The First Hundred Days

A letter from the editor on the challenges and rewards of publishing art criticism in the NFT space

I’ve been texting one person “good night” every night since 2021, in a performance that will continue for the rest of my life. It’s the first in a series of “rest of life” performances that I plan to complete before I die. When I mention my Good Night performance to people, they often remark about my level of commitment. But I don’t necessarily see it that way. I could be dead next week.

I am interested in endurance, though. As technology manipulates time and space, we are pushed to perform new postures and relationships. Performance artists working with the body offer ways of considering care and intimacy in this process.

As technology manipulates time and space, we are pushed to perform new postures and relationships.

I frequently think about Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano’s Art/Life One Year Performance 1983–84, where they spent a year attached by an eight-foot rope around their waists. Now we’re all always connected, always on. Did we have a choice? Do we have the endurance to exist in this state? What commitments do we feel toward one another?

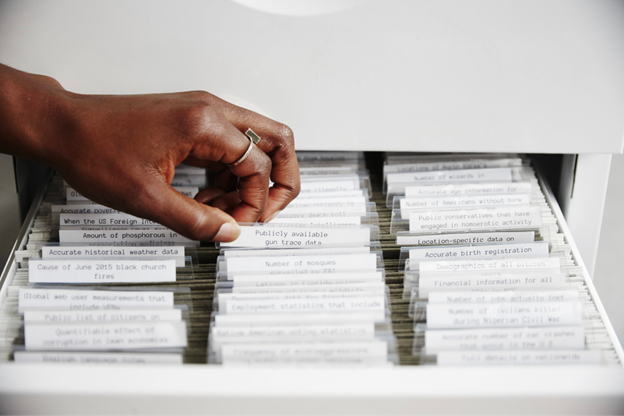

Over the last few years, NFT creators have deployed a series of smart contracts that propose we trust in technology rather than humans. But the technology was made by humans, infused with all the biases and beliefs that get packaged into “neutral” systems. Mimi Ọnụọha’s The Library of Missing Datasets (2016) offers examples of missing datasets, where certain information has been conspicuously uncollected, pointing to hidden biases that inform the technology we’re building to support a world that ignores these data points, or people.

Mary Maggic subverts this existing data landscape by creating their own systems of knowledge according to a logic that is queer, DIY, and open-source. Noting that existing medical data reinforces gender assigned by doctors over gender identity, Maggic built a 3D-scanning tool to crowdsource a database of genital scans, which were then tagged with each person’s self-identified gender. The project, called Genital( * )Panic (2022), manifests as a series of public gynecological workshops and installations, challenging the normative ways data gathering and scientific knowledge are typically performed.

Maggic and I were recently invited by Stanford University to perform together. My performance was part of the series Saliva (2023–), where participants identify a partner for saliva exchange, negotiate the terms of this exchange, and then spit in tubes that they give to each other. Although both Saliva and Maggic’s genital scanning workshop incorporate practices of consent, privacy, and care, the institution shut them down for reasons of liability and general discomfort by administrators. We were asked to shift to a simulation instead.

As digital art is neatly organized into boxes within boxes, performance offers a way to escape the frame.

It’s interesting to contrast this pushback against queer bodies with another project, Lauren (2017–), in which I perform feminized labor as a human equivalent of Amazon Alexa, remotely watching and controlling people’s homes. In this work, there are questions of data privacy that also present risk, but I’ve received little questioning or oversight as I’ve been invited to perform this work. Is it because I am performing an acceptable gender role, or simply because the technology companies have by now desensitized us to any digital breach of privacy and intimacy?

The hacking that occurs in Lauren is consensual. The participant opens their home to me out of trust. I design the Lauren software as an alternative to the predatory, dark data patterns we encounter in our daily technology. But the lines of power become blurry as I control their home and the participant controls me: Lauren, turn on the shower.

We seem to expect a sterile cleanliness from technology. As digital art is neatly organized into boxes within boxes, performance offers a way to escape the frame. Rather than being forced into an auto-suggested submission of convenience, SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY’s SUB NOT SLAVE (2017) proposes submission as an active gesture one can choose to offer in an exchange of power. It is not assumed, taken, or owed. The installation physically and conceptually positions the viewer as sub, interrogating their understanding of dirtiness: What do you think is dirty? What turns you on?

In this messiness there’s an opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of existing on the internet.

In this messiness there’s an opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of existing on the internet. We put our lives and our trust into a vulnerable system where we are repeatedly hacked. Attention is manipulated, passwords are stolen, wallets are emptied, private information is strewn in public. I’m interested in the ways we respond. When women’s rights activist Lena Chen had nude photos of her shared online in one of the earliest cases of revenge porn and cyberstalking, she responded with Elle Peril (2012–17), five years spent posing as a nude model to reclaim agency over her body and personal narrative.

This gesture of reimagining—exploiting the way fact and fiction blur on the internet—is also present in Ann Hirsch’s Playground (2014), where she restaged a relationship she had with a 27-year-old man whom she met on AOL as a preteen in the ’90s. Watching Hirsch’s performance play out through instant messages, I was not directed what to think; I was instead allowed to freely navigate the murky territory. The unease of this work is echoed in Hirsch’s more recent Sacra Familia (2023), which uses AI to create a haunted house of family photos. Both works have the winking feeling of playing user, allowing yourself to be autocompleted, daring to click accept with little understanding of the terms.

For me, each of these performance practices tease a desire for embodied connection amid interfaces. It is the same kind of desire that drove me to perform Sleepover (2020) outside people’s homes throughout the pandemic lockdowns. Lying somewhere between safety, control, and fear, I would spend the night out on their lawn with only text communication between us. Each of us imagining the other’s physicality, a virtual shared presence. Are you still awake? Are you still there? Good night.

Lauren Lee McCarthy is an artist examining social relationships in the midst of automation, surveillance, and algorithmic living.