The Hirsch Truth: Episode 1

A video critique of PFP projects World of Women and Milady Maker, plus works by Katherine Frazier and Sara Ludy.

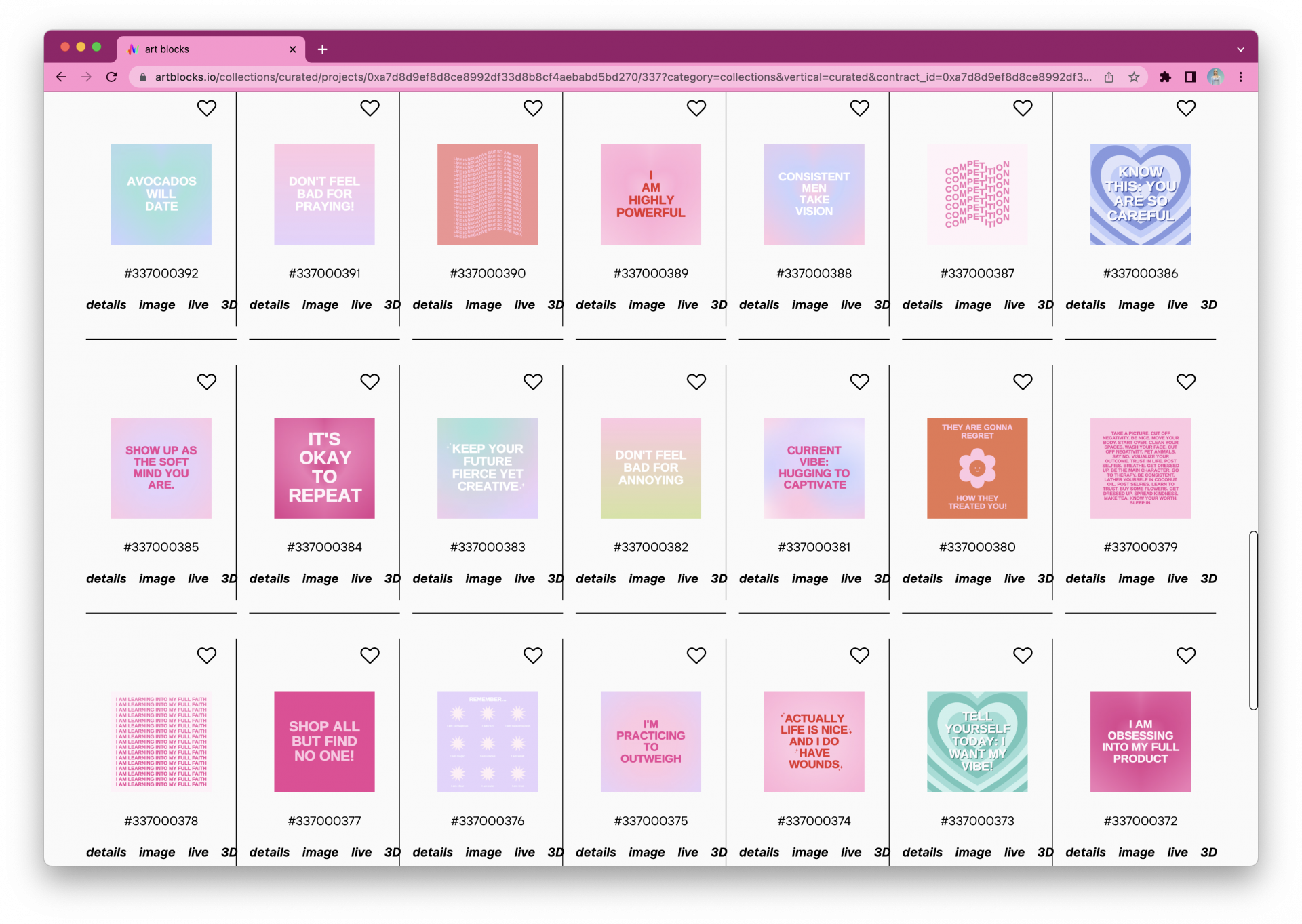

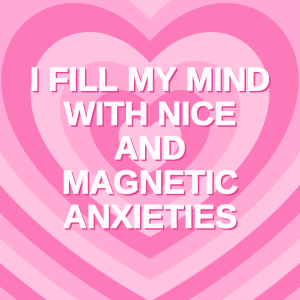

Maya Man’s NFT series Fake It Till You Make It (FITYMI), released on the blockchain-based generative art platform Art Blocks last month, explores the language and aesthetics of online self-care and wellness communities—specifically, the proliferation of girlishly colored memes with encouraging mantras about self-love and mental health. Man’s source material will be intimately familiar to her fellow millennial and Gen Z women; these authoritative pastel squares gained traction during the Trump administration, as women leaned into self-care as activism in the face of a relentless news cycle and a politically chaotic world.

Wellness memes gained traction during the Trump administration, as women leaned into self-care as activism in the face of a relentless news cycle and a politically chaotic world.

