The Artist is Online

The history of digital performance shows how the obligation to maintain a personal brand online can offer space for experimentation.

In 1998, from her home in New York, Auriea Harvey decided to “go live.” With a T1 line and some bespoke software, she set up a camera that, every few seconds, streamed black-and-white photos of her working at her computer to her website. People from around the world watched her at her machine while sitting in front of their own. At the time, Harvey was not only an active net artist, but also working in desktop publishing and web design. By broadcasting these “behind-the-scenes” images, Harvey played with the notion of a networked panopticon, surrendering her privacy and rendering her labor visible in exchange for an online audience’s attention. How strange it was, at the time, to so easily access an artist’s current state of being. Now such access is commonplace. The contemporary digital art ecosystem demands a steady stream of online content to maintain relevance in the eyes of the public. Harvey’s landmark “streaming” project anticipated the mechanisms of the current creative economy for digital artists, which rewards performances of labor that are visible, legible, and a quick click away.

The contemporary digital art ecosystem demands a steady stream of online content to maintain relevance.

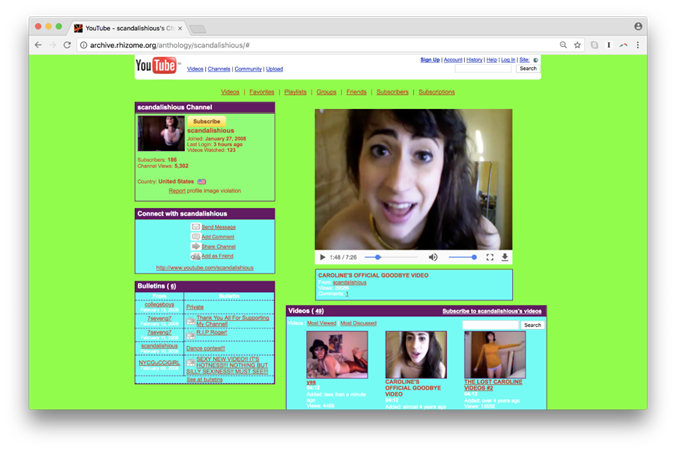

In the decades following Harvey’s prescient piece, artists have played with ideas of self-presentation and surveillance on emerging social media platforms. For her piece Scandalishious (2008), staged on YouTube, Ann Hirsch performed as Caroline, a young girl who dances and chats to the camera. Over time this performance amassed a captivated and perplexed audience of thousands on YouTube, subverting expectations of how a girl might perform on the nascent platform. Hirsch intentionally confuses the boundary between our “real-life” selves, our fantasy selves, and how the two intertwine online and off. Molly Soda’s Inbox Full (2013) is an eight-hour endurance performance of her reading every message she had received from other users on Tumblr, a platform she was uploading content to regularly. The messages she reads range from admonishing to admiring. By speaking these out loud for her webcam, Soda employs herself as a vehicle to expose the usually private perspective of the audience, emphasizing their constant presence online despite their invisibility. For Social Turkers (2013), Lauren Lee McCarthy paid remote workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to watch her go on OkCupid dates, interpret what was happening, and direct her on what to do or say next. She released control over her love life to strangers on the internet, allowing them to judge and dictate her actions while engaging potential new partners.

Each of these works gained ample attention not only from art-engaged communities, but also from broader online publics. Interfering in the endless feedback loop between the persona of the artist and the product of their practice, they intentionally confuse the identity of the artist and the artwork itself. The asynchronicity of social media forces us to watch ourselves. Logging on, we are confronted with versions of us that we have broadcast in bits and pieces of imagery, video, and quippy snippets of text. As social media platforms began infiltrating into our everyday lives in the late 2000s to mid-2010s, these artists pushed things one step further, forcing an audience to watch them watch themselves.

Can an artist’s performance ever truly end on the internet? In his 2014 essay “Athletic Aesthetics,” Brad Troemel highlights the mounting pressure on artists to output media at a hyper-active pace by drawing an analogy to athletes. “Athletic aesthetics are a by-product of art’s new mediated environment, wherein creators must compete for online attention in the midst of an overwhelming amount of information,” Troemel writes. “Artists using social media have transformed the notion of a ‘work’ from a series of isolated projects to a constant broadcast of one’s artistic identity as a recognizable, unique brand.” In their work, Harvey, Hirsch, Soda, and McCarthy have each independently posed a similar provocation: the artist as an increasingly internet-entangled worker. Artists of all kinds have long dealt with the two crucial layers of labor endemic to their profession: First, the making of the artwork itself, and second, its promotion. But progressively, the persona of the artist, as it can now be freely communicated via social media platforms, has nudged its way into the equation. Digital artists feel this especially intensely. Those who are making work on and about internet are using their personal social media profiles as a vehicle for sharing and promotion. If the medium is the message, the “new media” most artists are experimenting with today is the online presentation of self.

Can an artist’s performance ever truly end on the internet?

