One Small Step Backward for Man

Pace’s Discord gives eager crypto speculators a taste of the art world's harsh realities: they go to the moon, you stay here on Earth.

The NFT market may be flagging, but plenty of artists are still entering the fray. On July 28––which would have been the sixty-eighth birthday of former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who died in 2013––Walid Raad released his genesis drop: a series of birthday cakes for global leaders past and present. Chávez, Yasser Arafat, and other polarizing figures are featured alongside out-and-out villains, such as Vladimir Putin. Collectively titled Festival of Gratitude, the cake and editioned “slices” are being auctioned in batches via the new commissioning platform Artwrld, with a significant portion of proceeds going to philanthropic organizations. All the money from the Putin cake primary sales will go to Endaoment’s Support Ukrainian Sovereignty fund; 60 percent of sales of other cakes will benefit further nonprofits selected by Raad, and 5 percent of all resales will be donated, too.

No other artistic medium has ever been so wholly conscripted as a fundraising strategy.

The cakes are multi-tiered monstrosities iced in the colors of national flags, bedecked with bows and flowers and topped with black-and-white cut-out photographs of their imagined recipients. The fact that proceeds from sales of these NFTs will go to charity is central to the meaning of the work. For Nato Thompson, Artwrld’s cofounder, it is Festival of Gratitude’s “greatest irony”: “[A] project that foregrounds the grandiosity and excesses of despots also helps build a different kind of art world that literally pays every time a work is sold and re-sold.” The project is a shrewd foray into NFTs for Raad, making sophisticated use of the medium to build on a large and widely exhibited body of conceptual work that frequently moves between historical fact and fiction to reflect on the effects of war and other traumatic events. It is also the latest example of a trend among big-name artists who have moved from galleries and museums on to the blockchain: the NFT as philanthropy.

For Raad’s peers, incorporating a percentage donation into a smart contract is less a welcome exception than the rule. Artwrld’s artists––the next scheduled drop is by Shirin Neshat in September––are all required to direct a portion of proceeds to nonprofits. Elsewhere, responding to the overturning of Roe vs. Wade in June, Jenny Holzer minted a one-off NFT to raise money for Planned Parenthood and other reproductive health organizations. John Gerrard is donating everything he earns from Petro National, a series of generative NFTs about global oil pollution, to organizations supporting carbon removal and regenerative farming. Although not benefiting an existing charity, a quarter of the sales from Marina Abramović’s NFT series THE HERO 25FPS will be used to fund a program of “hero grants” for web3 projects “that make the world a better, more beautiful place.” Even the rather less idealistic Jeff Koons is giving the proceeds from one of the sales of his Moon Phases NFTs to Médecins Sans Frontières. And crypto-native artists are also getting involved: The latest NFT sale at Christie’s, which included donated works by Beeple, IX Shells and Mad Dog Jones, was held in aid of a nonprofit called the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

Of course, charity art auctions are nothing new. But no other artistic medium has ever been so wholly conscripted as a fundraising strategy. You could argue that this is partly a result of the technological capacities of the NFT smart contract, which can automate the process of distributing pledged funds––not just from primary but also secondary sales. But there is another obvious explanation for the rise of the philanthropic NFT. By dutifully paying their tithes, artists and businesses entering the NFT market can claim to disavow the much-criticized “financialization” of crypto culture––or at least put a positive spin on it. This is not a radical departure from the workings of the mainstream art world: there, too, philanthropic endeavors are used to make the excesses of money and power that flow through the industry more palatable. The ubiquity of charity NFTs pushes things to their logical (or perhaps illogical) extreme: NFTs are all about making money, but this is fine, because the money actually supports a good cause.

