The Museum of Modern Art

Collecting digital objects often means fostering conversations across departments and disciplines.

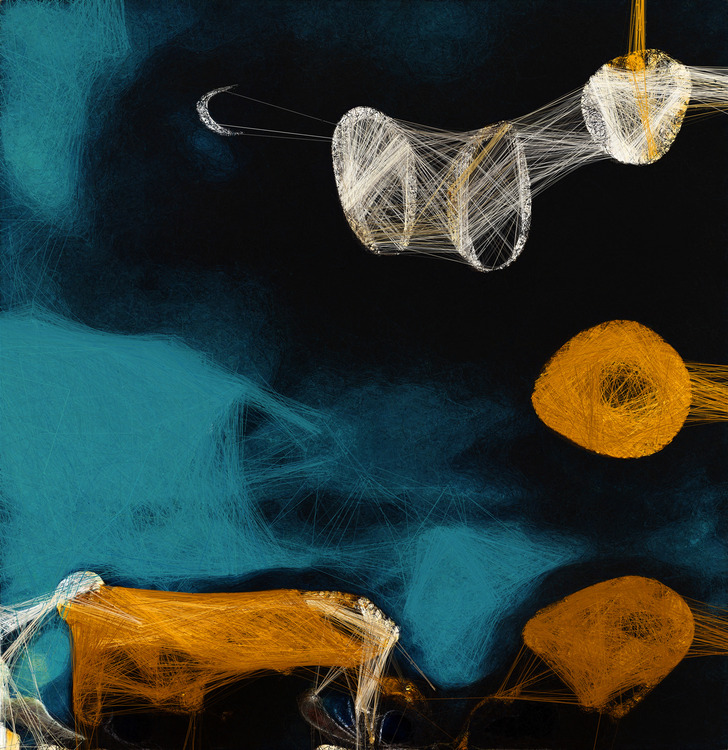

In October, the Museum of Modern Art announced its acquisition of two NFTs: Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised(2022) and Ian Cheng’s 3FACE (2022), signaling a new development in the institution’s long-term engagement with digital objects. This category of work was already robustly represented in the collection by digital video and digitized film, as well as video games and design objects such as the @ sign and the Google Maps pin. Outland editor-in-chief Brian Droitcour spoke with curator Paola Antonelli and collection specialist Paul Galloway from MoMA’s department of architecture and design about the concerns connected to collecting digital objects, as well as the interdepartmental dialogues that such acquisitions often involve. The interdisciplinary spirit adopted by the museum has set the tone for MoMA’s treatment of web3 and its associated applications, which are treated as both avenues for collecting and methods of audience outreach. (The latter approach is exemplified by MoMA Postcard, an interactive art-making game on the blockchain.) Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

BRIAN DROITCOUR Whenever MoMA is in the news for collecting or exhibiting games, people get agitated about whether games can be considered art. The response you usually give in interviews sidesteps that question entirely: MoMA treats games as design. But can games be art, too?

PAOLA ANTONELLI We are curators of design, so we approach reality through the lens of design. Of course, we can think about games as art. But it’s not our job. Until our colleagues in the other departments start collecting them as art we will not go there, as a matter of expertise and territory. The museum needs to present a diversity of angles, because that’s the kind of richness that we can offer its public. When it comes to all that hysteria about video games in MoMA’s collection, we say that they have been collected as design to be precise.

PAUL GALLOWAY Saying video games don’t belong in an art museum is like saying design doesn’t belong in an art museum. We’re not willing to engage in that discussion.

ANTONELLI Or like saying film doesn’t belong in an art museum! People had the same reaction to photography and other new media.

GALLOWAY Design is a field that is so rich. We love it when people invite that discussion. Where do art and design start to cross over? What imperatives do the two share? But we love approaching these questions from the lens of design first, and thinking about the role of the designer in shaping the world around us.

DROITCOUR You’ve spoken of a wishlist of games you want to acquire. What criteria shape that list? Is it a matter of cultural impact? Are the best designed games always the most popular ones?

