Five Views of the Metaverse

What is the metaverse and where is it headed? Five artists and builders share their perspectives.

This past September, Rolling Stone reported on a study’s findings that 95 percent of NFTs are now worthless. The people who had been saying since 2021 that digital pictures have no real value felt vindicated and eagerly touted the study’s results, even though the math behind it was deeply flawed, as crypto-skeptic journalist Molly White explained in a blog post. NFT proponents grimly accepted the findings, too, and only defended their position with weak whataboutism: in the art world as well only a small minority of artists have a secondary market. It was disappointing to see the isomorphism of the NFT and fine art markets accepted as conventional wisdom. After all, artists were drawn to NFTs in 2021 by promises of a qualitatively different system.

Artists were drawn to NFTs in 2021 by promises of a qualitatively different system.

For some NFT artists, the assimilation to art world conventions is a matter of survival. Constant self-promotion on social media drains artists’ energy, as does dealing with speculators who see art as a means to fill their wallets. Collaborating with dealers, agents, and other intermediaries who can take on the responsibility of managing relationships with collectors and audiences begins to look appealing, even if it means promulgating the traditional gallery model. The London-based Verse has been the most consistent standard-bearer for adapting art world tools to the NFT market, hosting pop-exhibitions for each project they commission.

But this year, the most prominent signs of assimilation came through institutional involvement. The Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art each announced substantial NFT acquisitions early in 2023. Both institutions framed these moves as extensions of their historical activity, rather than as a departure into a new field. “The questions being broached by artists through NFTs should be understood as in dialogue with the work of earlier generations of artists,” curators from the Centre Pompidou said in an interview for Outland. LACMA’s acquisition included a gift from collector Cozomo de’ Medici heavy in PFPs and other collectibles, but curator Dhyandra Lawson still emphasized continuity through the lens of the museum’s encyclopedic scope. “Having a more diverse collection also gives us more flexibility in terms of the presentations that these works could appear in,” she said. “You could show certain projects alongside works from our collection of graphic design, or photography, or conceptual art.” In addition to its acquisition, LACMA commissioned new NFT projects in partnership with Cactoid Labs, with Sarah Zucker, William Mapan, Deafbeef, and others making digital works that responded to paintings and photography in the permanent collection. (The initiative echoed a similar project by the Buffalo AKG Museum launched at the end of 2022.)

This focus on continuity makes sense for museums as they endeavor to educate their stakeholders and audiences in new technologies while maintaining a commitment to the histories they are responsible for stewarding. It’s an antidote to the language of NFT advocates who act as if digital art didn’t exist before 2020. But I hope these projects lay the groundwork for a future when this work is collected on terms set by the artists, and when curators understand the field well enough to make sound judgments about the significance of particular works of digital art without relying on links to art that has already been validated by history. Otherwise, they risk treating new practices as identical, or close enough, to older ones, and failing to appreciate their difference.

It seems symptomatic that a year of infrastructural confusion brought projects that reflected on market conditions. The Pompidou collected Jill Magid’s Out-Game Flowers (all works mentioned 2023) shortly after its release by Artwrld. For this NFT collection, the artist assembled bouquets of rare blooms plucked from the code of popular games, highlighting the value that digital objects take on for participants in virtual worlds, where emotional attachments form through narrative and play. Shezad Dawood’s Sea of Redemption, published by Zien, is another example of a work that incorporates digital-native systems of value into its conceptual framework. Dawood invited collectors to “sacrifice” an NFT in order to mint one of his lushly drawn sea creatures, which could then be traded up for rarer ones, as collectors learned about the mythos of the Sea of Redemption universe. “We came up with a way to invite people in a bear market to jettison the shitcoins they bought that are slightly cringe-worthy,” Dawood said. “What else are they going to do with these things? Let’s play with them.”

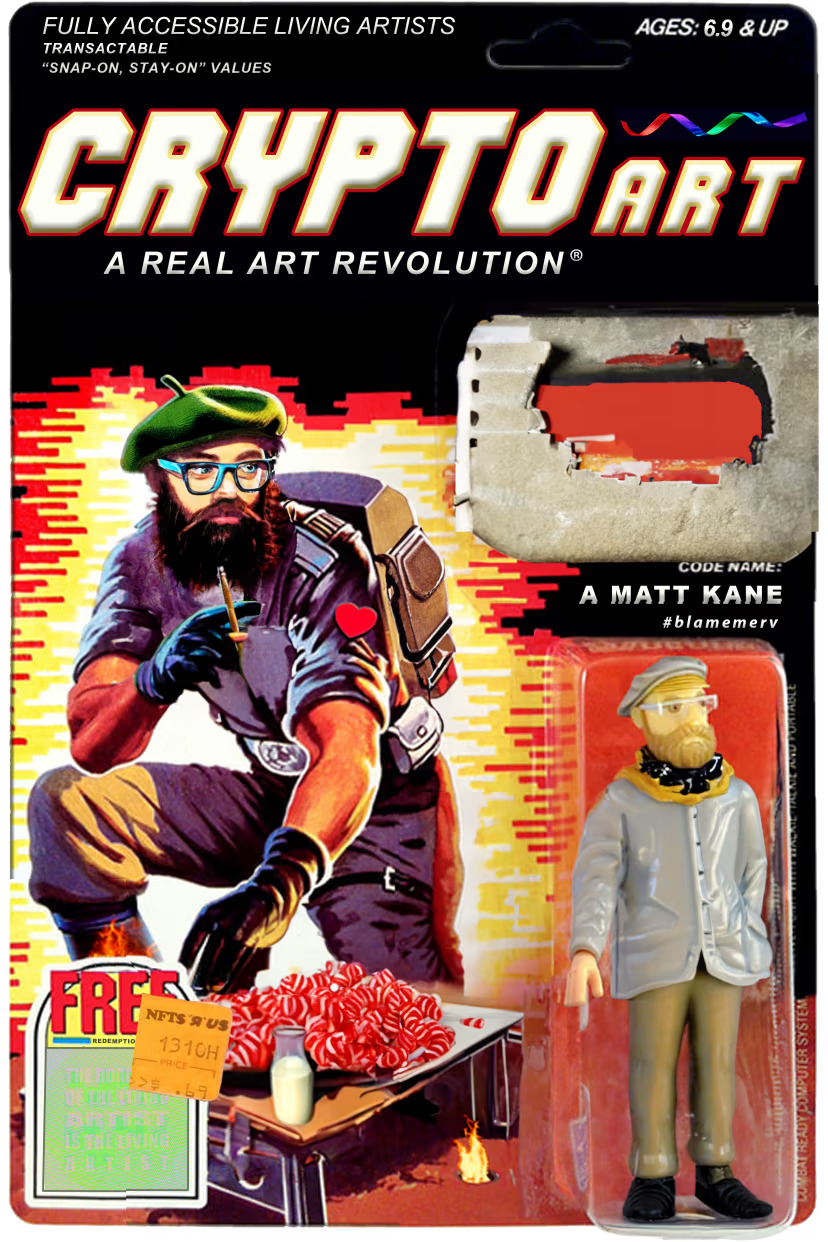

Magid and Dawood both have a history of making work that reflexively thematizes its medium and means of distribution. But other artists who came to prominence thanks to the NFT market also produced projects highlighting its dynamics. To fulfill his agreement to participate in SuperRare’s RarePass program, Matt Kane created Contractual Obligations, a collection of AI-generated images depicting burning bridges and other scenes of fiery destruction. Collectors were confused. They expected the painstakingly coded generative figurations that Kane is known for, and got “low effort” AI art instead. A few weeks later, those who held or acquired Contractual Obligations were given bonus NFTs—more AI-generated images, these ones depicting Matt Kane collectible figurines, with a level of detail and polish correlating to the amount of royalties the collector had paid. Sam Spratt released Monument Game, an expansive landscape of a ruined city, overrun by apes. Those who purchased a tokenized pass could compose observations and inscribe them in the landscape; a group of collectors evaluated the quality of these contributions, and awarded three winners valuable NFTs by Spratt. Kane’s Contractual Obligations was a sardonic sendup of the gamified mechanics of the NFT market and the desires of the collectors active on it, suggesting that the system denigrates the artistic process. But Spratt’s Monument Game is more earnest and hopeful in its incentivization of careful observation and critical writing. Like Out-Game Flowers and Sea of Redemption, these projects are treating the NFT market as a new phenomenon, trying to grasp the new possibilities it brings, good or bad, and say something insightful about them.

Another feature shared by these projects is their large edition sizes, which leverage the digital medium’s flexibility and reproducibility. They incorporate variations in parameters; Sea of Redemption is participatory, and Monument Game offers a chance for creative collaboration. The traditional fine art market and its participants still seem to struggle to comprehend such approaches. The coverage of Sotheby’s auction of the bankrupt crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital’s collection focused on the top lot—Dmitri Cherniak’s “Goose,” aka Ringers #879—neglecting discussion of the generative collection as a whole and how the individual outlier related to it. The scenario reminded me of the auction of Beeple’s Everydays in 2021, when Christie’s stitched together 10,000 drawings into a single, barely legible collage, so that Beeple’s work could be treated as a singular masterpiece, rather than as an iterative practice that fans and collectors had been appreciating via daily updates.

The fine art market has a hard time grasping the collective ownership of artworks, even as an understanding of community-building around large editions has organically formed in the NFT space.

The fine art market has a hard time grasping the collective ownership of artworks, even as an understanding of community-building around large editions has organically formed in the NFT space. A possible bridge between these worlds could be Fora, an initiative launched this fall to make the concerns of preserving digital art more transparent as responsibilities are distributed among artists, collectors, and dealers. Fora’s decentralization is managed without blockchains, but it has implications for the collective stewardship of blockchain-based works, especially ones that have hundreds of iterations and nearly as many collectors. The NFT market won’t become more equitable or attractive to artists without intentional interventions. NFTs and blockchains aren’t solutions in themselves; things like automated royalties, touted as a technological advantage of the market, were implemented and have been maintained through social consensus. If the NFT market is going to be anything more than a pale copy of the art market, repeating all its bottlenecks and inequalities, there need to be intentional efforts to make that happen. The rapid formation and collapse of the NFT market exposed the truth behind all markets for art and other intangible values: that worth is determined through collective consensus. And perhaps the path forward might be found in artworks that thematize innovative ways of building consensus, including play with rarity, interactivity, and collaboration.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.