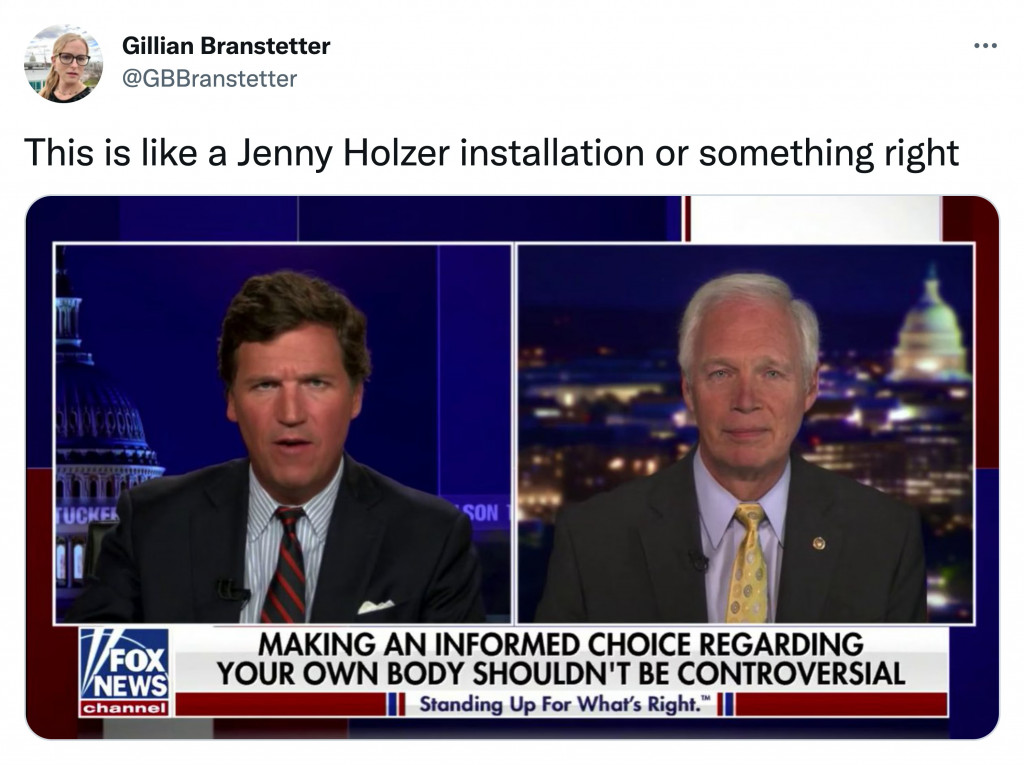

Within this context, it is unsurprising that some artists who are new to NFTs seem to view the technology as little more than a sales mechanism, churning out tokens for pre-existing or extremely basic works. Holzer’s NFT, for instance, is simply a screenshot of someone’s tweet commenting on a still from the Tucker Carlson Show: “This is like a Jenny Holzer installation or something right.” (In the image, the conservative pundit and a guest on his show appear alongside a Fox News chyron that was meant to be about vaccines: “Making an informed choice regarding your own body shouldn’t be controversial.”) The artistic creativity or lack thereof isn’t the point here: Holzer sold the single NFT for 12 ETH, raising the equivalent of 14,500 USD.

By dutifully paying their tithes, artists entering the NFT market can disavow the “financialization” of crypto culture—or at least put a positive spin on it.

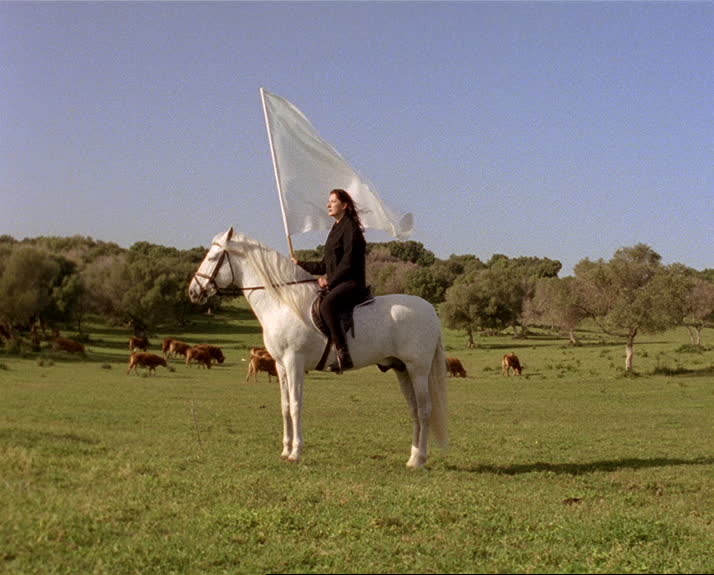

In a similar vein, Abramović’s debut NFT collection recycles 6,500 frames of unused footage from her 2001 video The Hero, which was made as an homage to the artist’s late father, a decorated veteran who fought with Yugoslav partisans against the Nazi occupation. Images of Abramović sitting astride a white horse and waving a white flag can be acquired either as individual frames or as an animated sequence. When explaining why she chose to mint the footage from The Hero in particular, Abramović says she wanted to issue “a global call for new heroes.” She also somewhat unconvincingly describes the NFTs as a “digital performance,” linking their existence on the blockchain to her long-standing interest in ideas of immateriality and audience (or collector) participation. But at the same time Abramović admits that this project is not really about art. The world is at war and on fire, she reminds us, as if we need reminding. Riffing on her Artist’s Life Manifesto of 2011, she has written a Hero Manifesto to inspire applicants for the “hero” grants that sales of the tokens will fund. “Art is not going to save us,” Abramović explains in an op-ed announcing the project. “Today, I am telling people that we have to be adaptable. Right now, we need heroes; less artists but more heroes.”

Art will not save us, that much is true. And there is nothing wrong with wanting your work to help people. But, as I hope others will agree, the value of good art––both on the blockchain and off––goes beyond the funds it can raise, whether for charity or otherwise. So perhaps over time, as artists who have crossed over to NFTs become more familiar with their medium, we will see more projects like Raad’s, which harness the technology to elaborate on ideas or experiences in new and imaginative ways. If they can donate some of the resulting income as well, that’s great. You might call that having one’s cake and eating it, too.

Gabrielle Schwarz is a writer and editor based in London.