Pablo Rodriguez-Fraile

A major NFT collector shares his passion for digital art and his reasons for founding the marketplace Aorist.

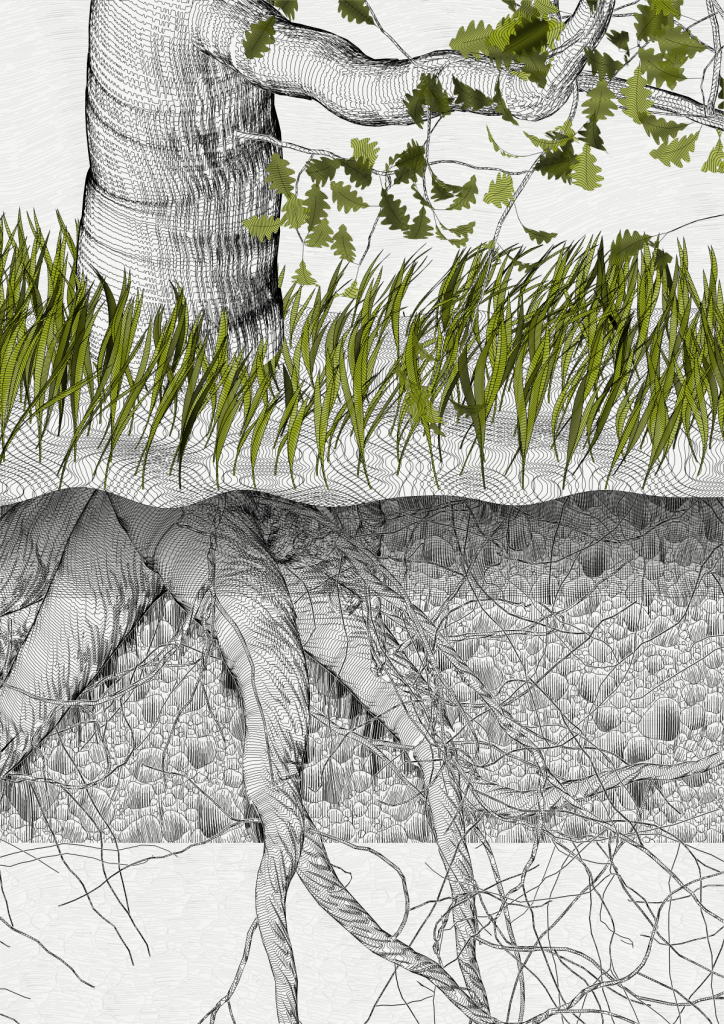

Currently the top-selling artist on the Tezos blockchain, Michaël Zancan—or simply Zancan, as the Frenchman is known online—works with code to create dense, detailed images of trees and plant life. His generative artworks take both physical and digital form, moving between plotter drawings and pixels: a reflection, perhaps, of the fact that he used to work as a programmer by day and an oil painter by night. Since first discovering NFTs in 2021, Zancan has also been a dedicated collector and patron of other artists on the blockchain. “The Green Collection,” an exhibition of works he owns, was staged by Verse Live at Frieze’s No. 9 Cork Street in London earlier this fall.

I’m not sure if you choose to be an artist—perhaps you simply are or you aren’t, and then it is up to you to find a way to live that reality. I was programming well before I started painting. At the age of eight I was already making programs that drew with code, and at fifteen I was making “demos,” animated programs with no other function than to demonstrate a certain visual aesthetic and my technical capabilities in this new medium. I was making generative art, without knowing that it would one day be part of the history of digital art, and of my personal history as an artist.

Still, I always saw painting as the ultimate medium—the only one noble enough to confer the status of artist. Since it was clear that my painting wouldn’t pay off financially, I separated the need to express myself through art from economic needs. I had this almost schizophrenic daily routine: working as a programmer during the day and then painting in the evening, at night, in the early mornings. I always believed that one day I would stop programming to finally devote myself fully to my art.

The reverse, of course, has happened. Like many others, I first heard the acronym “NFT” when Beeple sold Everydays. I knew nothing about finance or crypto, but that same evening I began to immerse myself in learning about this world, taking in so much new information so much I gave myself a headache. I was driven by this immense excitement for what seemed to me to be a technological, social, and artistic revolution. I felt like I was already late, so everything I built afterward was driven by the fear of missing out.

