Tactical Homebrewing

The movement to queer and decolonize fantasy roleplaying games has found inspiration in familiar methods of vernacular game design.

With its soft launch last spring, Liberland Metaverse joined a growing number of technology startups, web interface companies, and distributors of conceptual architecture projects competing to offer a more visually rich digital environment for videoconferences, social media, shopping, gaming, and public events. In principle, these platforms—among them Decentraland and Spatial—would support user interaction within a three-dimensional audiovisual network. This so-called metaverse or web3—essentially, 3D internet—might imaginably combine functions of Zoom, Facebook, Google, TikTok, ArtNet, and Evite into one seamless graphical interface. Most of the projects up to now are more or less stylized mockups, limited by the cost of developing the software tools, purchasing computing power, and achieving data speeds required to process hi-res 3D renderings in real time. Some of the “worlds” are being sold as NFTs on platforms like Mona. Liberland anticipates renting out rooms and offices for creative workers within larger building- and- city-like agglomerations meant to have a counterpart in the physical world.

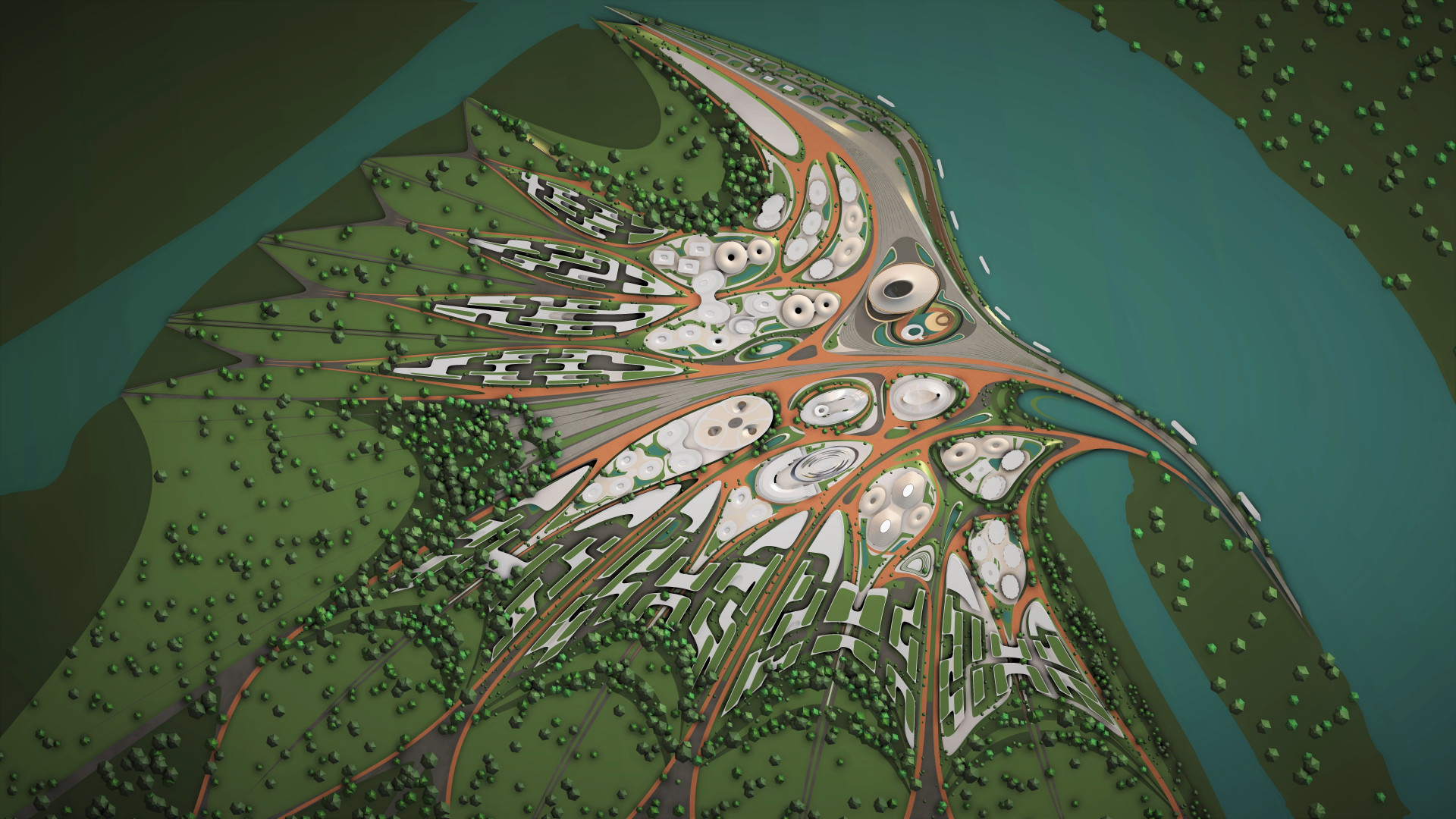

Led by Patrik Schumacher, principal and chairman of Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), the Liberland Metaverse began as a collaboration with the Free Republic of Liberland—a proposed libertarian micro-state located in a no-man’s-land of former Yugoslavia disputed between Serbia and Croatia. The currency would be a crypto coin called the “merit.” Since it was founded by Czech politician Vít Jedlička and his partner Jana Markovicova in 2015, the 4.3-square-mile territory on the bank of the Danube River has remained unpopulated (although it has received around one million applications for citizenship). Some more tangible progress has been achieved by the Liberland Metaverse, which is still in development, in collaboration with Daniela Ghertovici, founder of ArchAgenda, and Mytaverse, which offers a cloud-based platform focused on high-end product marketing and customization. ZHA has invested time in it through its computational design research studio, run by associate director Shajay Bhooshan, and Schumacher promotes its development through the Architectural Association School of Architecture’s Design Research Laboratory, which he also directs. So far the work-in-progress has gone live for two events, including this summer’s Floating Man Festival—an annual event in Liberland featuring bands, sport competitions, competition and blockchain workshops, AI art presentations, and a conference. A video tour of this virtual realm, powered by the Mytaverse platform, can be viewed online.

Liberland Metaverse maintains the fiction of a virtual-reality horizon: gravity-bound worlds are more familiar to users and easier for them to navigate and identify themselves within.

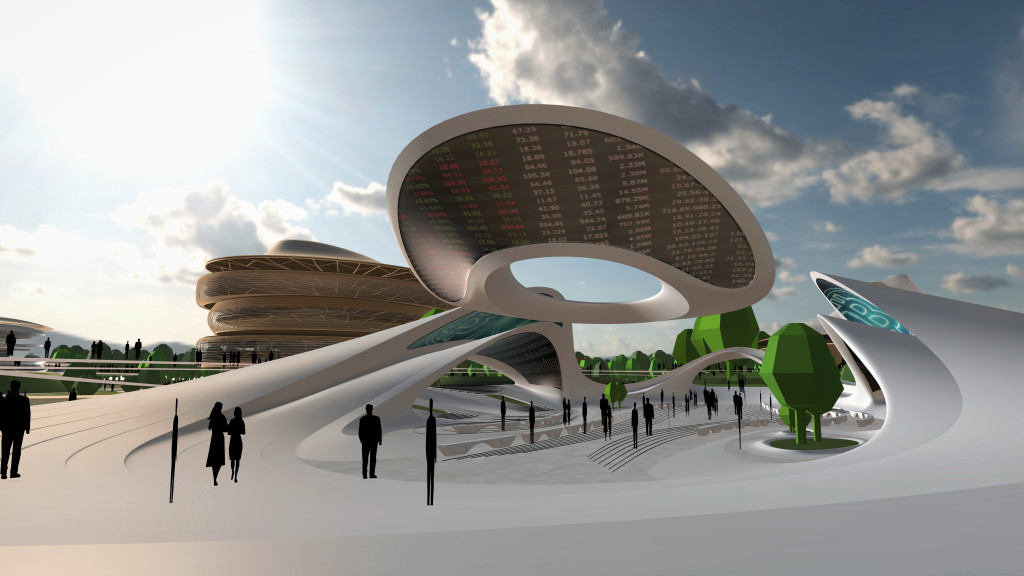

Metaverse architecture need not be limited by the physical constraints of real-life buildings. The previous era of modernism liberated itself from orthogonal forms by steel-reinforced concrete. Now, rules of gravity need not apply. Some of the design tropes of metaverses, such as the tendency toward depersonified bird’s-eye views and the absence of doors and windows, emerge from the peculiar characteristics of purely computational design. Yet Liberland Metaverse maintains the fiction of a virtual-reality horizon: gravity-bound worlds are more familiar to users and easier for them to navigate and identify themselves within. That may explain why its visual language resembles ZHA’s well-known commissions for high-end condos, hotels, and cultural institutions, favoring a curvy, blobby, parametric morphology driven by computer-aided design software and influenced by Russian constructivism and post-Corbusian architecture. For the sake of legibility, the site plans and layouts use recognizable filters of spatial division and threshold indications.

Schumacher has an acute sense of the possibilities and limitations of attempting another set of navigational and linguistic cues that would emerge from the new context—what he calls a semiology of the virtual world. “We can’t leap into a totally unfamiliar world where we’re not even bodies without a front, back, and an axis of orientation,” he told me. “It takes a long time to learn to navigate a social world and read situations, understand the setting, what are the protocols of interaction that come with the setting, and how they work as a distributed order or arrangement. We can’t lose all of that.”

Eventually, instead of browsing through scripted pages, links, and scroll-down menus, Schumacher anticipates the medium will allow for a more fluid movement through space in which denser content is accessed more intuitively. The idea is to offer more choices and opportunities for unplanned encounters, intense and empowering experiences, and a more productive use of time. “I’m not looking at the metaverse for thrills or experiences as such,” Schumacher said. “It should be beautiful and stimulating, but this is a place of communication and work, of cultural exchange, of collaboration, of information, exhibition, both professionally and educationally, as well as more informal social interactions. It’s a bit like upgrading our online lives.”

Yet Liberland Metaverse appears to suffer from some of the same computational design affectations and user-interface flaws that leave so many other metaverse concepts lacking. Virtual reality headsets have not yet been popularized and many people, including Schumacher, doubt their potential for widespread adoption in their current form. In their absence, navigation of 3D environments is awkward and lacks a compelling reason to exist. Why do the systems enable the horizon to rotate up and down so that figures face an imaginary sky or ground? Why do they all look like cheap video games? Why are the keyboard controls rudimentary pre-Atari-age up-down, left-right buttons? Do my professional friends, colleagues, and I really want to be embodied by childish-looking avatars?

Do my professional friends, colleagues, and I really want to be embodied by childish-looking avatars?

Another burden on Liberland Metaverse is its unconventional—or in a way, entirely conventional—politics. Schumacher has achieved a degree of notoriety in the last decade by associating himself, provocatively and seemingly uncritically, at times, with a particularly naïve-sounding free-market fundamentalist theme of libertarianism: If there were no regulation or governments picking winners, individual consumers would naturally sort out everything through free competition. It’s the most widely adopted theory of economics underpinning nearly all state-run central banks. Set interest rates, pump out cash to private banks, and let the market sort the rest out.

In extended conversation, Schumacher’s earnestness makes him a more sympathetic figure than the sometimes-vicious social media diatribes against him suggest. He recounted to me his intellectual journey, beginning as a youthful German leftist aligned with Marxism and Trotskyism, then discovering systems theorist Niklas Luhmann, witnessing first-hand the inadvertent negative impacts of planning regulations as a professional architect, and finally dealing with the mortgage-backed securities crisis of 2008. Cheap homes propped up by federal housing insurance collapsed. Government-run central banks bailed out private banks with billions in newly printed cash. ZHA lost much of its work and had to lay off masses of staffers. This was a turning point for Schumacher, who met Jedlička in subsequent years through a community in the European Union engaged in freewheeling intellectual discussions about libertarianism. He was intrigued by Jedlička and Markovicova’s project of reimagining government according to libertarian ideas.

Jedlička sees the Liberland Metaverse as a way of presenting plans for building its real-world state as well as a way to experience a metaphysical version of the anticipated conditions. In both cases, state planning takes a precedence. “We are trying to build a regular nation in the Balkans,” Jedlička told me, “and we are trying to do our best to put every single stone in place to build a regular nation with a regular country and a regular state apparatus attached to it.” He views the Liberland Metaverse as an entrepreneurial libertarian virtual reality associated with this physical place. In that sense its function sounds more like a traditional architectural rendering, or for that matter, what architectural drawings have always been: sketches of possible futures, which may or may not be realized as buildings.

Over the last few years, however, as Schumacher and ZHA’s research and investment grew deeper, they began to feel that the latent possibility of the metaverse went beyond this role. They are contemplating spinning off their research into a second project, possibly to be named Metatopia. It would have both a physical office, gathering designers from various fields in a shared ecosystem, and a VR-designed metropolis, encompassing the metaverse’s digital functions in one technology platform. “A place like this will be wonderful, and we will have our own checks and balances and moderation policies, and different districts will be self-governing as subsidiary DAOs,” Schumacher said. “This is our overall roadmap. Eventually some of the things which are discovered in this space might feed back into the real world because real world democracy has a lot of problems.”

The function of Liberland Metaverse sounds more like a traditional architectural rendering: sketches of possible futures, which may or may not be realized as buildings.

The team is currently seeking investors and corporate subscribers who would pay fees in the range of 10,000 USD per month to use the metaverse network and cover its server costs. He says the cost reflects the data power required to back it. It sounds an awful lot like real estate in the world we as we already know it. The new demand for energy will be enormous for a system that in many cases does little that a phone call or meeting in a coffee shop can’t.

At the moment, the metaverse remains a fairly inchoate project. It isn’t solving any real-world architectural or economic and political problems, but it also hasn’t caused any real-world harm. Yet the hopes expressed for the emerging metaverse—in Liberland and beyond—are reminiscent of the late 1990s, when it was common to believe that nearly free and universal access to information would have a democratizing effect on the world. As some predicted, this potential to level power imbalances and offer more influence to the general public has been offset in large measure by rent-seeking corporations that govern our online attention as a speculative gambit in search of short-term profits. Now, too, venture capitalists are assembling piles of dollars to capture the metaverse market. Rebranded as Meta, Facebook has obviously bet on remaining a social media monopoly by dominating it. What we need is a Wikipedia-style collaborative framework that would govern based on a common interest in being well-informed. More likely, a new player will emerge out of a Wild West of small, highly capitalized startups. But will they be looking for anything other than a return on investment?

Stephen Zacks is an advocacy journalist and project organizer based in New York City.