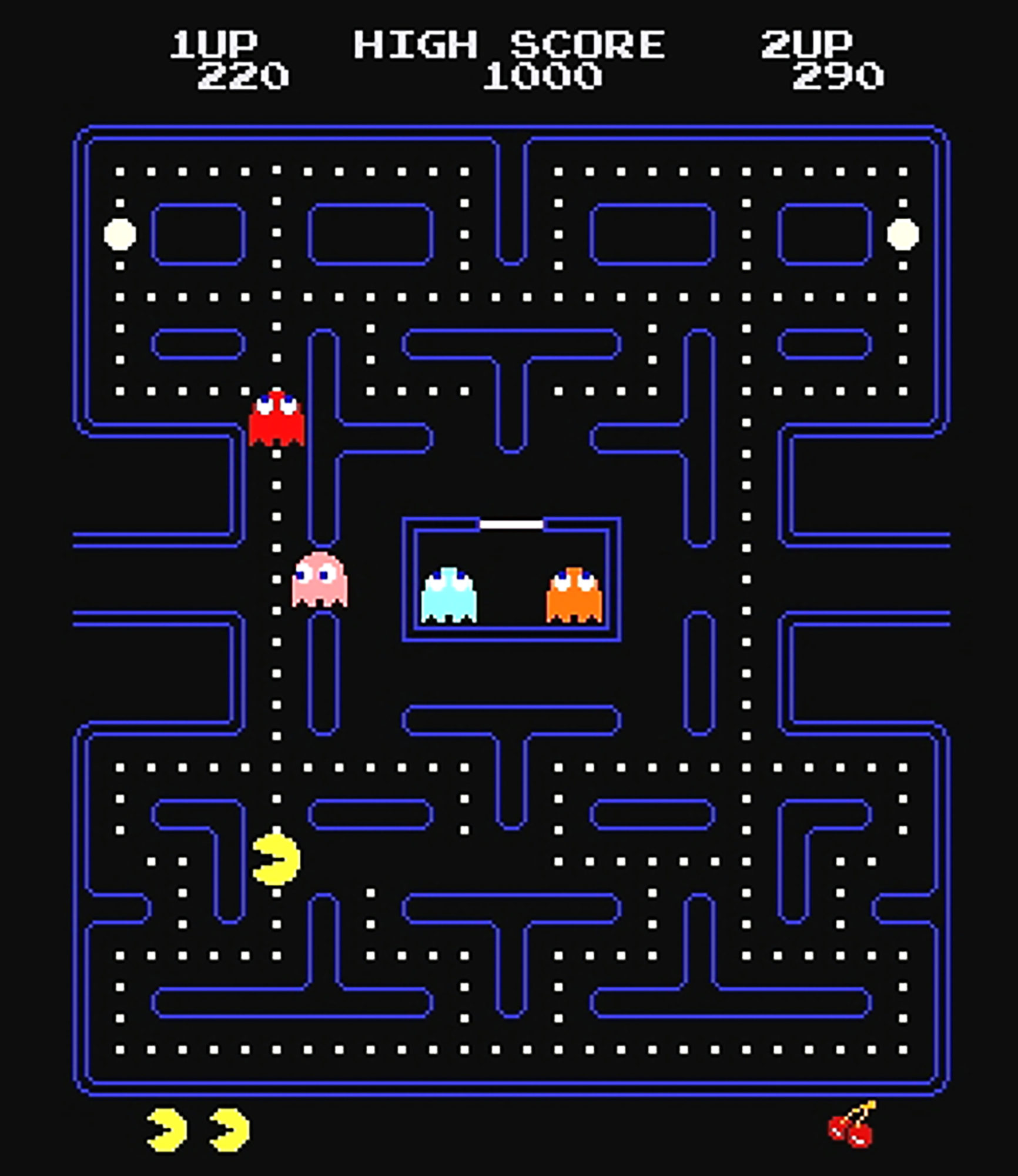

ANTONELLI Popularity is not the most important criterion, though there are games in the collection, like Tetris (1984) and Pac-Man (1980), that are immensely popular. There are indie games, too. I would say that with games we seek out the same things as when we look at, for instance, chairs. We’re looking for popularity, new materials, and new technologies, but we’re also looking for conceptual innovation, a meaningful addition to the world. If this object didn’t exist, would the world miss out? Some of the video games we have collected are pure delight. Some of them push the field of game design forward. Others have become a way for people to express themselves and connect.

GALLOWAY In addition to all those criteria, I think something that we’ve come to understand in the last several years is just how much the player brings. Video games create a mutual relationship. It’s not just an artist putting a painting on the wall and then stepping away. That can be how a video game manifests itself and reveals its beauty and its innovation—howitengages the player by creating an experience that is theirs to shape. Minecraft (2009) is fifteen years old now and it’s still one of the most popular games because it invites the player to contribute their own voice to the world. A great game is not just an expression of the designer’s creative voice; it allows the player to bring something, too.