I minted my first NFT, Generative Springtime 01, on Hic Et Nunc after only one month of work, in April 2021. It was a generative drawing of plants, white lines on a black background in a square format. I never put it up for sale, and a few months later I burned it. It took around six months before I started selling NFTs. The first was “The Oak Tree,” a series of fifteen plotter drawings that collectively represent a tree, sold in eighteen parts on Foundation. I have always been inspired by botany and plant life—by the visual effect produced by the repetition of the elementary motif that constitutes a leaf or a blade of glass. In my work I use plants like brushstrokes: they are the basic gesture which, repeated many times, forms the whole. I also think that the pandemic has strengthened my love of nature. During the successive lockdowns my small garden, free and wild, completely changed my experience of isolation. It reminded me of the simple pleasures we can take in the things that surround us.

The day I discovered NFTs, or maybe the day after, I began collecting them. First it was free works on Hic Et Nunc because I didn’t really have the funds to invest—which was frustrating, because this new world was so rich in treasures. I reinjected a good part of my first sales into my collection, like most other artists. It was important for me to understand and to experience the psychology of a collector. What was driving this enthusiasm that pushed people to spend money on digital files? I don’t think you can sell your work as an NFT if you don’t fully subscribe to the principle of attaching monetary value to a digital certificate.

The act of collecting is also a gesture of affiliation and support. It is not always about the work itself: it can be a mark of appreciation of the artist, their values, the causes they champion, their involvement in the community. Sometimes it’s just financial support, which can be so important too.

After a few months, a few hundred NFTs had piled up in my wallet, but there was a real lack of consistency and theme. Even as I came to focus on generative art, it still felt too eclectic. To create some order, I opened an alternative wallet as a kind of catch-all, and I started to restrict my purchases on my main wallet around a color theme. The green collection has become my trademark. On FxHash, I now only have green items.