And so, the borders between “artist” and “influencer” are blurring. The explicit job description of influencers involves laboring online with an independent entrepreneurial strategy. Though “artist” connotes a more romantic role, in practice artists are now encouraged to do the same. As Sophie Bishop wrote in 2022, no artist now can escape from “influencer creep,” which she describes as “the on-edge feeling that you have not done enough for social media platforms: that you can be more on trend, more authentic, more responsive—always more.” With few opportunities to show their work in galleries or institutions, digital artists are obliged to use their personal social media profiles as a stage for exhibition, posting content that ultimately contributes to a cohesive, online representation of their practice—in other words, a personal brand. Digital artists who are sharing their work on the internet are now forced to embody the qualities of a marketing manager, working to maximize visibility in an oversaturated media landscape.

Already, the chaos of this cultural climate had the digital art community buzzing. But then came a new, dramatic disruption. Enter NFTs. Their introduction birthed a new market for artists who make digital, file-based work. Initial hopefuls claimed web3 would bring freedom from the outdated structures of the Web 2.0 and traditional art world. When artists take responsibility for both producing and promoting major bodies of work, they gain an unprecedented level of autonomy. But rather than fighting the rise of corporate LARPing as a necessary imposition on digital artists, this outlook doubles down on the ideas surrounding the artist’s self as “brand.” Full online autonomy forces artists to sacrifice the checks and balances of a system like that of the traditional gallery, which is designed to distribute the labor of contextualizing and communicating an artist’s practice.

If the medium is the message, the “new media” most artists are experimenting with today is the online presentation of self.

Like influencers who are encouraged to post two to three times a day on TikTok to increase visibility, digital artists releasing work as NFTs are often encouraged to produce context-as-content around their work at a laborious pace. Many of these artists are burning out, shouting into the whirlpool of the X “For You” feed. If they don’t, who will? In an always-on environment, how should contemporary software and internet-based artists “perform” their work and labor on social media? What does an artwork, a complex opinion, or a “space” look like when it’s not forced to be sandwiched between an internet thinkboi one-liner and the Pop Crave post of a celebrity who “stuns in new photo”? How might we reconcile with the structures of centralized selfhood that a distributed, internet-based art circuit encourages?

The utopian ideal of artistic independence on the internet currently translates to a constant stream of self-producing labor reminiscent of Harvey’s Webcam Movies. Pioneering net artists such as Harvey, Hirsch, Soda, and McCarthy captured the uncanniness of the imposed “always on” state of durational performance online. Can we learn from the way in which these artists embraced performance in their online presence and employ influencer behavior in a way that threatens dominant structures? Artists currently have the chance to play choreographer in relationship to the online stage. They decide which portions of their practice they dish out and make legible, illegible, or culturally exclusive—only legible to certain groups. Mass attention may dictate who rises according to narrow definitions of success, but micro attention might become a stronger guiding force for artists who want to build something steadier and more sustained. Micro-influencers, with the satisfaction of that prefix, may be on to something indeed. Previously, there was a reckoning in fashion with the rise of bloggers, in music with the rise of TikTok, in publishing with the rise of online magazines. The landscape of internet-born art is currently reckoning with the traditional structures of the art world. Against this backdrop, can posting online be reframed not as an auxiliary act, but instead as an experimental medium for artists in itself?

Can posting be reframed not as an auxiliary act, but as an experimental medium in itself?

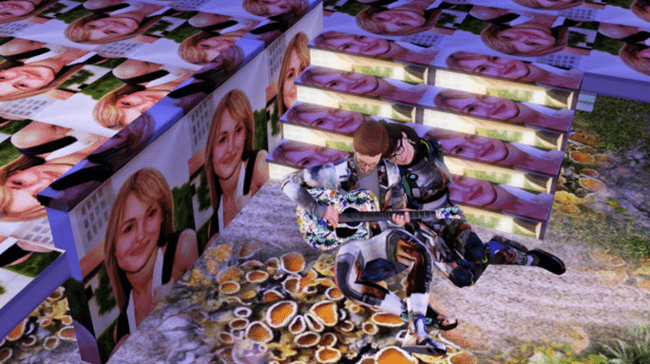

I look to emerging internet artists who post. Honor Levy, whose series of eerie, collaged, chaos-maxxed TikTok videos, all made on her phone, reflect the absurdity of the content stream on the app’s “For You” feed without pandering to its reward functions. On Instagram, anonymous artist Twee Whistler blurs reality with fan fiction (primarily centered around artist Jon Rafman), posting their work as images, videos, and memes. They swirl together critical theory in “slide” style posts alongside documentation of their visual work to produce a subversive profile that requires digging through its layers in order to be fully understood. Like method actors, these artists are inseparable from their online identity and medium. Posting exists as a primary form of exercising their practice. They understand that one fighting way forward is aggressively through.

Tired of reaching up, many artists now are reaching out. I am, too. I find comfort holding onto works by every artist mentioned here. Together, they create a network that reminds me that others share my deepest obsessions and that I am not posting alone. If the curtain never closes on the social media stage, artists must abandon the script. Improvise, press “post,” feel repulsed, delete the app, redownload, and try again. “Took a break from social media, but now I’m back!” It is the performance of a lifetime. The show must go on, but I believe that artists can steal it and make it their own. As they have continued to do, time and time again, online.

Maya Man is an artist based in New York.