DROITCOUR What does it mean to bring a game into the collection? What does it look like in MoMA’s storage?

GALLOWAY It depends on the game. Our approach is different from that of other museums with video game collections. We work very directly with the IP holders to create a custom ownership agreement. Sometimes that means we get annotated programming source code. Sometimes we get hardware samples. Namco insisted on giving us a Pac-Man arcade cabinet. But in most cases we don’t have hardware. We have an executable file, whether that’s the original code or an emulation. It exists on a giant server where we keep all of our digital artworks at the museum, from digitized Andy Warhol films to interactive software pieces like Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised (2022).

DROITCOUR I wonder what the file structure of that server looks like.

GALLOWAY The Digital Repository for Museum Collections (DRMC) is a custom database that is constantly running checksums to ensure the files are not corrupted. The appearance of the file structure depends on the work. Pac-Man is a very simple folder with one executable file and another folder with the source code. For the game Portal (2007), we have all the source code in a vast tree of branching data. It’s kind of terrifying to look at.

DROITCOUR You’ve acquired the Google Maps pin. How does that live in the collection? It’s an icon but also exists in an application. Does the software reside in the DRMC in some form?

GALLOWAY Just as we take a chair and remove it from its function—you can’t sit on it once it’s in the collection—we remove the Google Maps pin from the software architecture that supports it and isolate it as an icon. It exists on our server as a vector art file, the same one Google programs into their software.

ANTONELLI The version of the Google Map pin that we acquired is the one that also has the black dot. Whenever you acquire digital objects, you have to decide which version you want. Tetris in our collection is an emulation, redone by Alexey Pajitnov, the original designer. The @ sign is immaterial and abstract. We choose to show it in the American typewriter font, because that’s closest to the 1971 teletype that engineer Ray Tomlinson used to create the email program. For the on/off sign, we created a video that shows how switches for electrical devices went from being labeled with a zero and a one to a single icon in which the two are melded. We always try to show whatever is necessary for the public to understand the object as the design masterpiece that it is.

DROITCOUR On the matter of versions, would you consider having multiple versions of Minecraft or Tetris in the collection, as an approach to redundancy?

GALLOWAY There are examples where we actually have two versions. In the case of Jenova Chen’s flOw (2007), we have both the original Flash game that Chen made for his graduate thesis and the version for the PlayStation, which is much more advanced and atmospheric. But I find it fascinating to see both a sketch and the final form. There’s also the question of when the work came alive. We didn’t get the very first build of EVE Online from 2003 because it was played by a very niche community. We got the version from 2012, the richest moment in its history as a game.

DROITCOUR Paola, I know you’re in MoMA’s web3 working group. How does that compare to other examples of working across disciplinary borders? It sounds like working with new media and new technologies often involves cooperation between departments.

ANTONELLI An acquisition starts with the context where the object was born, but if the format or the medium is something that belongs in another department, we’ll have a conversation. When we acquire an architecture film, for instance, we ask our colleagues in the film department how they feel about it. The Max Headroom Show, a futuristic dystopia broadcast in the UK in 1985–86, was a joint acquisition by the media and performance department and the architecture and design department. With web3 everything is between the cracks. The people in the working group are Michelle Kuo, curator of painting and sculpture; Jan Postma, the chief financial officer; Diana Pan, the chief technology officer; and Madeleine Pierpont, who was hired in a new position as web3 associate to help with all web3 initiatives. Yesterday we had a meeting with our general counsel to discuss the smart contract for the next exhibition that we will have on Feral File. So our approach to web3 gets readjusted every step of the way. We’ve realized it first and foremost in the art—exhibitions and collections—because that’s where we test the new waters.

DROITCOUR The recent acquisitions treat NFTs as art whereas the Postcard project presents them as a kind of interaction design, a way to play a game. Are there other comparable initiatives in the museum’s work at the moment?

ANTONELLI We offered mementos during Anadol’s installation.Visitors couldscan a QR code and download commemorative NFTs into their wallet. If they didn’t have a wallet yet, we’d direct them to open an Autonomy wallet. We wanted to use Anadol’s presence in the museum to teach to as many people as possible both about AI and about the blockchain. It was an opportunity to get them familiar with the ecosystem of web3. That’s another initiative that was quiet, but effective.