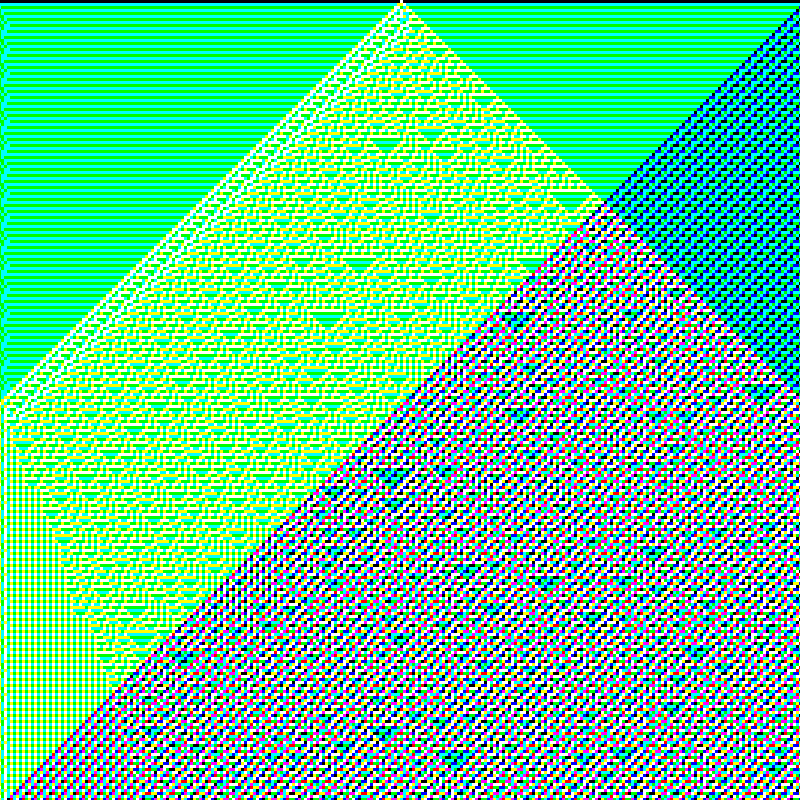

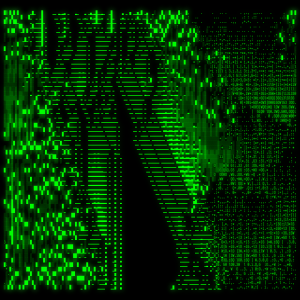

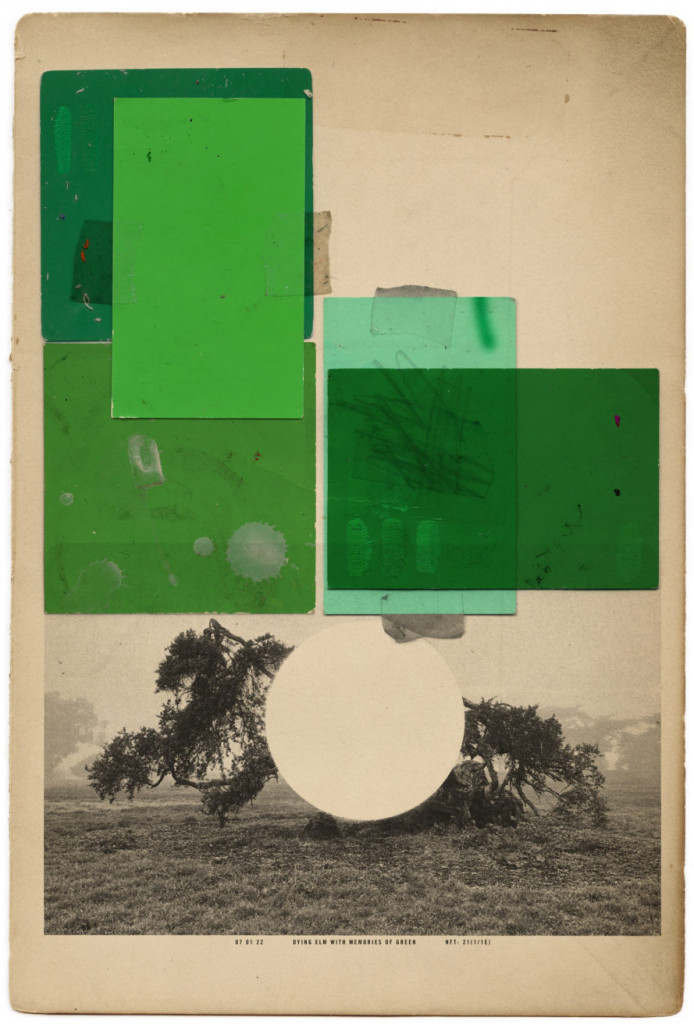

It’s difficult to single out individual works from my collection, because each NFT holds its own meaning for me. I could tell a whole story about every work I’ve collected—drawing together the artistic concept, my relationship with the artist, the resonances with own personal history, the particular circumstances of its acquisition (including maybe its price), and the interactions and or the repercussions in the community. But I would say that RGB (2021) by Ciphrd—who is the creator of FxHash—is one piece that means a lot in relation to my career in the NFT universe. My Smolskull is my favorite PFP: it’s my avatar, the representation of my social and digital “me.” The whole CryptoPixels project, by Rover, is such a funny and spot-on commentary on web3 culture as well as a radical demonstration of the concept of generative art. Finally, 07 01 22 Dying Elm with Memories of Spring (2022) by Gary Edward Blum is a 1/1 NFT that touches me on so many levels—it makes me think about my childhood, the passage of time, my connection to nature, and what inspires me creatively.

Figuring out how to display a collection appropriately takes a long time. Some collectors spend weeks selecting and presenting their works in online galleries, whether in 2D on somewhere like Deca.art or in a 3D metaverse. I just don’t have that time, so my collection is currently accumulating in my wallet. I find I end up forgetting that I own certain works. It was during a chat with Verse’s Mimi Nguyen that we began to dream up the idea for a physical exhibition space with framed prints of all the works in my green collection. It seemed like a totally mad idea, basically a joke, at the time. But then Mimi informed me that an exhibition space was available, and I realized this was a serious proposal. We set about selecting works that would make a coherent and representative display.

Our idea was to talk about the world of NFTs without showing NFTs. We hope that by banning screens, avoiding mention of cryptocurrency, and adhering to traditional display techniques we have created a space where audiences who are usually allergic to digital and crypto can appreciate the art. I have to salute the audacity of the teams involved, who gave their full support to this rather bizarre idea for an exhibition—one in which the artist does not show his own work, where nothing is for sale, and where the organizing theme (the color green) is simply a tactic to bring together people who are working creatively with the tools of their time.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz