Historical scale

The restoration of Keith Haring’s 1987 computer drawings proposes a new standard for using the blockchain to store and authenticate historical digital art.

If I were to trace back my fascination for the lecture, it might begin with the weekly Sunday sermon that punctuated my childhood. The sermon, a careful recitation of religious scripture, served as a precursor to the lecture as we know it. Etymologically, lecture comes from the Latin root legere, “to read,” as well as from Greek, where it means “to speak” and “to gather.” In the 1790s, German Professor Johann Gottlieb Fichte departed from the dictation of a “textbook” (religious or otherwise) with a lecture on his own research. And so, as Sophie Seita put it in her 2022 essay on lecture performances, the “authority of the text” segued into the “the authority of the lecturer.”

The lecture in contemporary times usually follows a particular format: a speaker at a lectern, reading a script, clicking through projected slides. What binds these different types of presentation software is “a reliance on performative authority in knowledge production,” as Erica Robles-Anderson and Patrik Svensson outline in their 2016 essay “One Damn Slide After Another.” In my UCLA MFA seminar “Performing Lectures,” I perform the role of a teacher in an institutional context. But when does performance start and when does it end? We modulate between identities now more than ever—and for a lecturer, performing as an authority or an amateur or a character is a strategy for persuasion. The art of public speaking is not about the what but the how. There have been some changes with the advent of digital technologies. Slideshow software like PowerPoint has made the creation of lectures more accessible. Video conferencing relocates the speaker onto a screen. Printed objects become magnified by a projector. AI becomes an interlocutor. AR turns a book into an interface.

The art of public speaking is not about the what but the how.

Nowhere is this more apparent than when public speaking becomes artwork: in the lecture performance. These presentations of information invite disclaimers—think, for instance, of Hito Steyerl’s “This is not Research. This is not Theory. This is not Art,” or Guillaume Désanges’s presentation of “search results that are neither art history, nor science.” The not and nor point to the amateurism of this hybridity. As Seita puts it, “Unlike the lecture, the lecture performance does not profess expertise. It does not need to exhaust a subject. It can dabble and suggest, celebrate passionate amateurism.” The shift from the authority of the text toward the authority of the lecturer centered the focus on the speaker and their authored research. The shift from the authority of the lecturer towards their “passionate amateurism” invited speakers to develop new forms of presenting this authored research by hybridizing genres and breaking conventions.

By breaking down its constituent parts—the lectern, the script, the slides—we see a provisional typology of the lecture performance in these technological times emerge.

The form of the lectern, or podium, suggests its use: a four-foot plinth, for a lecturer at standing height, with a slanted top, for an open book. Gordon Hall draws attention to this convention in Read me that part a-gain, where I disin-herit everybody (2014), a lecture performance about the nebulous lineage of lecture performances. Hall stands behind a plinth on which a projection appears: it is documentation of 21.3 (1964), considered to be one of the first lecture performances, in which Robert Morris lip syncs a reading of art historian Erwin Panofsky’s 1939 lecture “Studies in Iconology.” Usually, when the lecturer stands to the side of the projected slideshow, they are an orator framing the subject. By projecting onto the plinth, Hall transforms the lectern and lecturer into the subject, giving voice to three speakers: himself, Morris, Panofsky.

Other lecture performances forgo the lectern altogether. For a 2022 workshop at Yale School of Art, designer Linda Van Deursen issued a prompt for the design students: “What does it mean for digital objects to exist more than real ones?” In response, M.C. Madrigal performed Phantom Crowds (2022), a critique of the commodification of protest. In front of a green screen, she marched on a treadmill, digitally masked into the crowd alongside hired “protesters” in commercials for Pepsi and Nike to sell soda and athletic gear. Like Hall, Madrigal relocates the focus by merging the projection and the speaker.

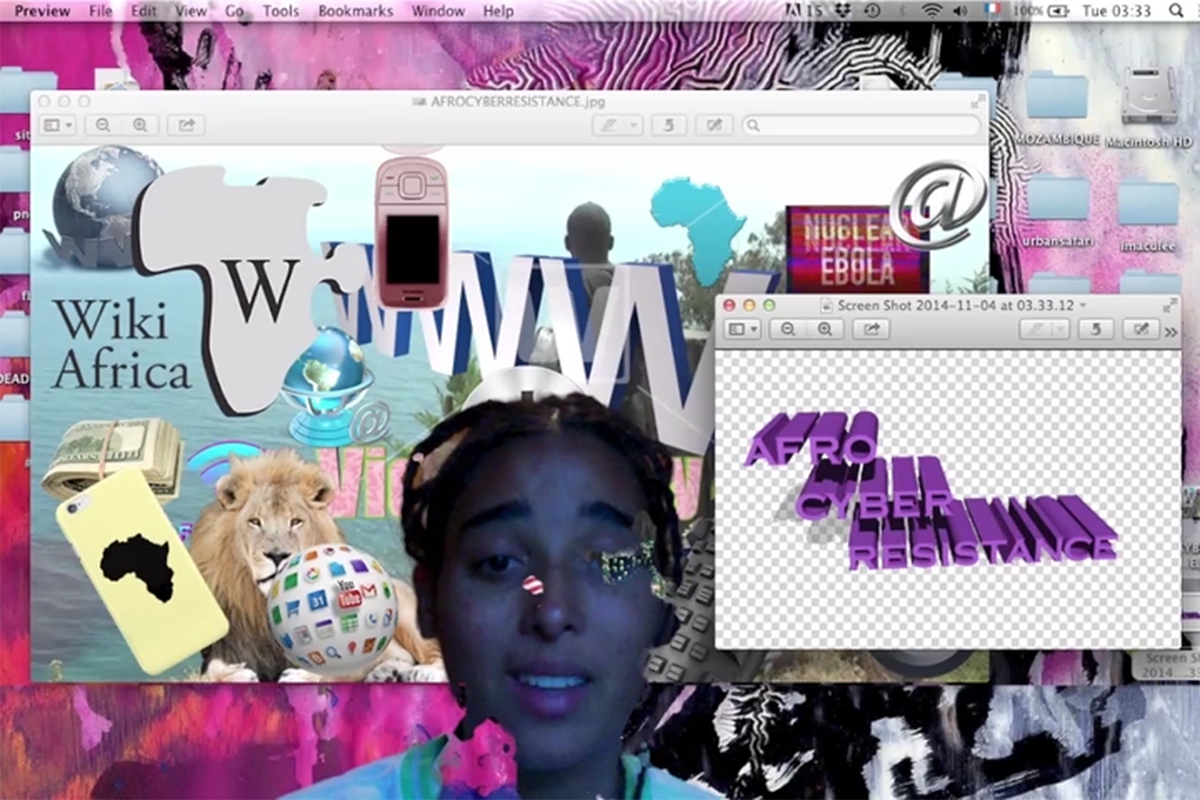

With the rise of Zoom formats, green-screen video art practices also flatten the speaker and their projection into a single frame. In Tabita Rezaire’s AFRO CYBER RESISTANCE (2015), an animated collage of pixelated waving flag gifs, Wikipedia artifacts, and a lion atop a stock beach image is punctuated with rotating lime green text reminiscent of Microsoft WordArt. “AFRO CYBER RESISTANCE” is followed by “SOUTH AFRICAN INTERNET ART.” Rezaire then appears, the virtual background—a pink cloth layered with objects including a bikini-clad Barbie and a desktop computer—cutting holes in her body.

Some lecture performances draw attention to the form of the script, transforming it into a performative object. Emma Rae Bruml scrolls through images of CRT screens, lightpens, and the women programmers who were the first “computers” on a webpage for the lecture-slash-workshop Hand Coding Round Robin (2020). “Inspecting” the browser reveals their lecture notes in the source code as HTML comments, a format I borrowed for a 2021 lecture on cyberfeminism.

Last year I did a book tour for Cyberfeminism Index (2023), a pseudo-encyclopedic tome of online activism and net art. My performative reading was in the style of book designer Irma Boom, who uses an overhead camera to project a live feed of an open book. As I speak, my hands flip through the book, and the printed entries become the script. For the book tour, technology specialist Tommy Martinez helped me conceive of an augmented reality reading to transform the book into an interface, with targets triggering video that appeared atop the printed static image in the book’s projection.

Perhaps the centerpiece of the corporate lecture is the slideshow—Microsoft’s PowerPoint (initially released as “Presenter” in 1987), Apple’s Keynote (2003), and Google’s Slides (2007). While some lecture performances continue to use slideshows, they shift the focus away from a series of static visual references or keywords that progress in a linear format. Others decenter the slideshow, using it for metadata, or remove it altogether, focusing on liveness.

Perhaps the centerpiece of the corporate lecture is the slideshow.

In her theatrical performance Prometheus Firebringer (2023), Annie Dorsen reads a textual assemblage of excerpts that becomes a coherent questioning of how AI language generation works—by training models on existing data. “You’ll see that I’m using other people’s words,” she states as the citation “‘Pakeha Perspectives on the Treaty’, New Zealand Planning Council” flashes on the slides behind her. Throughout the performance, Dorsen’s words are accompanied by their respective sources. This minimal display of text is a flashing footnote to her words, thereby changing the status of footnotes to a key aspect of the script, rather than a buried bibliography. (Other elements of the performance are generated by GPT 3.5.)

Anisha Baid’s Sally’s Helper (2023) also explores footnotes as a subject and form. In this performance, Baid critically fabulates the story of Sally, the secretary at Xerox PARC who was the “model user” of the first GUI, only to be mentioned without a last name in the footnotes of a case study. Baid sits at a laptop, gingerly typing as Sally; each computer key is mapped to a piano key on the neighboring extra-baby grand piano, and lines like “a chair wears a skirt and twirls” become a song. The secretary and a pianist—both perform the writings of others, but only one is seen as artistry.

In each of these lecture performances, the knowledge transfer of lectures merges with the novel presentation of performance. These works recognize and play on performative authority and in doing so they reveal the conventions of a lecture, breaking down its constituent parts: the lectern, the script, the slides. When public speaking becomes art, the digital and physical apparatus of the performance becomes visible.

Mindy Seu is a designer, educator, and researcher based in Los Angeles and New York.