Fork Your Society, I want Out

Silicon Valley thought leader Balaji Srinivasan has proposed a revolutionary new form of statecraft, but it’s limited by metaphors of software development.

Last summer, we were having dinner with Shumon Basar when he raised a question: What will the next era of media be? As a prompt, he spouted off a shortlist of recent media eras: mainstream, indie, social, recommendation… At the time, “vibe shift” was trending, crypto was crashing, and Russia’s war in Ukraine raged without reprieve. Fukuyama’s declaration of the “end of history” was once again up for debate.

As we know from media theory à la McLuhan, a shift in the dominant media apparatus alters not just how content circulates, but the kind of content we make, and the types of responses people have to it. When we talk about “generations,” we are speaking about age cohorts differentiated by media eras and how they shaped a sense of reality. TV’s signal galvanized young Boomers around the cultural revolutions of the 1960s. The rise of desktop publishing, consumer-grade music samplers, and home video recorders gave Gen X the hardware for a media environment both democratized and comparatively decentralized. By the ’00s, an internet networked according to IRL friends and self-selected interest groups radicalized Millennials away from top-down media. But horizontal, user-directed social media would soon be disrupted by a protocol capable of algorithmically tailoring information to each user’s individual digital activity. Recommendation media typifies the information sphere of Zoomers.

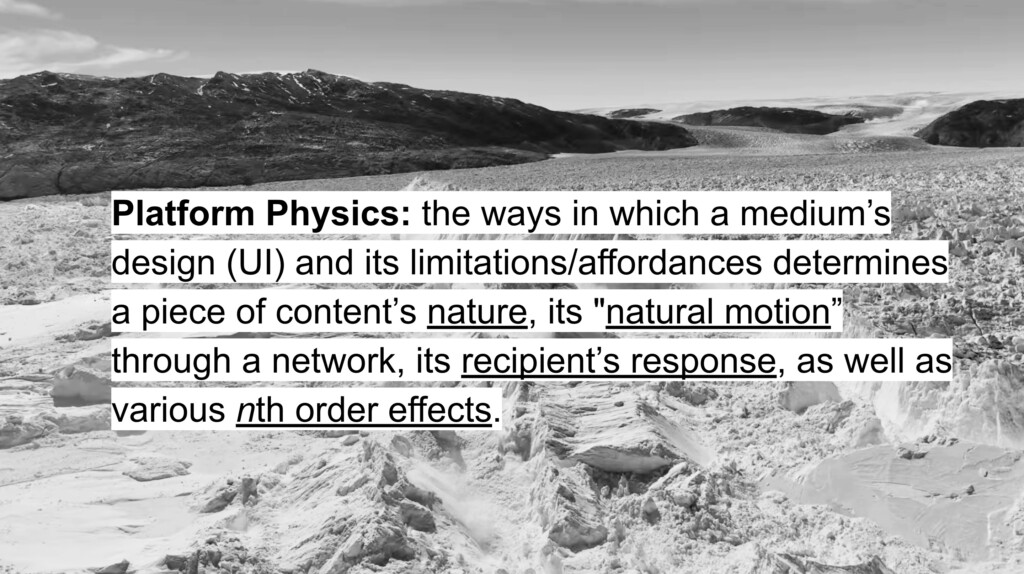

Platform physics are the ways in which a medium’s design determines a piece of content’s nature and its “natural motion” through a network.

Importantly, each era of technology has a unique “physics”—a term we use to describe the hard-coded mechanics and incentives of every media platform, whether digital or analog. Users are as bound to these conditions when operating within a given platform as they are to gravity when walking on Earth. Platform physics are the ways in which a medium’s design determines a piece of content’s nature, the content’s “natural motion” through a network, its recipients’ responses, and the various nth order effects of this content being in circulation.

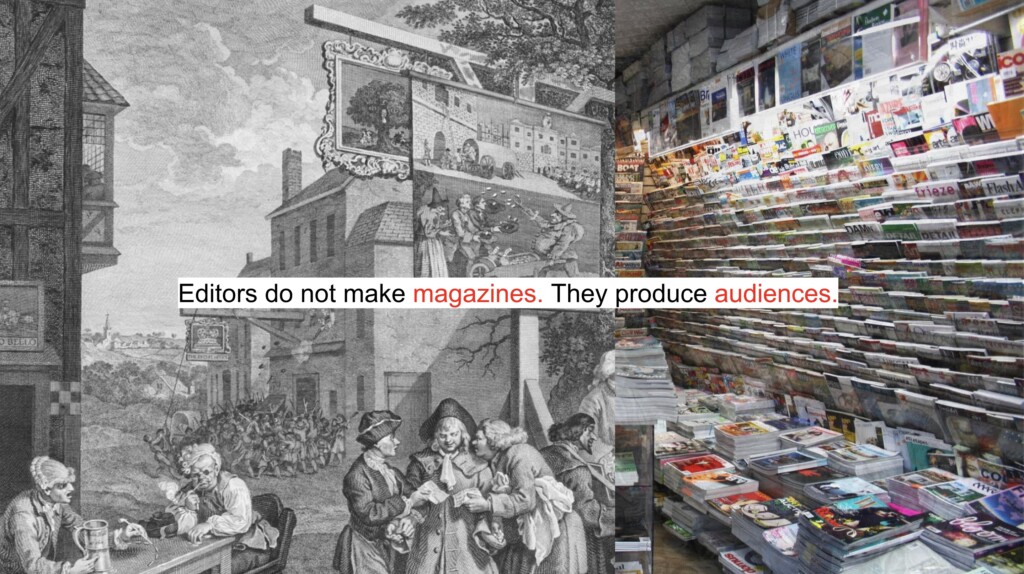

Consider the physics of the monthly art magazine. The format was correlated to the rhythm of gallery shows (also monthly), allowing time for consensus around an artist’s new work to percolate through a scene before the critic’s word influenced the reception. Twitter, by contrast, is built around features such as the retweet that incentivize rapid virality, creating a power law for content where a small first-mover subset attracts outsize attention before more nuanced takes can be formed. The differing physics of these two platforms produce two different kinds of criticism, and arguably, two different kinds of audiences.

A major shift in media protocol in the 2010s compelled the two of us to leave our professional positions in publishing and the music industry. We had spent our twenties learning the rules of one game, but a new one took hold circa 2012, and the existing infrastructure couldn’t absorb the shockwaves. Audiences fragmented. Music labels went broke due to streaming. Longstanding print publications had to go digital-first, often making their content free. In turn, record deals dried up, writers’ fees plummeted, and across the board compensation for culture-sector work was offered in the form of (rapidly devaluing) “exposure.” Critical terrain turned into a virtual swamp of signs and information starved for context, where only the most sensational content wins.

As the media space grew noisier, paths around the mess of algorithmic social media emerged organically in the mid-2010s. As we and others have theorized, this emergent zone external to web2 platforms might be thought of as a “dark forest” or “cozy web” region of media, a semi-anonymous yet paradoxically more personal space of communication: the group exchanges on Discord, Telegram, WhatsApp, Signal, etc.) not indexed by search engines on the clearnet—the publicly accessible internet—and therefore not governed by clearnet physics. (For more on this, see Yancey Strickler’s “The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet,” Maggie Appleton’s “The Dark Forest and the Cozy Web, ”Venkatesh Rao’s “The Extended Internet Universe,” Peter Limberg’s “Clearnet, Dark Forest, Darknet” and Caroline Busta on contemporary counterculture.)

Those spending time in dark forest spaces often continue to use Web 2.0 platforms. But while most of us probably still check the main feeds daily to get a current pulse, they are no longer our primary sites of communication. Nor are they the sites of identity formation that they once were. Feeds have become something like interstate roadways with posts as billboards—fleeting pieces of information that momentarily make us laugh or annoyed, and that occasionally compel us to exit.

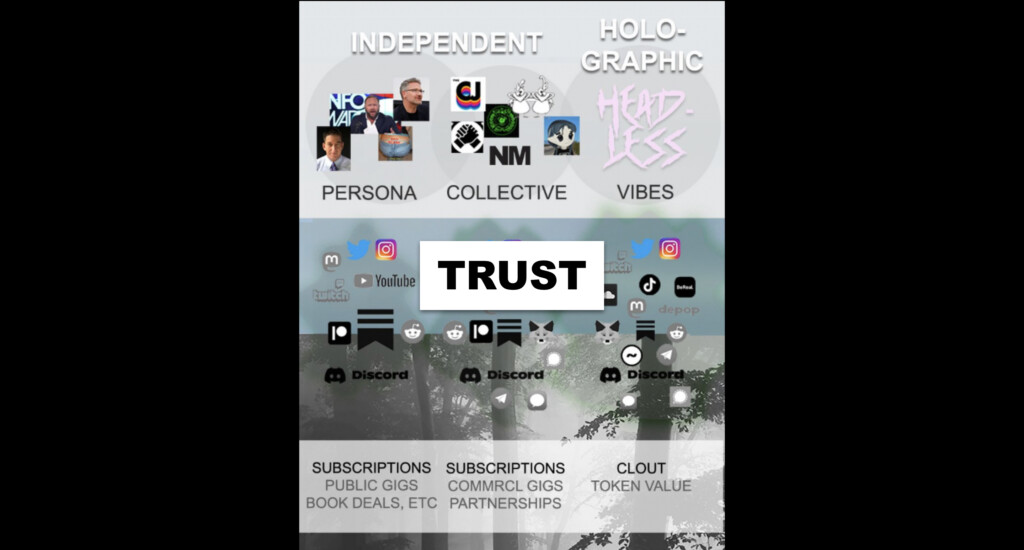

Present-day media should be taxonomized not by format or scale or genre but by how well they compose their own media ecosystem—how nimbly an outlet can work across various platforms and protocols, from clearnet to dark forest. Noting the importance of this skill, political scientist Kevin Munger said: “If you and your community do not have a concrete set of norms, practices and institutions designed to allow you to use the internet without the internet using you—you are destined to lose. In fact, you’re not even trying to win.” The more varied an outlet’s spread of platforms, the less beholden it is to any single one. The less bound it is by any one platform’s physics.

Present-day media should be taxonomized not by format or scale or genre but by how well they compose their own media ecosystem.

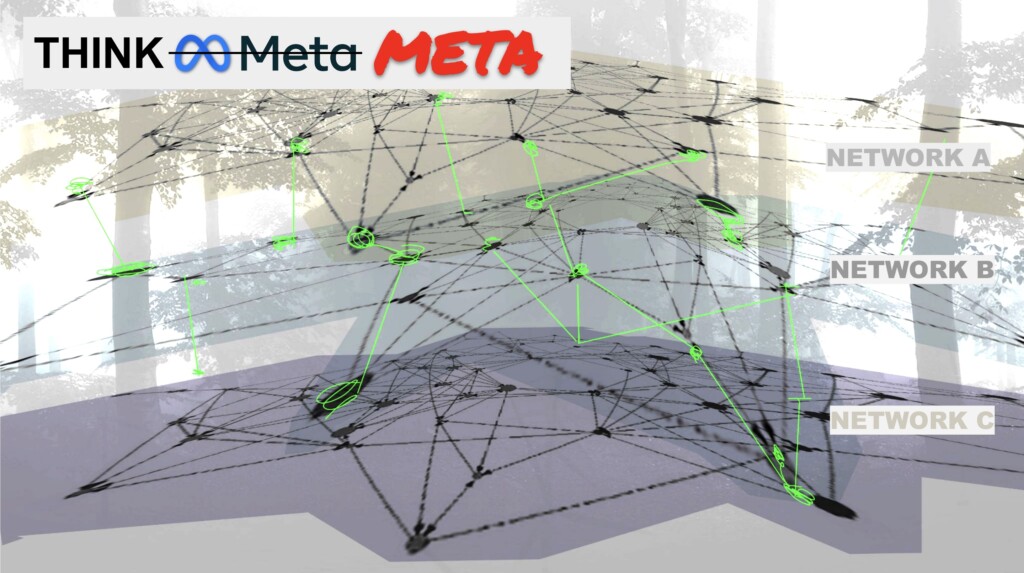

Essentially, the capacity for composability emerges as an indispensable quality of our current mediascape. Composability is already a popular concept in crypto circles, where it refers to building “protocols” rather than platforms, and portability of a community across platforms through token-based social graphs. But we see it extending beyond web3 systems. Already in the mid-2010s, dark-forest groups had devised ways of finding each other across constellations of platforms (whether by including key emojis in one’s bio—a pine tree, a frog, a black fist, a rainbow flag—or through sharing content from certain meme pages so members of an enclave can synch their clearnet feeds). Structurally, what these communities were doing was composing their own media networks. They were forging a social protocol where the community signal is stronger than the pull of any individual platform. We might even say that the community itself becomes a form of media, a holographic filter through which every platform is accessed and where individuals with strong connections across multiple communities become literal inter-faces for information.

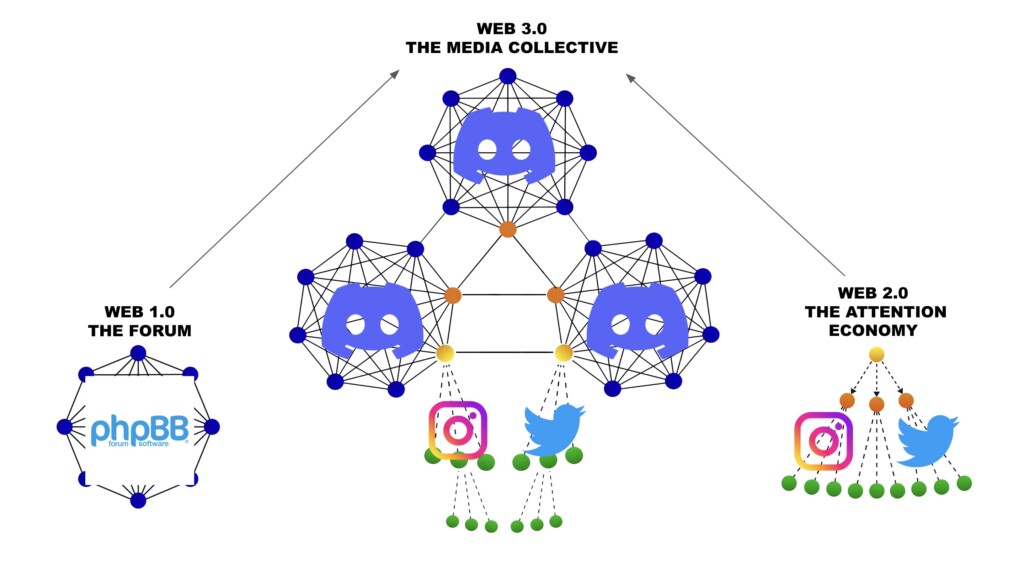

To understand what this new era of community as media looks like, imagine the Web 1.0 webforum—multiple nodes arranged in a circle, each equally connected to the others. Now imagine the Web 2.0 attention-driven network: a sea of individual influencers connected unidirectionally to tiers of followers. In a composable community-as-media model, a protocol synthesizes both. Members of a shared network interact in a non-gamified, horizontal way—as in webforums—while also broadcasting across social media feeds, cross-pollinating their community’s thoughts and attracting new members.

With this new media schematic in mind, let’s now speculate on some of the phenomena this media era may produce.

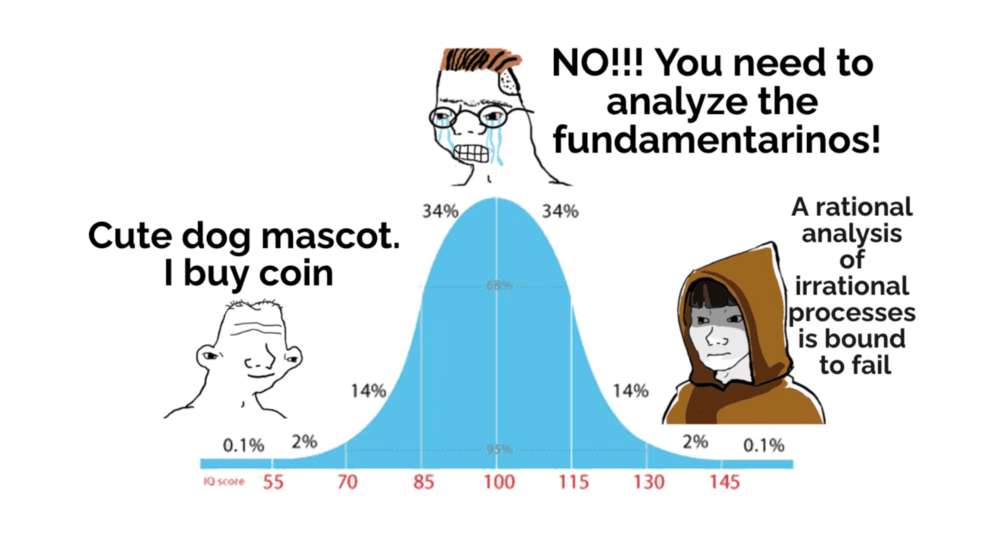

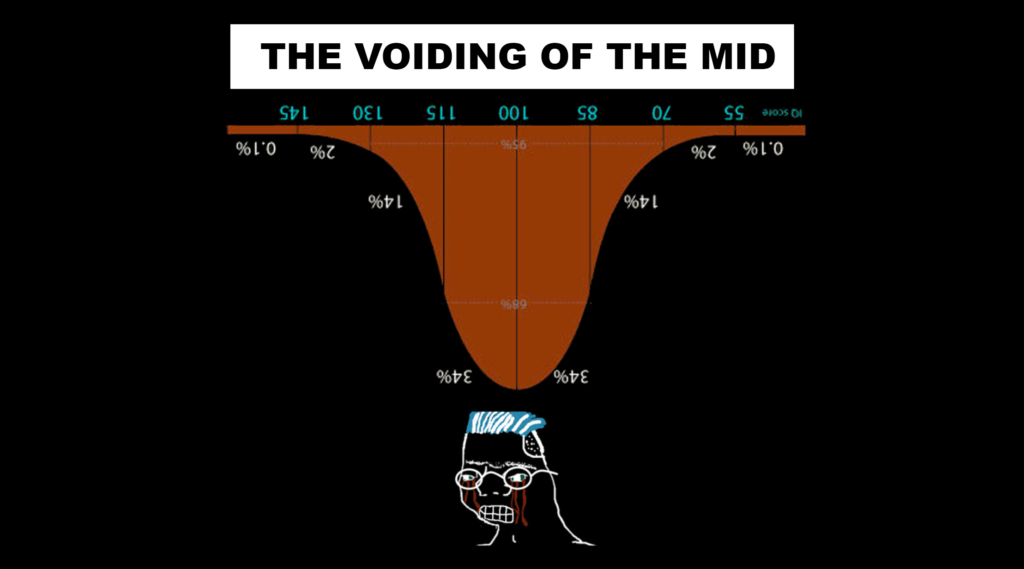

In The Extreme Self (2021), Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke of the “100ocracy”—the power of the middle of the bell curve—making the point that online, scale always wins and therefore the average is king. But this principle doesn’t only apply to entertainment, retail products, and narrative production; it equally applies to exploits and scams. This is why a Windows computer or Android phone is far more likely to get a virus. There are simply more Windows and Android users and so bad actors have more opportunities for success by targeting these operating systems rather than others. The optimal place to be is on the left or the right of the curve.