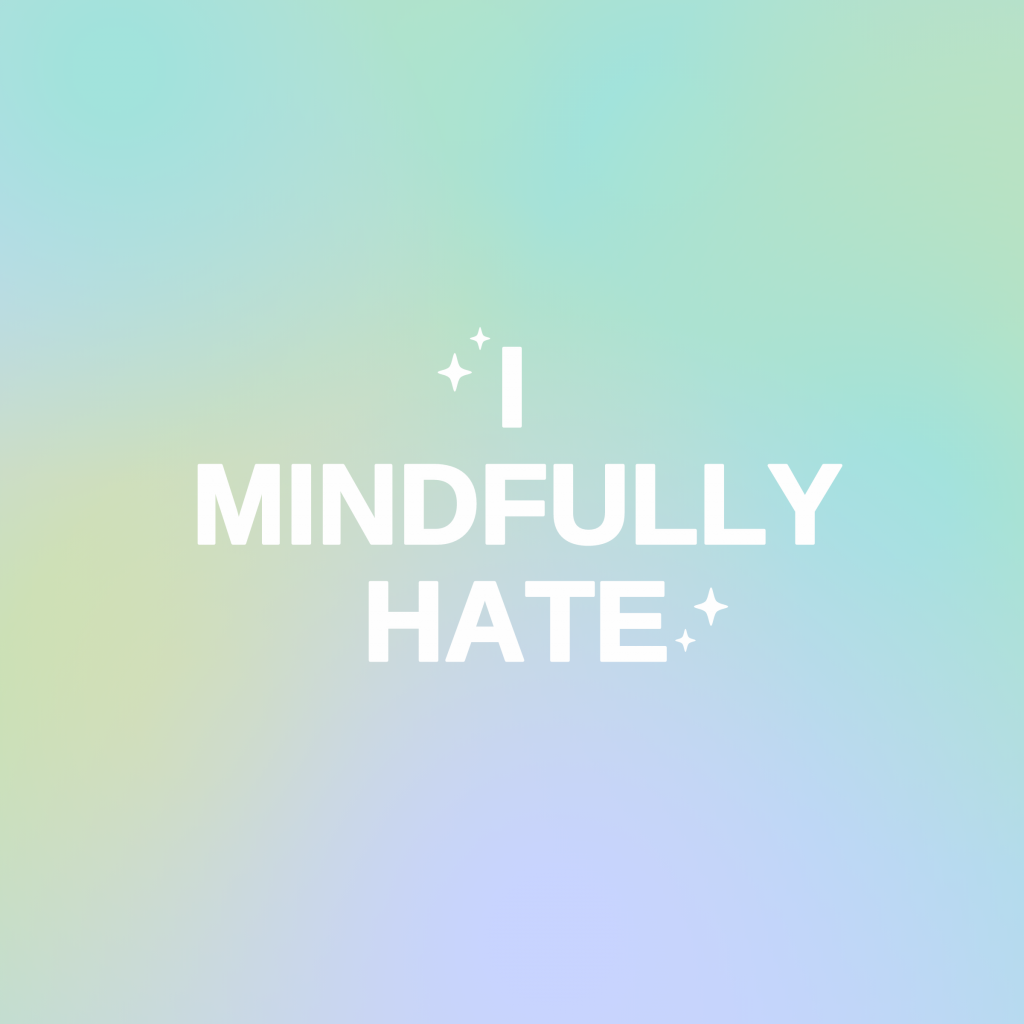

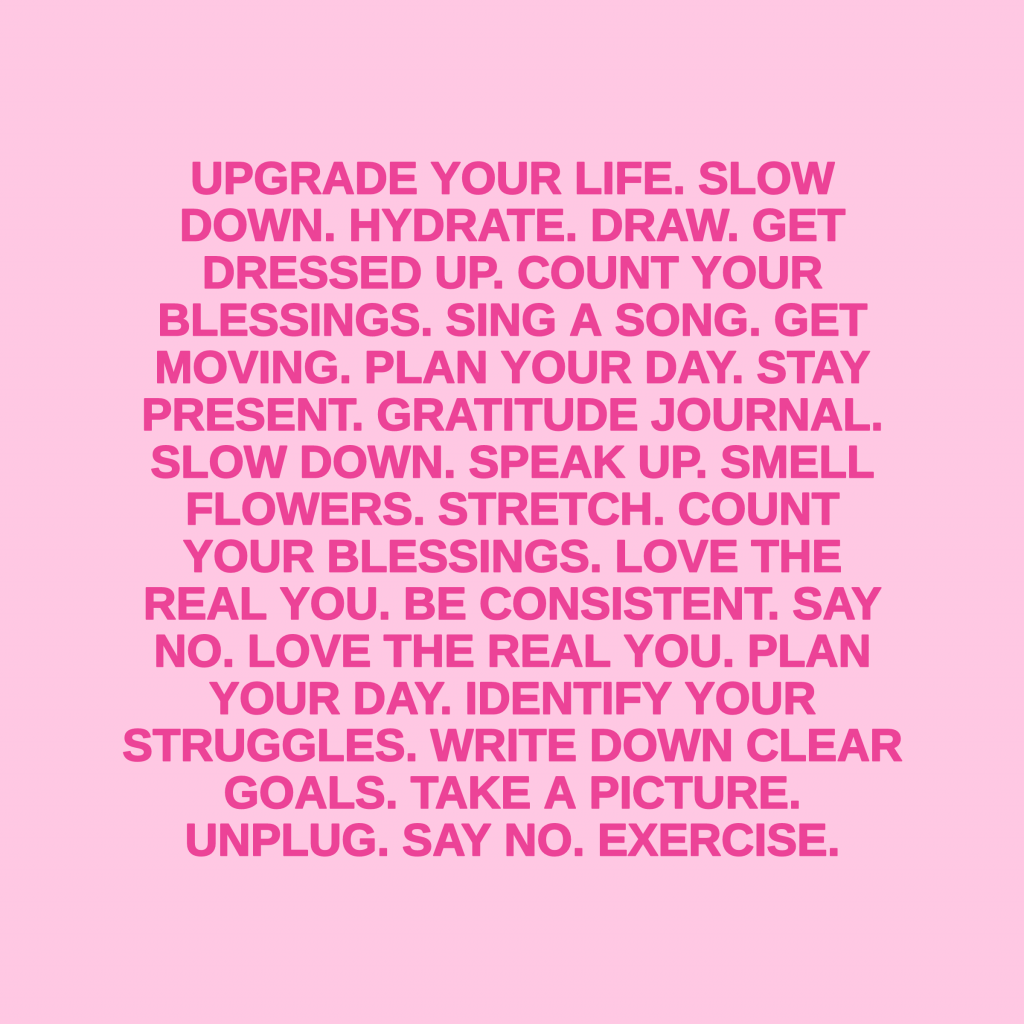

To create FITYMI, Man trained an algorithm on empowerment-core Instagram design conventions and language sourced from popular accounts in this genre. The result is a series of seven hundred NFTs in saccharine shades with slogans that range from earnest (YOU LOOK BEAUTIFUL TODAY) to silly (CURRENT MOOD: CRYING THROUGH BUSINESS) to sinister (YOUR REALITY IS LYING TO THE WORLD). By coaxing a machine to generate wellness memes, Man highlights the formulaic and often unwittingly absurd nature of this content and its tendency to flatten complex human experiences into easily digestible platitudes—and how even these can elicit strong emotional reactions.

While the project was born from Man’s initial suspicion of these digital mantras, she insists that her intent is not to mock their wisdom, but rather to encourage critical engagement. “I started the project feeling cynical about them, but as I generated more and more of the graphics, I started to find some that were honestly kind of deep,” Man said in an interview. “I definitely follow and am swayed by wellness culture. I wanted to think about what it means for someone to see, like, comment and post these graphics, and to examine how these belief systems proliferate on a network like Instagram.”

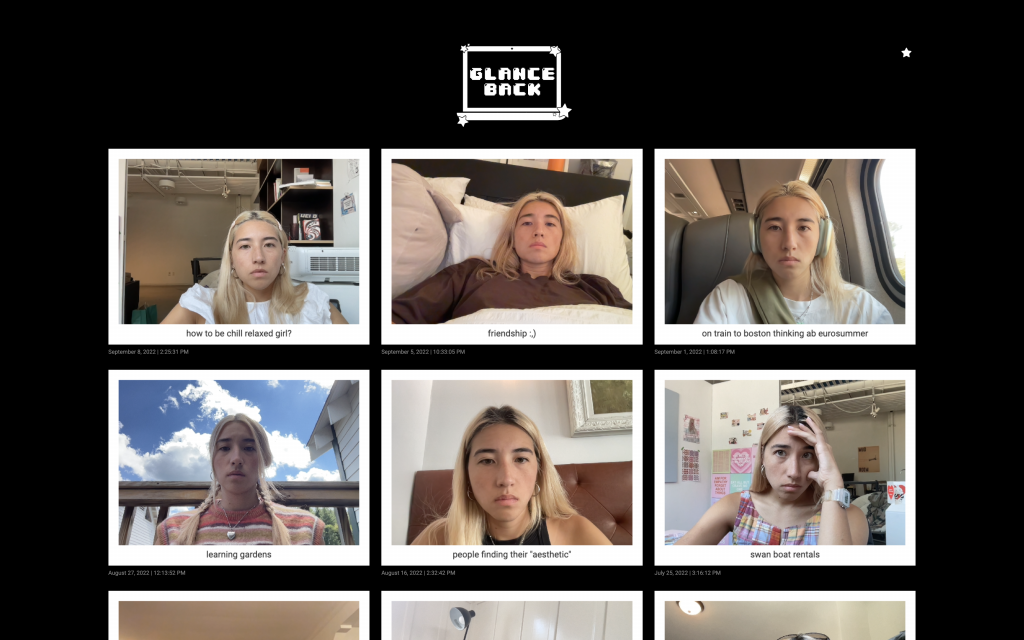

FITYMI builds on Man’s ongoing artistic explorations of the performance and commodification of the self that is part of being a girl on the internet today. Her app Glance Back, released in 2019, captures spontaneous, intimate moments between users and their computer screens and compiles them into digital photo diaries. For her exhibition “Secrets From a Girl,” which debuted at UCLA this past spring and then traveled to Soot Gallery in Tokyo, Man transformed a gallery into a childhood bedroom—the site where girls learn to “be themselves” online—and featured generative work that remixed her personal diaries and social media outputs with gender theory texts and teen girl magazines like Seventeen. The exhibition also included iterations of the FITYMI script, projected onto square canvases, with selected outputs printed on canvas.

Online, Man does not shy away from performing femininity; her Instagram and TikTok feeds showcase fit pics, cutesy selfies, and pouty-faced dance videos alongside more formal artworks. This artist-as-influencer aesthetic brings to mind other young female artists such as painter Chloe Wise and zine maker Jo Rosenthal—modern day Carrie Bradshaws whose online personas and covetable style have spawned brand collaborations, modeling opportunities, and parasocial relationships with fans. It’s tempting to dismiss the likes of Wise and Rosenthal as influencers first, artists second. But that would be to overlook the creative talent necessary to effectively perform as an authentic yet aspirational female artist online. Man herself is not only performing this role, but also making art that embraces the complexity of that process, including accompanying feelings of confusion, shame, and anxiety. “In high school I felt very confused about my identity and how to perform on these platforms that have rigid rules and etiquette about what and how you should post. I always felt guilty that I was somehow being fake by posting online,” she said. “It was really freeing for me to start thinking about posting solely as a performance and to acknowledge that’s what we’re all doing.” By transmitting her art and life online in this way, Man can reach audiences beyond typical gallery attendees. Unsurprisingly, many of her fans are other young women who enjoy seeing their own conflicting feelings about life on the internet reflected back with a critical, thoughtful eye.

FITYMI was included in Art Blocks’ Curated Collection, which presents work selected by the platform’s board of experts. Like most of these projects, FITYMI sold out soon after its release. But FITYMI’s hyperfeminine look, text-based format and conceptual nature are notably different from the muted color palettes and geometric compositions that dominate the Curated Collection. Since her release, Man has enjoyed watching FITYMI collectors change their Discord profile pictures to “girlie little hearts with soft colors.”

On the FITYMI website, which features an aptly playful .lol domain, Man ponders the social performance inherent in sharing wellness memes: “Online, these types of posts survive on likes, comments, and shares. What do I believe? becomes What do I want to appear to believe?” In the current climate, this statement perhaps more pertinently applies to the spread of social justice infographics that reduce complex political issues to simple square images, reposted as evidence of “doing the work.” On Instagram, these graphics proliferated at a fever pitch during the 2020 protests against racism and police brutality. Now they are a mainstay. The artist Brad Troemel, a master of the satirical infographic, explained the moral imperative to share this content in an Instagram post: “What’s so ingenious about infographics is the way they offer moral salvation, not just to those who read them, but specifically to those who share the good word… If we follow the logic of the infographic just a step beyond the idea that you’re a good person for sharing a post, then it naturally follows that everyone who doesn’t share that post is a bad person.” A boom in social justice infographics has coincided with the diminished cultural relevance of the wellness memes that FITYMI interrogates, reflecting a theoretical, if not material, turn away from individual self-care as liberation. Today, the average left-leaning Instagram user is more likely to strive to present as an engaged supporter of both Palestinian resistance and her working-class neighbors than as a yogini with a robust personal mantra practice, as wellness memes imply.

Unsurprisingly, many of her fans are other young women who enjoy seeing their own conflicting feelings about life on the internet reflected back with a critical, thoughtful eye.

Man cites Amanda Montell’s Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism (2021) as an inspiration for FITYMI. Among other things, the book charts the relationship between the Protestant work ethic, the language of the self-help industry, and American identity. “This new mind-over-matter attitude that you could control your own destiny, that you could govern everything from your career to your physical health just by believing in yourself, contributed to what we now think of as the American dream,” Montell writes. While the self-care industrial complex may be fading from the Instagram discourse, the insidious promotion of constant striving towards self-actualization—a state that remains perpetually just out of reach—will inevitably shapeshift and present in new and similarly performative forms. In this way, Man’s FITYMI reflects both a specific moment in girl culture and the enduring conflict of the American psyche.

Tara Kenny is a culture writer based in New York.