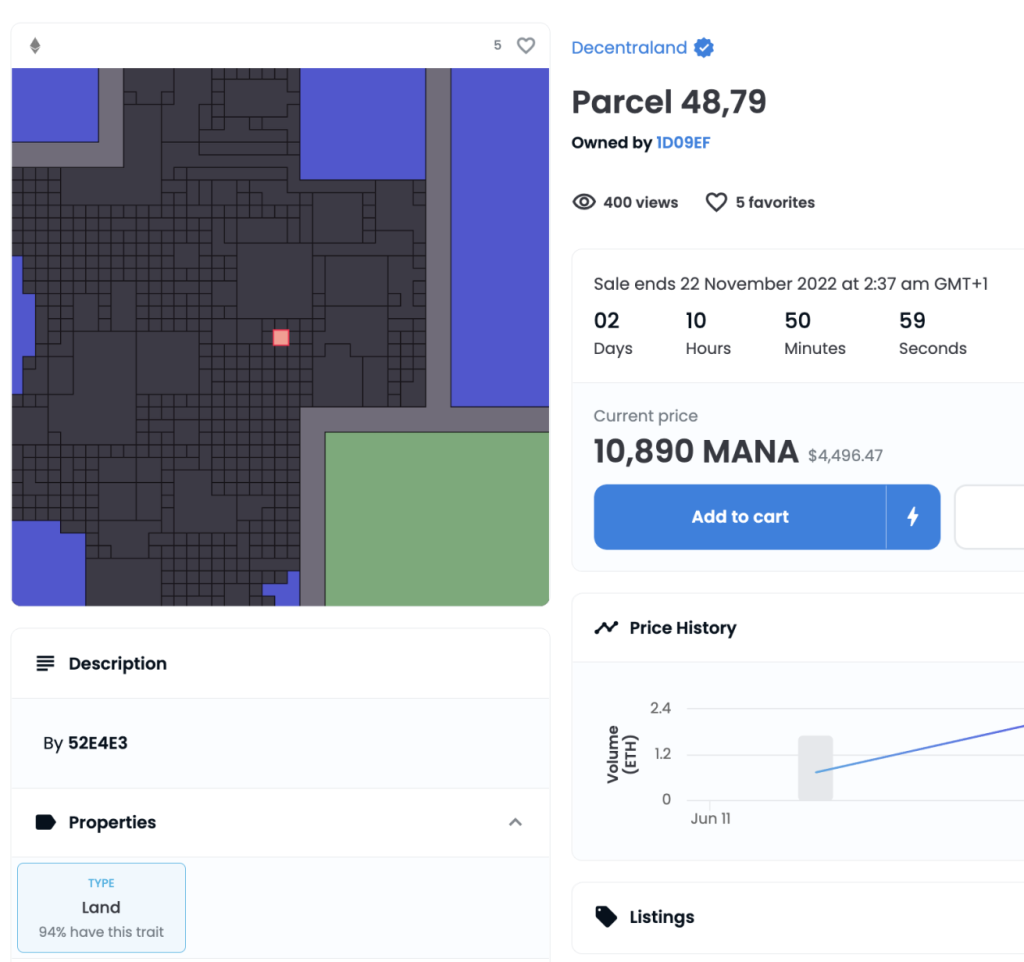

Simon Denny isn’t the first artist of the post-internet generation to pivot to that oldest and most saleable of analog mediums, painting. But he’s one of the few to have done so with dignity and mordant wit: the New Zealander’s Metaverse Landscapes (2022) don’t constitute anything like a quick cash grab, even if what they depict might. Specifically, Denny’s primarily oil-on-canvas paintings, which superficially resemble geometric modernist abstractions—changeably gridded divisions of the canvas square—are in fact representations of digital real estate and corresponding tokens from the Decentraland metaverse, where users buy NFTs that confer ownership of “parcels” of virtual land. The canvases reframe and expand the notion of landscape painting into god’s-eye map views, quadrant by quadrant, of this growing digital topography: the object, of course, of a recent speculative gold rush of sorts. At the base of each framed canvas is an Ethereum paper wallet, linked to a dynamic NFT that tracks, in real time, dual ownerships: that of the painting itself, and that of the land token. Painting might seem an incongruous medium for reflecting on such intangible transactions; or, alternatively, a perfect one for reflecting on how temporarily hot properties change hands. Denny’s series of canvases here make the case for the medium’s relevance: in their own hybrid way, they move, adapt, record, and—perhaps—side-eye.