As cybercrime explodes and AI-enabled bots multiply the already dominant average, we anticipate a voiding of the Mid, especially on social media. Younger generations are already suffering from Mid-exhaustion as endless culture-warring and grandstanding didacticism have made “👏using 👏your👏voice” on social media seem extremely cringe. And if you think the spam and scams are already bad, just wait. The first AI to achieve sentience could very well be a Men’s Rights Activist who earned a fortune emptying the bank accounts of high-net-worth individuals by emulating their voices.

Illegibility. Poetry. Speaking even more in diagrams, images, metaphors, collages, neologisms—forms of language that AI (and the Mids) do not yet understand. These are tools for avoiding the Mid-void. Another strategy? Bringing back the sanctitude of True Names. When something’s or someone’s True Name is known, it can be exploited for attention and other economies. Giving a True Name allows for indexing, search engine optimization, and for that thing or person to be consumed by the Mid. Dark-forest spaces allow True Names to be better protected, or kept hidden entirely.

Beyond the voided Mid, dark forests will proliferate. In the digital and in the real, we need to plant more trees. Everyone will belong to one or more of these dark forest communities, and will need to defend their culture from spammers and scammers from the Mid.

Scamming on a societal scale has been a constant in the world for those who have grown up in the twenty-first century. The late-’90s dot-com bubble? The result of a now-classic scam where internet companies receive a ridiculously high valuation because, theoretically, the total addressable market is every single person who can access the internet. That bubble quickly popped but it’s a great scam and we love it. We still do it today! In the early ’00s, George W. Bush gaslit the West into believing the Iraqis did 9/11. Then the Obama administration convinced 70 percent of Americans that the Islamic State was “the number one threat to American interests.” Defense contracting go brrrr. The financial crisis of 2007 –08 rounded out the decade, and its reverberations continue to destabilize the global economy. Crypto is a scam, too, and everyone knows it. OK, blockchain is not inherently a scam, but the scam potential in recent years was just too big to not scam. Uniquely, crypto created a massive, social media-based scam, with hundreds of thousands of people actively evangelizing ideas they believed only because there was a monetary incentive to do so. Crypto’s True Name, however, was spelled out in the rubble of the FTX collapse, and now, hopefully, its scamming has passed its peak. In America, virtually every ad on TV is for pharmaceuticals or sports betting. Apps are engineered to be maximally addictive, siphoning as much time and money as they can from “users.” Young people are fully immersed in an addiction economy—it’s all one big scam, and they know it. Scam Realism is the paradigm of the now, because scamming is the water in which we all swim, even if we twentieth-century dinosaurs try to not admit it.

When there’s so much noise and so much scamming, where do we find truth and who can we trust? Overwhelmed by the sheer volume of conflicting information, hot takes, scoldcore, and didactic thinkpieces from the Professional Managerial Class, people increasingly trust only those to whom they’re directly connected—whether personally, or parasocially. And this is why non-institutional figures—Substack writers, artists, podcasters—and their wider communities will continue to fulfill the role of Trusted Sensemakers. Meanwhile, corporations and governments will need to cultivate relationships with these sensemakers in order to gain broader trust—and traction.

And so, smart twenty-first-century natives think meta. They think the way our Tech Overlords think. Why build products or services, when you can control and therefore capitalize on the infrastructure through which every exchange takes place?

To gain agency in today’s media space, you need to overcome the physics of its software. By thinking meta, you can build new protocols, structures that allow truth and trust to emerge. Whether through blockchain tools, new nested internets, or meta-assemblages of various platforms and apps, the future of media will come from experiments taking place at the level of protocol. And through these new protocols, new complexities will emerge through new relationships—complexities that we should embrace. Worldbuilding together, we can keep True Names secret, protected from the homogenizing force of the Mid, allowing for a return of productive incoherence, uncertainty, deep wisdom, and magic.

This essay is adapted from a presentation delivered at Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum on March 4, 2023, titled “Understanding Predicting Media.” Images are reproduced from the accompanying slideshow.

Caroline Busta and Lil Internet are co-founders of New Models, a Berlin-based media channel and community.