That his Metaverse Landscapes resemble century-old static objects is part of their rug-pulling. Arguably, though, their aesthetic and rhetorical heritage runs deeper than that. When Denny’s painting/NFT bundles debuted late last year as part of the much-admired group show “Peer to Peer,” a text accompanying their launch suggested that landscape painting as a form of legitimation for claims to ownership goes back to the work of nineteenth-century American landscape painters like Albert Bierstadt. Art, it’s suggested, has long been used to naturalize “new” or contested landscapes, and not just real ones; modernist abstraction pointed to other realms—utopian ones, spiritualist ones—to give them credence in our world. The latter might be counted as a positive thing, and the equivocation or circumspection baked into the Metaverse Landscapes—that blockchain technologies have positive and even idealist aspects but can also enable old-fashioned avarice and the furtherance of hyper-capitalism—has been characteristic of Denny’s art over the past decade.

In speaking a language that art audiences know well, Denny’s new paintings continue his long-term project of giving physical, legible shape to covert and even formless information, processes, and forces that determine, albeit often invisibly, our daily lives. His breakthrough project, 2015’s “Secret Power”—presented, most notably, in the New Zealand Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, six years after Denny graduated from Frankfurt’s Städelschule—constituted a flood of visual and textual information relating to the Edward Snowden leaks that exposed New Zealand’s clandestine assistance of the United States in its intelligence-gathering work, as part of the so-called “Five Eyes Alliance.” In 2016, Denny established himself as one of the first artists working with blockchain technologies and the ideologies underpinning them. The pop art–tinted, fan art–themed sculptural installation Blockchain Future States (2016) traced the history of blockchain from supposed inventor Satoshi Nakamoto through cryptocurrency’s roots in gaming and up to its uses in various possible contexts (banking, tech, and an idealized, postnational digital society). The artist’s circumspection, or hedging, has deep and sometimes ethical-looking roots.

That the Metaverse Landscapes resemble century-old static objects is part of their rug-pulling.

For example, the visual for Denny’s first NFT, NFT Mine Offsets (2021), presented a rendering of a cryptocurrency mining rig that wasn’t used for the energy-intensive mining of crypto but donated by Denny to climateprediction.net for climate modeling. For Economist Chart NFT (2021), in collaboration with German economist Moritz Schularick, Denny used the latter’s most famous chart—concerning house prices since the 1970s, which have really only gone in one direction—as something like a meme, albeit a comically nerdy one. He then returned the profits to the Kunsthalle Basel, where the work was presented in a neo-conceptualist group show entitled “INFORMATION (Today),” and the environmental governing body of the institution’s host city.

Talking about that work in an interview at the time, Denny noted that he was interested in the possibilities of NFTs as vehicles for conceptual art and added that he’d been looking at the diagram-based paintings of Bernar Venet. It’s not hard, from there, to make a jump to the Metaverse Landscapes—particularly via what happened in between, i.e., last year’s cryptocurrency crash. His recent twofers step nimbly around the toxic-feeling detritus of NFTs as static or looping tokens, weightless digital artifacts that are easily stolen to boot, and lean into dynamism. Whatever happens in the marketplace—of NFTs and of “land” in the metaverse, which purports to be finite, but that’s only the case if you stick to one platform—Denny’s work here should stand as an adroit hands-off tracking of what’s coming down the pipe. It’s an objective record, for now, of human inventiveness, of wild hubris, or whatever else between.

Plus, just as if the value of said metaverse land goes down, you—addressing the collector here—are not on the hook for it, then if the value of the NFT goes down, you’ve still got the painting (or you’re the latest to have it, with crystal-clear provenance). And the painting itself, which perhaps needless to say is in a semi-comical value competition with its companion NFT, constitutes a meaningful land claim of its own, on the artist’s behalf. What “landscape” means has been irrevocably altered by the conception of the metaverse’s digital doubling—or, rather, multiplying—of it; Denny, in painting this digital space as overviewed and “owned” but also a near-abstraction, has effectively invented a new modality of landscape art. Whatever values wobble around the Metaverse Landscapes, that one feels stable.

Martin Herbert is a writer and critic based in Berlin.